Italy / France

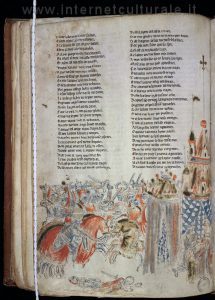

Manuscript: First half of the fourteenth century CE

Anonymous

Geste Francor

Bovo d’Antona, Karleto, Uggieri il danese, Berta ai piedi grandi, Berta e Milone, Orlandino, Macario (Beuve d’Hampton, Karleto, Ogier le danois, Berte aux grands pieds, Berta et Milon, Rolandin, Macaire)

This manuscript from northern Italy without its initial pages contains the first version of a literary family saga from the Italian peninsula. It incorporates the history of the Carolingians, briefly including Pepin (Charlemagne’s father), then at length Charlemagne’s purported half-siblings, and finally his son Louis. It incorporates chansons de geste from the French tradition—Beuve d’Hampton, Karleto, Ogier le danois, Macaire—to which it adds the story of the conception, birth, and youth of Roland, Charles’s nephew, famous from the Chanson de Roland (Song of Roland).

Until the mid-twentieth century, it was treated as a series of separate poems mauled linguistically and in plot by inadequate, illiterate northern Italian street poets. Since the 1980s, however, Henning Krauss’s sociological analysis concerning Italian attitudes toward the northern European feudal system (Epica feudale e pubblico borghese) and renewed interest in the mixed Franco-Italian linguistic forms of the text have led to greater appreciation for the authorial reworking of traditional material, with serious consideration of its humorous scenes and its relation to other European texts. Since this site is in English, my introduction does not touch on the work’s linguistic complexities, but RIALFrI (manuscript) and Berta ai piedi grandi (text) give an idea of the nature of its language, called Franco-Italian or, historically, Franco-Venetian.

The manuscript begins in medias res since an unknown number of pages are missing, with Bovo (see Bevis of Hampton on this site) trying to regain his city, here called Antona, which Dodo, a Maganzese (a person from Maganza, that is, Mainz in Germany) holds through having married Bovo’s mother after she had Bovo’s father killed. Bovo has returned to the area to survey possibilities for retaking the city. He stays with one of his father’s men, Siginbaldo, whose wife prepares a bath and spies on Bovo, discovering his identity through a birthmark. Siginbaldo and other allies assist in retaking Antona.

Bovo’s story breaks at this point to tell, in the segment known as Berta ai piedi grandi, of Pepin taking a wife, Berta, known as Bertha Big-Foot in English, the daughter of the king of Hungary. She is married by proxy through ambassadors, and on the way to Paris, the group stays with the Maganzesi. There Berta befriends the daughter of Belençer. The girl could be Berta’s twin, and Berta persuades the girl to accompany her. When they arrive in Paris, Berta is too tired and afraid to sleep with the king, and asks her Maganzese twin (never named) to do so. The girl likes being queen and arranges to have Berta taken to the woods and killed. But Berta talks her way out of it, and stays in the woods with a forester and his daughters. One day the king goes hunting in the woods near the forester’s home. There he stays overnight and sees Berta. He asks that she sleep with him and she agrees. Meanwhile, back in Hungary, Berta’s mother is disturbed at the lack of news and comes to check up on her daughter. The Hungarian queen unmasks the imposter and goes seeking her daughter, whom they find in the woods with Charles, her son by the king. The false queen is burned, but her three children stay at court to cause trouble.

The poem then returns to Bovo d’Antona, where Pepin, the king of France, has been bribed to assist the Maganzese Dodo in retaking Antona from Bovo. King Pepin and his men are defeated and imprisoned, but Bovo’s wife persuades her husband to release the king, who then agrees to support Bovo forever against the Maganzesi.

The tale then turns to Charles in the segment usually called Karleto. He has grown into adolescence at the Parisian court. His half-Maganzese half-brothers think they should hold the kingdom. With the encouragement of their Maganzese relatives, they poison Pepin and Berta. They also relegate Charles to the kitchens (for echoes of this sort of behavior, see Renoart in the Guillaume tales). Charles must flee when threatened by his siblings, and ends up in Spain where he helps the pagan king fight off invaders, while the king’s daughter falls in love with him and converts to Christianity in order to marry him. The couple must then flee because Charles’s brothers-in-law plot against them. Charles and his wife go to Rome where the pope, also a Maganzese, seeks Charles’s death. With the assistance of his Hungarian relatives, Charles survives and replaces the pope. He then returns to Paris where he executes his half-brothers and places his half-sister, young Berta or Bertella, under his wife’s control.

The plot continues somewhat later, in the story of Ogier le danois. Outside Rome, in one of the frequent sieges of the city by pagans in which the French are called to help, Ogier the Dane saves the French troops by winning in an individual combat of two pagans versus two Christians. He not only defeats his own pagan opponent, but also saves Charlot, Charles’s son, thereby earning the youth’s bitter enmity. Charlot had insisted in participating in the combat against his father’s wishes, and was thus proved wrong publicly. The Ogier story, too, is divided, with the second half after Berta e Milone, the story of Roland’s conception and birth.

In the segment usually called Berta e Milone, court life in Paris allows Berta, Charles’s half-sister, to make the acquaintance of Milon of Clermont. They fall in love, and though Charles had plans for her to marry for political purposes, Berta finds herself pregnant. The lovers flee, and a furious Charles places a price on their heads. In Imola, Berta delivers her son, whom they bring up in the woods near Sutri.

The following segment, the second half of the Ogier tale, takes the knight on an impossible mission to Marmora, in northern Italy. Although many critics suggest that this episode criticizes the thirteenth-century ruler Ezzelino da Romano, more recently Mascitelli argues that it may be rather against Cangrande della Scala, who echoed Ezzelino’s practices in the early fourteenth century, the era of the manuscript. In any case, Ogier takes the city and installs a ruler friendly to France. He returns home to find that his son has been killed by Charlot, and he kills Charlot in response. Charles condemns Ogier, but Roland saves him. When a pagan army attacks, only Ogier can win, but he demands satisfaction from the king before defeating the pagan champion. The army marches back to Paris through the Italian peninsula.

The following segment is designated Orlandino or Rolandin, “young Roland.” When Charles is returning from the battle in Rome, he holds open court at Sutri, which is just north of Rome on pilgrimage routes. Roland lives nearby and runs with a gang of youths. The ever-hungry Roland presents himself twice at court, eating a lot and taking more home for his parents. Charles, very impressed, would like the young man to fight for him. Naimes, ever the “fixer,” manages to follow Roland and finds his mother and father in the woods. Naimes arranges for Charles to forgive his sister and for Roland to participate in the court.

The final segment of this lengthy poem, usually called Macario or Macaire, takes place long after Roland’s death in the battle of Roncevaux. It tells of the Maganzese Macario who seeks to avenge himself on Charles by trying to seduce his wife. After the wife’s rude refusal, Macario bribes a dwarf to sneak into bed with her while Charles is at church. When Charles returns together with Macario and others, he finds them in bed—she, asleep, completely unaware of her company. Charles condemns them, but his wife is pregnant and therefore sent instead into the woods with a young knight to accompany her out of the realm. Macario follows, defeats the young knight whose dog, however, returns to court to attack Macario. The wife meanwhile gets away accompanied by a woodsman. The king and court, having become suspicious of the dog’s constant attacks on Macario, arrange a single combat of the dog against him. Macario loses, confesses, and is executed. Charles then seeks his wife who, in the meantime, had given birth to their child Louis in the woods and been rescued by the king of Hungary. She had then returned to Constantinople, which was ruled by her father. He marches on Paris to fight Charles because of his unjust accusations. Ogier (who knows that the queen is alive and present) fights her woodsman protector, resulting in the Dane’s (planned) defeat and the return of the queen.

Certain concerns reappear in episodes of the poem deriving from original pieces now woven together: among these are unfairly appropriated land; women’s fickleness and infidelity; warriors’ (including the king’s) lust; and, related to all of these, the legitimacy of heirs. The constant rivalry between two families, the Maganzesi and the Carolingians, form the backdrop to the entire poem. That rivalry, in addition to the above-mentioned concerns, continue in varying proportions through Italian adaptations of Carolingian material into cantari, which are poems in ottava rima, frequently about a single character, then in Andrea da Barberino’s prose Reali di Francia (end of the fourteenth-early fifteenth century, a best-seller through the nineteenth century), and further to Matteo Maria Boiardo’s Orlando Innamorato, Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, and beyond.

Note: This is a very brief introduction to the 17,067 line poem. For more complete and detailed summaries, please see the introduction to the Morgan edition; for a discussion of the specific critical issues concerning Charlemagne in the poem, please see my co-authored chapter in Charlemagne in Italy (“The First Franco-Italian Vernacular Textual Witnesses of the Charlemagne Epic Tradition in the Italian Peninsula: Hybrid Forms”).

Leslie Zarker Morgan

Loyola University Maryland

Works Cited

Les Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (ARLIMA), director Laurent Brun, département de français de l’Université d’Ottawa. <last consulted 20 November 2022>.

ʻLa Geste Francor’: Chansons de geste of Ms. Marc. Fr. XIII (=256): Edition with glossary, introduction and notes, ed. Leslie Zarker Morgan. 2 vols. Tempe, AZ: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 2009.

Krauss, Henning Epica feudale e pubblico borghese. Per la storia poetica di Carlomagno in Italia, trans. F. Brugnolo et al. Padua: Liviana, 1980.

Mascitelli, Cesare. La ʻGeste Francor’ nel cod. marc. V13: Stile, tradizione, lingua. Strasbourg: Éditions de linguistique et de philologie, 2020.

Morgan, Leslie Zarker, and Claudia Boscolo. “The First Franco-Italian Vernacular Textual Witnesses of the Charlemagne Epic Tradition in the Italian Peninsula: Hybrid Forms.” In Charlemagne in Italy, edited by J. E. Everson. Charlemagne: A European Icon, general editors Marianne Ailes and Philip E. Bennett. Bristol Studies in Medieval Cultures Series. Martlesham, Suffolk, UK: DS Brewer, 2023. 26-73.

Repertorio Informatizzato Antica Letteratura Franco-Italiana (RIALFrI), director Francesca Gambino, Dipartimento di Studi Linguistici e Letterari, Università degli Studi di Padovavia Elisabetta Vendramini 13, 35137 PADOVA. <last consulted 20 November 2022>.

Resources

Manuscript

Venice, Italy. Biblioteca San Marco Fr. Z. 13 (=256) [Geste Francor]. The manuscript is available online on RIALFrI.

Editions

La ‘Geste Francor’ di Venezia. Edizione integrale del Codice XIII del Fondo francese della Marciana, ed. Aldo Rosellini. Brescia: La Scuola, 1986.

ʻLa Geste Francor’: Chansons de geste of Ms. Marc. Fr. XIII (=256): Edition with glossary, introduction and notes, ed. Leslie Zarker Morgan. 2 vols. Tempe, AZ: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 2009.

Translations

Lazzeri, G. “Orlandino.” In L’influsso francese in Italia nel Medioevo, Corso di filologia romanza, 1968-69, ed. R. M. Ruggieri. Rome: DeSanctis, n.d., pp. 233-52. (segments, into Italian)

Morgan, Leslie Zarker. “Berta and Milone” and “Rolandin”, translations and introduction to Franco-Italian, ORB (On-Line Reference Book for Medieval Studies).1996; updated 2006. (into English)

Criticism

Holtus, Günter, and Peter Wunderli. Les Épopées Romanes. Dir. Rita Lejeune, Jeanne Wathelet-Willem, Henning Krauss. Tome 1 / 2, Fascicule 10 de Grundriss der romanischen Literaturen des Mittelalters (GRLM). Franco-italien et épopée franco-italienne. Heidelberg: Winter, 2005.

Krauss, Henning Epica feudale e pubblico borghese. Per la storia poetica di Carlomagno in Italia, trans. F. Brugnolo et al., Padua: Liviana, 1980.

Mascitelli, Cesare. La ʻGeste Francor’ nel cod. marc. V13: Stile, tradizione, lingua. Strasbourg: Éditions de linguistique et de philologie, 2020.

Morgan, Leslie Zarker and Claudia Boscolo. “The First Franco-Italian Vernacular Textual Witnesses of the Charlemagne Epic Tradition in the Italian Peninsula: Hybrid Forms.” In Charlemagne in Italy, edited by J. E. Everson. Charlemagne: A European Icon, general editors Marianne Ailes and Philip E. Bennett. Bristol Studies in Medieval Cultures Series. Martlesham, Suffolk, UK: DS Brewer, 2023. 26-73.

There are earlier editions of the individual segments of text, and extensive bibliographies. See ARLIMA and RIALFrI for more references.

The above bibliography was supplied by Leslie Zarker Morgan (Loyola University Maryland).