Iran

Composed: ca. 977-1010 CE

Abolqasem Ferdowsi,

Shahnameh

The monumental poem of the Persian poet Ferdowsi, the Shahnameh or Book of Kings, which was completed by this poet in the year 1010 CE, is a massive retelling of the lives and times of 50 kings of Iran. The reigns of these kings, called shāh-s in Persian, extend from the mythical past all the way to the historical moment when Iran, once a mighty empire, finally collapsed. The first king of Iran, then, was the first king of the world, who was the shāh at the time of creation, while last king was the last of the shāh-s, Yazdgerd III, whose death in 651 BCE marks the end of the Iranian Empire, then ruled by the Sasanian Dynasty. This dynasty of kings, upholders of the religion of Zoroaster, was militarily and politically eliminated in the wake of a series of events that culminated in what is known to historians as the Islamic Conquest of Iran, also known as the Arab Conquest.

Though the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi was created in the Islamic Iran of the early part of eleventh century, both its overall narrative time frame and even its orientation are pre-Islamic, reflecting a Zoroastrian worldview. Thus the historical contexts for the reception of this poetry, over time, need to be studied not only in terms of prevailing Islamic worldviews, both Sunni and Shica, but also in terms of older mentalities still preserved in the poetic tradition inherited by Ferdowsi.

The monumentality of the Shahnameh, which has been noted here from the start, is most evident when we consider its sheer size. In the surviving medieval manuscript tradition of the Shahnameh, there is one version that stands out in this regard. It stems from a recension, commissioned by the Timurid prince Bāysonghor in 1426 CE, that contained around 58,000 verses (in Persian, beyt-s, which are distichs or couplets). Other versions contained fewer verses, but most versions in any case contained far more verses than are accepted in some modern editions, since some experts today will question the authenticity of many of the verses contained in the manuscript tradition. For example, the Moscow edition of the Shahnameh (edited by Bertels and colleagues, 1960-1971) contains 48,617 verses (to which are added in an appendix 1,486 further verses, deemed probably spurious), by contrast with the less critical Calcutta edition (edited by Macan 1829), containing 55,204 verses. In any case, the monumentality of the Shahnameh as a poetic achievement is undeniable. The number of its pages runs up to 996 in the single most accessible and by far most successful translation of this poem into English, by Dick Davis, elegantly published in a single volume by Penguin Books in 2016.

An essential question, for those who read the Shahnameh in translation, is this: how to read this exquisite work of Persian verbal art, masterfully translated, as world literature? Here we need to look beyond the title of this poem. Unlike what its traditional title might suggest, this “book of ‘kings” is also an “epic of heroes” (Davidson 2013a). As “epic,” it is comparable with such other epics of world literature as the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa of India or the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey of the ancient Greeks—or even the Gilgamesh narrative originating from the far more ancient Sumerians. In the light of such comparisons, the best approach for appreciating the Shahnameh as translated into English would be to highlight not so much the kings in this poetry but rather its heroes—again, as in the case of the term “epic”, I use the term “heroes” with a view to compare the Shahnameh with the best-known epics of world literature (Davidson 2013b).

Three Persian heroes stand out as most readily fitting for comparison: Rostam, Esfandiyar, and Siyavash. These three heroes as paragons of Persian poetry match comparable heroes in other epics of world literature, but I emphasize here their importance in the Shahnameh itself. Rostam is by far the most prominent of all the heroes of the Shahnameh. He is a warrior without equal, defeating countless enemies not only as a general of armies but also as a sole combatant, ever-ready to fight to the death anyone who challenges him. As a lone fighter, he also vanquishes dragons, demons, and witches. His deeds of valor as a fighter can lead to tragic results, however, and the prime example is the story about his mortal combat with the hero Sohrab, whom Rostam kills without yet realizing that his victim is his own son, abandoned since childhood.

The prowess of the hero Rostam as a fighter is linked to his sense of duty towards the kings of Iran, since his self-avowed mission in life is to defend the imperial authority. In this case as well, however, the hero’s deeds of valor as a fighter can lead to tragic results. A sad example involves the second of the three heroes highlighted here. He is Esfandiyar, who is not only a hero like Rostam but also a potential king of all Iran. Although Rostam is a sworn defender of such kingship, he is forced by his code of honor to respond to the challenge of prince Esfandiyar to engage in a fight to the death. The winner of the fight is Rostam, who becomes in this case a sadly reluctant killer of royalty. The third of the three heroes highlighted here is Siyavash, who becomes a martyr for his own sense of honor by staying true to promises made.

One characteristic that is shared by all three of these heroes is that each one of them feels deeply involved in the politics of kingship. Thus they are not only heroes of epic but also agents of royal destiny. Even if, despite this agency of theirs, they are more often unsuccessful than successful in their involvement with kings, these heroes must nevertheless remain involved with royalty, since the stories of these heroes are embedded in the stories about the kings in this Book of Kings.

Olga M. Davidson

Boston University

Works Cited

Bertels, Y. E., et al., eds. 1960–1971. Ferdowsi: Shāhnāma I–IX. Moscow.

Davidson, O. M. 2013a. Poet and Hero in the Persian Book of Kings. 3rd ed. Ilex Foundation Series 11. Cambridge, MA (2nd ed. 2006, Costa Mesa, CA; 1st ed. 1994, Ithaca, NY).

Davidson, O. M. 2013b. Comparative Literature and Classical Persian Poetics. 2nd ed. Ilex Foundation Series 12. Cambridge, MA (1st ed. 2000, Costa Mesa CA).

Davis, D., trans. 2016. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Expanded edition. New York.

Macan, T., ed. 1829. The Shah Namah. Calcutta.

Resources

Editions in translation:

Ferdowsi, Abolqasem. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Trans. Dick Davis. Penguin, 2006. [the most complete English-language edition]

—. The Legend of Seyavash. Trans. Dick Davis. Mage Publishers, 2004. [a single episode]

Critical studies:

Dabashi, Hamid. The Shahnameh: The Persian Epic as World Literature. Columbia University Press, 2019.

Davidson, Olga M. “The Burden of Mortality: Alexander and the Dead in Persian Epic and Beyond.” In Epic and History. Eds. David Konstan and Kurt A. Baaflaub. Wiley Blackwell, 2014. 212-222.

—. “Persian/Iranian Epic.” In A Companion to Ancient Epic. Ed. John Miles Foley. Wiley Blackwell, 2009. (1st ed. 2005). 264-276.

—. Poet and Hero in the Persian Book of Kings. 3rd ed. Ilex Foundation Series 11, 2013. (2nd ed. 2006; 1st ed. 1994).

—. “The Text of Ferdowsi’s Shâhnâma and the Burden of the Past.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 118 (1998): 63-68.

Davidson, Olga M., and Marianna Shreve Simpson, eds. Ferdowsi’s Shahnama: Millennial Perspectives. Ilex Foundation, 2013.

Hillenbrand, Robert, ed. Shahnama: The Visual Language of the Persian Book of Kings. Routledge, 2004.

Further reading supplied by Atefeh Akbari (Barnard College):

Shahnameh Visual Guide

Women in the Shahnameh video series

Zahra Faridany-Akhavan

The Tahmasb Shahnameh Illustrations

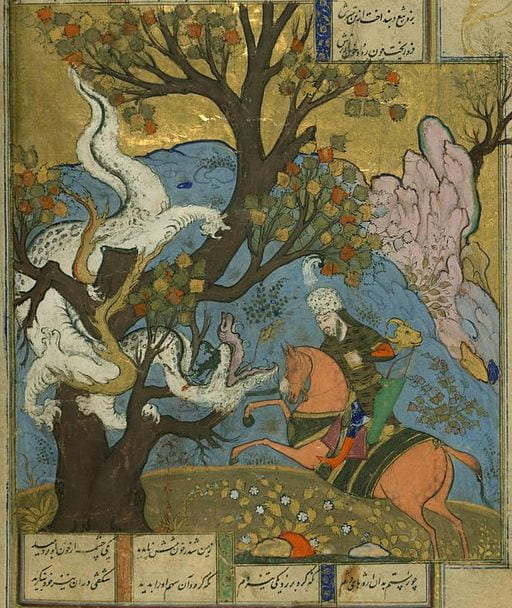

Images depicting Seyavash:

“Siyavush Plays Polo before Afrasiyab“, Folio 180v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp

Painting attributed to Qasim ibn ‘Ali, ca. 1525–30, Tabriz, Iran.

(Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

“The Fire Ordeal of Seyavash,” from a Shahnameh

Herat, Afghanistan, ca. 1430

(Portland Museum of Art)

“The Fire Ordeal of Seyavash,” from a Shahnameh

Unknown Iranian artist, ca. 1630 or later, India.

(Portland Museum of Art)

“Siyavash Is Pulled from His Bed and Killed,” from a Shahnama manuscript

Master of the Jainesque Shahnama, ca. 1425–50

(Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Please scroll to the bottom for additional images from the episode of Seyavash.

A range of episodes from illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh:

Shahnama Project: A comprehensive collection of manuscripts of The Shahnama.

Curated video tour of Library of Congress exhibit entitled “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book” (the Shahnameh and selected illustrated manuscripts are discussed 6:21-12:57)

Three illustrated manuscripts from the Library of Congress exhibit “A Thousand Years of the Persian Book” (2014).

Exhibit of illustrated Shahnameh manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam Museum:

video presentation

introduction

gallery

The Wedding Celebration of Zal and Rudaba (Harvard Art Museums)

The Simurgh Returning Zal to his Father (Seattle Art Museum)

Illustrations at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rustam Captures Rakhsh

Rudaba’s Maids Return to the Palace

Zal Expounds the Mysteries of the Magi

Birth of Zal

“Master of the Jainesque Shahnama“ (31 results)

Digital collage prints by Iranian-American artist and filmmaker Hamid Rahmanian, including a map of the poem’s geographical extension, for a new translated edition of the Shahnameh (2013).

Hamid Rahmanian’s video presentation of his illustrations, explaining his technique in creating a collage from thousands of manuscripts, lithographs, and miniatures from the 13th to 19th centuries.

“Shahnameh for a New Generation: The Epic of the Persian Kings” (video interview with Rahmanian, with examples of his illustrations)

Exhibit by Iranian artist Saeed Khazaei in Tehran (2018).

Additional resources in lecture notes by Soroor Ghanimati, “The Hero Rostam in Persian and Central Asian Art,” UC Berkeley (2018).

Poupak Azimpour Tabrizi (University of Tehran) has shared links to a wealth of images dealing with the legend of Seyavash:

Seyavash images 1

Seyavash images 2

Seyavash images 3

Seyavash images 4

Seyavash images 5

Seyavash images 6

Seyavash images 7

The Cambridge Shahnama Centre for Persian Studies

Friends of Shahnameh Facebook group. A public group based in Manchester, UK. Includes posts in English as well as announcements of events in both Farsi and English.

Shahnameh for Kids. Illustrated picture books retelling ancient Persian myths and legends.

Feathers of Fire: A Persian Epic is a visually breathtaking cinematic shadow play for all ages, created and directed by Hamid Rahmanian, a 2014 Guggenheim fellowship-winning filmmaker/visual artist. The play unfolds an action-packed magical tale of the Shahnameh’s star-crossed lovers Zaul and Rudabeh, who triumph at the end against all odds.

Q&A with Hamid Rahmanian, in conversation with Olga M. Davidson (Boston University) and John Bell (Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, University of Connecticut). Followed an online screening of Feathers of Fire hosted by the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry.

Story of Gordafarid, documentary by Hadi Afarideh about the first female Iranian storyteller of the Shahnameh (2012):

Female Iranian epic storyteller Gordafarid presents “The Story of (female warrior) Gurdafarid and Sohrab” (no English subtitles). The background shows art in the exhibition “In the Field of Empty Days: The Intersection of Past and Present in Iranian Art” (2018).

Female Iranian storyteller Fahimeh Barotchi recounts a series of episodes involving Rostam and Esfandiar.

Highlights from the tragic opera Rostam and Sohrab by composer Loris Tjeknavorian (Tehran 2000).

Dance interpretation of story of Gurdafarid and Sohrab.

Introducing Ferdowsi, recitation by Mohammadhasan Sadeghi (no English subtitles).

The following questions are geared toward a discussion of the “Legend of Seyavash” from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh in the context of the upper-level undergraduate course Nobility and Civility: East and West (Columbia University global core).* A syllabus of the course can be found here.

Abolqasem Ferdowsi (c. 940-1020), Shahnameh, translated by Dick Davis. Penguin Classics, 2016. “The Legend of Seyavash,” pp. 215-280.

Like the ancient Indian Ramayana and Mahabharata, Ferdowsi’s early eleventh-century Iranian Shahnameh is an immensely popular and enduring epic right up to the present day. The legend of Seyavash is one of many episodes dealing with conflictual father/son relationships in royal families. How does Seyavash compare to Arjuna and Rama as a noble figure? How are his dilemmas different?

In what ways do the two opposing states, Iran and Turan, act as mirror images of each other?

What is the first important mixing (or crossing of the border) between these two states? Consider also the successive moments of mixing and crossing due to various causes (war, self-imposed exile, marriage), including the subsequent actions of Seyavash’s son Khosrow (summarized in the translator’s afterword).

What ideas on statecraft emerge through the actions and statements of the characters? Are there any commonalities with the Arthasastra or the Ramayana?

What view of human nature emerges based on the actions of Ferdowsi’s characters?

Sometimes the author comments directly as narrator on the state of the world, especially suffering caused by human injustice. We might discuss the following statement (as well as other similar and dissimilar ones) in light of previous texts this semester (e.g., Analects, Daodejing, Bhagavad Gita, Dhammapada):

“I search to right and left, on every side, / And see no sense, no head or tail, in how / This earth goes – since one man does evil deeds / And luck is his, the world is like his slave. / While one who never acts unrighteously / Withers away in wretchedness. But keep / Your distance from the sorrow of this world / And do not let it grieve your heart and soul.”

Can we gauge the relative responsibility of Fate and human agency when considering the multiple causes of the story’s development? Is there any way Seyavash could have changed the course of events? Is he at all to blame for what happens to him?

To situate this epic story geographically:

1) the legendary land of Turan is associated with the large territory on Iran’s northeastern border (modern Turkmenistan and beyond). Also, the Iran of the Shahnameh extends beyond the current nation of Iran.

2) The battle between Iran and Turn in the early part of the narrative takes place at Balkh (now in northern Afghanistan). In Plutarch’s Life of Alexander you would have seen it as Bactria (it’s where Alexander marries Roxana following his victory).

3) What other countries beyond Iran and Turan are mentioned and in what context?

There are many works of art featuring Seyavash, including illustrations in manuscripts. Determine which figure is Seyavash in the following:

Siyavush Plays Polo before Afrasiyab

Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University)

“Teaching the legend of Seyavash in Columbia University’s Global Core curriculum”

Zoom presentation hosted by the Friends of Shahnameh on the Commemoration Day of Ferdowsi 2020.

*This two-semester course was designed through the Faculty Workshops for a Multi-Cultural Sequence in the Core Curriculum (Heyman Center for the Humanities, 2002-2009), directed by the late Wm. Theodore de Bary, at Columbia University.