West Africa (the Sudanese empire of Old Mali)

Oral tradition: c. 13th century CE

Written summaries (Arabic): before 1890

Translations (French, German): 1890-1898

First line-by-line transcription: 1967

Epic of Sun-Jata*

Sun-Jata (Son-Jara, Sundiata) was the founder of the Empire of Mande, the second largest multi-ethnic, medieval empire in West Africa (c1230-c1600s). Today, his memory is celebrated by an orally transmitted epic, sung by professional bards. These bards are casted, which means that they alone are allowed to perform the epic in public.

The Epic of Sun-jata is performed in a wide range of countries in West Africa, principally in Mali, Guinea, the Gambia, and Senegal, but can also be found in various poetic and prosaic forms in Ghana, Burkino Faso, and the Ivory Coast.

The structure of oral epics reveals a set of primary poetic, narrative, heroic, and legendary traits, as well as secondary traits such as great length, multi-functionality, cultural traditional characteristics, and multi-generic traits. African oral epics act in a social manner similar to the Bible or the Koran in other areas of the world. Proper collection of a living epic, like Sun-jata, can add to our understanding of all epics, even those limited to the text.

The belief that political power is held not by force alone but by control of the occult accounts for the themes which describe the paternal and maternal inheritances of Son-Jara. In this context, the Islamic concept of barakah, “grace,” can be considered the Moslem equivalent of local Mande nyama, “occult power.” From his father, descendant of immigrants from Mecca, Son-Jara inherits barakah; from his mother, descendant of the Buffalo-Woman of Du, he inherits nyama. With both of these occult sources, he will seek to gain the political power of his destiny. Son-Jara’s major battles against his adversaries are described in the epic not as great conflicts of weaponry, but rather as battles of sorcery. But the inheritance of barakah and the personal acquiring of nyama are still not enough to provide Son-Jara with the power he needs to fulfill his destiny. Before Sumamuru can be defeated on the field of war, Son-Jara must first learn the secret of his occult power and make counter-sacrifices to eliminate its efficiency.

The heroic life of Son-Jara, the greatest of all Mandekan heroes, can be viewed as a series of transformations in the pursuit of power with which he is able to fulfill his destiny, according to Mandekan worldview. Beginning as a cripple, the limping hero goes through several transformations, each gaining him more power than the last, and finally he becomes the most powerful hero ever to have lived.

*Search for the Manden Culture Hero under the following spellings: Sunjata, Sunjatta, Sun-Jata, Soundiata, Sundiata, Sundjata, Sondyara, Son-Jara, and Nare Magan Konate.

John William Johnson

Indiana University

The latter two paragraphs are excerpted from the introduction to The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, oral performance by Fadigi Sisòkò, transcribed and translated by John William Johnson et al. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana UP, 1992), p. 9.

Resources

Authentic Texts

[Original, complete texts transcribed from the bards’ own performances, some with translations]

Condé, Djanka Tassey (text), David C. Conrad (recorded, edited and translated), Sunjata: A West African Epic of the Mande Peoples (Indianapolis: Hacket Pub., 2004) [English only]

Diabate, Lansine (text), Jan Jansen, Esger Duiintjer, Boubacar Tamboura (trans., ed.), L’Épopée de Sunjara (Leiden, Netherlands: Onderzoeschool vor Aziatische, Afrikaanse en Amerindische Studiën [Research School of Asian, African, and American Studies], Leiden University, 1995) [original Mandenkan language, plus French translation]

——— Magan Sunjara: Manden Buruji, l”Histoire de Manden (Bamako, Mali: Editions Jamana, 1997) [Mali publication of above; original Mandenkan language, plus French translation]

Diabaté, Massa Makan, L’Augle et l’Épervier, ou La Geste de Sunjata (Paris: Edition Pierre Jean Oswald, 1975) [French only; text by Kele Mònsòn Diabaté]

Duintjer, Esger, Jan Jansen, Toumani Sidibe & Boubacar Tamboura, Makan Sunjata – Manden buruju, l’histoire du Mande (Bamako, Mali: Éditions Jamana, 1997) [Bamanakan adaptation of Jansen 1995; see below]

Innes, Gordon (introduction, translation, annotation), Bamba Suso (text), Bana Kanute (text), Dembo Kanute (text), Sunjata: Three Mandinka Versions (London: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1974) [includes original language]

———, with assistance of Bakari Sidibe, Sunjata: Gambian Versions of the Mande Epic by Bamba Suso and Banna Kanute (London: Penguin Books, 1999) [edited, introduction & notes by Lucy Durán & Graham Furniss]

Jansen, Jan (trans., ed.), Les Secrets du Manding: Les récits du sanctuaire Kamabolon de Kangaba (Mali) (Leiden, Netherlands: Research School Centrum voor Niet-Westerse Studies, 2002)

Jansen, Jan, Esger Duintjer & Boubacar Tamboura (trans., ed.), L’épopée de Sunjata d’après Lansine Diabate de Kéla (Mali) (Leiden, Netherlands: Research School Centrum voor Niet-Westerse Studies, 1995) [original Maninkakan language, plus French translation]

Jansen, Jan, Esgar Duintijer & Boubacar Tamboura, Sunjata: Het beroemdsta epos van Afrika zoals verteld in Kela (Rijswijk, Netherlands: Bibliotheca Africana, 1998) [Dutch translation of Jansen, 1995]

Johnson, John William, The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1986) [English translation only. Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò]

———, The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1992) [English translation only. Student edition paperback. Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò]

———, Son-Jara: The Mande Epic, New Edition (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2003) ) [English translation with original Bamana language. Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò]

———, Son-Jara: The Mande Epic: Performance by Jeli Fa-Digi Sisòkò Two CDs (Bloomington: Indiana University Press & AuralLabs, 2004)

Kamissoko, Wa (text), (trans. Youssouf Tata Cisse), L’Empire du Mali (Paris: Fondation SCOA pour la Recherche Scientifique en Afrique Noire, 1975) [includes Bamana text and French translation]

———, La Grande Geste du Mali (Paris: Kartala, 1988) [essentially same as above]

———, Soundyata: Le Gloire du Mali (Paris: Kartala, 1988) [same as above, vol. 2]

Kouyaté, Mamadou, L’Épopée de Sunjata (Saint-Denis, France: Éditions Publibook, 2016)

Moser, Rex E. Foregrounding in the Sunjata: The Mande Epic, (Bloomington, Indiana: Department of Linguistics, PhD Dissertation, 1974) [includes a text of the epic by sung by the bard Kele Monson Jabate, recorded by Charles S. Bird in 1968.

Sako, Abdulaye (text), Stephen P.D. Bulman, Valentin F. Vydrine (ed., trans.), The Epic of Sumanguru Kante (Leiden, Netherlands, Brill, 2017) [includes original Bamana text; recordings available online]

Sisòkò, Fadigi (text), John William Johnson, et al (analytical study & translation), The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1986 [first edition]

———, The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1992 [student edition]

———, Son-Jara: The Mande Epic, Mandenkan/English Edition with Notes and Commentary, 3rd ed. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2003 [includes original language; CD or performance available]

Sisòkò, Magan (text), John William Johnson, et al (collection, transcription, translation, annotation), The Epic of Sun-Jata According to Magan Sisòkò, (Bloomington, Indiana: Folklore Publications Group, vol. 5, 1979) [collected, translated & annotated]

Transcribed, Translated Episodes from the Epic of Sunjata

[Original, episodes transcribed from several bard’s performances]

Conrad, David, (intro, ed.), Epic Ancestors of the Sunjata Era (Madison: African Studies Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1999)

Sanassy Kouyaté, “Village Issues and Mande Ancestors” (Trans, David Conrad, Emmanuel Yemoson, Yaya Dialo, (1996), Seku Camara (1997)

Fayala Koutae, “Kamajan and Islam” & “Janjon” (trans. David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1994), Emmanuel Yemoson, Djibrila Doumbouya (1996)

More Kouyate, “Ancestors, Sorcery, and Power” (trans. David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1991)

Mamadi Diabate, “Fakoli” (trans, David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1991)

Mamadi Konde, “Sogolon and Sunjata” (trans, David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1992)

Mamadi Condé, “Fakoli and Sumaworo” (trans. David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1991)

Denba Kouyaté, Sunjata” (trans David Conrad, Djobba Kamara, Lansana Magasouba (1992)

Reconstructed Texts in Prose

[Texts rewritten in prose instead of the original poetry]

Camara, Laye, Le Maître de la Parole (Kouma Lafôlô Kouma) (Paris: Librairie Plon, 1978) [based on a text of the bard Babu Condé]

Camara, Laye, James Kirkup (trans.), The Guardian of the Word (Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1980) [English translation of above; republished in 1984 by Vintage/Random House, New York]

Diabate, Lansine, Jan Jansen, Esgar Duintijer, & Boubacar Tamboura (translators), Het Sunjata-Epos (Den Haag, Netherlands: Gegevens Koninklijke Biblioteek, 1994)

Diabété, Massa Makan, Kala Jata (Bamako: Éditions Populaires, 1970)

Frobenius, Leo, “An Historical Poem (The Mandes or Mandingoes),” chapter 21 in vol. II of his: The Voice of Africa, Being an Account of the Travels of the German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the Years 1910-1912 (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1968): 449-66 [First published in 1913]

———, “Die Sunjattalengende der Malinke,” chapter 16 in vol. V of his: Atlantis: Volksmärchen und Volksdichtungen Africas: Dichten und Denken in Sudan (Jena: Eugen Dieterichs, 1925): 303-331

———, “Ergänzungen zur Sunjattalengende der Malinke,” chapter 16 in vol. V of his: Atlantis: Volksmärchen und Volksdichtungen Africas: Dichten und Denken in Sudan (Jena: Eugen Dieterichs, 1925): 331-43

Kouyaté, Mamadou, reconstructed by D.T. Niane, Soundiata, or l’Épopée Mandingue (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1960) [although reconstructed, Niane is the scholar that introduced the Epis of Sunjata to Western readers; republished in ]

———, Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali reconstructed by D.T. Niane, translated by G.D. Pickett, Soundiata: An Epic of Old Mali (London: Longman, 1965) [republished several times with new covers. The latest in 2006]

Zeltner, Franz de, “La Légende de Soundiata,” and “Suite à la Légende de Soundiata,” in his Contes du Sénégal et du Niger (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1913): 1-36, 37-45

Reconstructed and Composite Texts in Prose

[Several texts rewritten in prose instead of the original poetry and combined from performances of several bards]

Ba, Adam Konaré, Sunjata: Le Fondateur de l’Empire du Mali (Libreville, Gabon: Les Nouvelles Éditions Africaines LION, 1983)

Conrad, David C. (ed., trans., intro.), Sunjata: A New Prose Version (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub, 2016) [Conrad collected from the bards Djobba Kamara and Lansana Magassouba]

Diabate, Lansine (text), Jan Jansen, Esger Duiintjer, Boubacar Tamboura (trans., ed.), Het Sunjata-Epos, (Leiden, Netherlands: Onderzoeschool vor Aziatische, Afrikaanse en Amerindische Studiën [Research School of Asian, African, and American Studies], Leiden University, 1994) [reconstruction of French text above in Dutch]

Sidibe, Bakari K., Sunjata (Banjul, The Gambia: Old National Library, 1980) [composite prose from four sources originally collected by Gordon Innes, op cit.]

Texts for Classroom Use

Belcher, Stephen, Epic Traditions of Africa, “Sunjata and the Traditions of the Manden,” in his (Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 1999): 89-114 [A study of the epic with a composite prose narrative of the complete epic from several bard’s performances]

Caws. Mary Ann & Christopher Prendergast, “Maninka People, Mali,” from Harper Collins World Reader: Antiquity to the Early Modern World (New York: Harper Collins, 1994): 1068-77 [Introduction with an excerpt from The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Notes, translation, and new introduction by John William Johnson, Indiana University Press, 1992]

Evans, Walter, ed., “Introduction to the Epic of Son-Jara,” from The Augusta College Humanities Handbook, 7th edition (Needham Heights, Massachusetts, Simon & Schuster Custom Publishing for Augusta College, Augusta, Georgia, 1996): 129-38 [Introduction with an excerpt from The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Notes, translation, and new introduction by John William Johnson, Indiana University Press, 1992]

Mack, Maynard, gen. ed., “Africa: The Mali Epic of Son-Jara,” The Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces, expanded edition in one volume (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1997): 1430-72 [Introduction with an excerpt from The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Notes, translation, and new introduction by John William Johnson, Indiana University Press, 1992]

Jansen, Jan, “The Dynamics of ‘Sunjata’: Reports About the Past in Kela (Mali), in Jaruch G. Oosten Text and Tales: Studies in Oral Tradition (Leiden, Netherlands: 1994): 107-15.

Johnson, John William, Thomas A. Hale, & Stephen Belcher, “The Epic of Son-Jara narrated by Fa-Digi Sisòkò, “from Oral Epics from Africa: Vibrant Voices from a Vast Continent (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1997): 11-22 [A study of several epics from Africa, including excerpts , plus an excerpt from The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, Text by Fa-Digi Sisòkò, Notes, translation, and new introduction by John William Johnson, Indiana University Press, 1992

Traoré, “Relevance and Significance of the Sunjata Epic,” in Jaruch G. Oosten, Text and Tales: Studies in Oral Tradition (Leiden, Netherlands: 1994): 79-94.

Von Hoven, Ed, and Jarich Oosten, “The Mother-Son and Brother-Sister Relationships in the Sunjata Epic,” in Jaruch G. OostenText and Tales: Studies in Oral Tradition (Leiden, Netherlands: 1994): 95-106.

Reconstructed Children’s Books

[Simplified texts retold by the authors]

Baby Professor, When Sundiata Keita Built the Mali Empire: Ancient History Illustrated Grade 4; Children’s Ancient History) Newark, Delaware: Speedy Publishing, 2017) [Reconstructed, soft-bound children’s book]

Bertold, Roland (text), & Gregorio Prestopino (illustrator), Sundiata: The Epic of the Lion King, Retold (New York: Thomas Crowell, 1970) ) [Reconstructed, hard-bound children’s book]

Fontes, Justine, Ron Fontes (text), Sandy Carruthers (art work), Sunjata: Warrior King of Mali (Minneapolis: Graphic Universe, 2008)) [reconstructed as a graphic novel]

Eisner, Will, Sundiata: A Legend of Africa (New York: Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine, 2002) [reconstructed as a graphic novel]

Wisniewski, David, Sundiata: Lion King of Mali (New York: Clarion Books, 1992) [Reconstructed, hard-bound children’s book]

Stage Drama

Diakité-Kaba. Issiaka, Soundjata, Le Lion: Le Jour où la Parole Fut Libérée / Sunjata, The Lion: The Day When the Spoken Word was Set Free (Théâtre Africain / African Theater) (Denver, Colorado: Outskirts Press, Inc., 2010) [Bilingual French-English Edition]

The above bibliography was compiled by John William Johnson (Indiana University).

Further reading:

Washington Post article on the Met Exhibit.

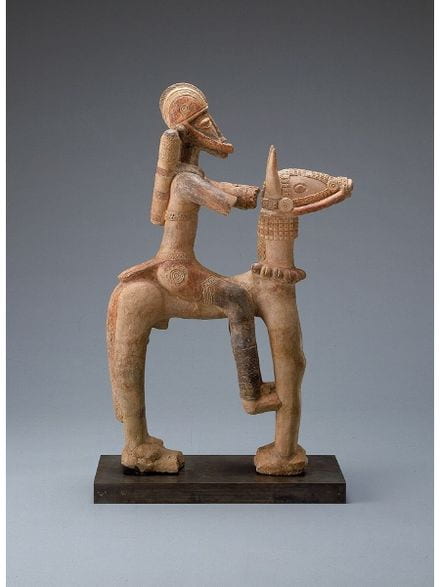

Figure: Pair of Balafon Players.

Empires of Western Sudan, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Portrait of Sogolon, Mother of Sundiata, High Museum of Art.

The Founders Project by Stephen Hamilton: 1) the project; 2) Dashawn Borden as Sundiata Keita.

An excerpt of the epic of Son-Jara recited by Fa-Digi Sisòkò (1968):

Open access musical recordings of Sunjata, reading list for the Sundiata, University of Birmingham:

The Sunjata Story – Glimpse of a Mande Epic. Narrative in English by Lasana Diabate—Song mode by Hawa Kassé Diabaté—accompaniment on balaphone by Fodé Lassana Diabaté

Sidiki Diabaté & Djelimady Sissoko – The Sunjata Epic.

Recorded reading of the Sunjata, Smithsonian.

Article about Malian balafon player, Balla Kouyate.

Rokia Traoré’s “Dream Mandé-Djata project (narrative retellings of the Sundiata in French and English)

Sidiki Diabaté & Ensemble – The Sunjata Epic.

Mandékalou – Soundiata Live @ the Cité de la Musique.

Keita (film retelling first ⅓ of the Sundiata).

Salif Keita – Soundiata. [Music—poetry—no motion]

Mande Hunters: Past and Present. Documentary by Chérif Keita. Includes a clip from a stage production of the Epic of Sun-Jata:

The Meaningful African Poem, The Epic of Sundiata:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: How Griots Tell Legendary Epics through Stories and Songs in West Africa

World Lit I Epic of Sunjata I and II: Michael Mohr:

Sundiata Keita – An Epic of The Mali Empire (Humanity Archive):

Sundiata Keita (Lion King). Seshemet Community Council Academy:

Who was the real Lion King? (StoryDive):

The above links were suggested, among many available, by John William Johnson (Indiana University).

Podcasts/Playlists:

-

- Sunjata Playlist, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

AN EXEGESIS OF THE PLOT OF THE EPIC OF SON-JARA

by John William Johnson (Indiana University)

The following exegesis corresponds to the version published in The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition, oral performance by Fadigi Sisòkò, transcribed and translated by John William Johnson et al. (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana UP, 1992)

Indigenous audiences who listen to an oral performance of the Epic of Son-Jara (Sun-Jata) share the same worldview and culture with a Mande bard, who does not need to explain passages which may be obscure to the foreign reader of the printed text. Readers will need introductions to the text and explanatory notes to guide them through the plot. Therefore, the section entitled Annotations to the Text” (pp. 102-140) of the book, together with the crib notes below, will help guide the reader through the plot.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1 to 159)

God’s covenant with humanity begins with His greatest creation in heaven: Hadama (Adam), held above the angels. The angel Iblis objects to Adam’s status, claiming angels are greater than humans, so God expels Iblis from heaven transforming him into the shaitan (Satan). Adam’s genealogy is given.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 160 to 261)

God’s covenant is passed to Adam’s grandson Nuhun (Noah), who passes it on to his three sons Haman (Ham), Caman (Shem), and Yafisu (Japheth), who populate the earth after the flood. Haman is the forefather of all southern peoples (Hamitic-Black); Caman, of all middle peoples (Semitic-White); and Yafisu, of all northern peoples (Eurasian-Yellow).

Fa-Digi jumps ahead from Caman over several generations to Islam’s Prophet Muḥammad, bypassing Abraham, from whom Muḥammad inherits God’s covenant of baraqah. The progeny of Haman is covered next, with the birth of the Prophet’s companion Jòn Bilal, and the founding of the great Medieval West African empires beginning with Wagadugu, (historically Gāna), where the families of the Manden, the second great empire, originate, ending with the Kònatè mansa (monarch) Fata Magan Kònatè, Sun-Jata’s father. Thus, baraqah is passed from Adam, to Noah to Abraham to Ishmael to Muḥammad to Bilal, and thus to Sun-Jata.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 262 to 288)

Fa-Digi describes Saman Berete and the origin of her family. She will become the first wife of Mansa Fata Magan Kònatè She gives birth to his first-born son Mansa Dankaran Tuman.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 289 to 324)

Fa-Digi describes the origin of the Tarawere Family, descendants of Hussein, (5) the grandson of the Prophet and twin of Hassan. Two of Hussein’s sons, Tukuru and Gasine, begat Dan Mansa Wulandin and Dan Mansa Wulanba, who inherit baraqah, and become hunters with strong nyama. Their combined powers will help them do battle with the Buffalo-Woman (Du Kamisa).

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 354 to 422)

Fa-Digi describes the origin of Sun-Jata’s maternal family, the Kòndè, beginning with Mansa Magan Jata, whose aunt Du Kamisa performs mixed Moslem and Mande birth rites: shaving his birth hair on the eighth day of life when he is formally given a name and putting the hair, umbilical cord and swaddling clothes in a calabash. She secretly buries the calabash for occult reasons, because she is a powerful sorceress. The child grows up and makes a terrible mistake by not inviting his aunt to a divination ceremony to insure the success of his reign. She confronts the Kòndè mansa and he is enraged. She takes revenge with the nyama of the items in the buried calabash.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 423 to 748)

The purpose of the long episode of the Buffalo-Woman is to insure that Sun-Jata will eventually inherit powerful nyama from his Kòndè family. A weak old crone in the daytime, she shapeshifts into a dangerous water buffalo at night and ravages the land so disastrously that the king is forced to seek help from hunters known for their powers of nyama. They conjure to increase their nyama, but fail to overcome the Buffalo-Woman, causing them to use stronger occult means. In the end, Du Kamisa reveals her secrets to the hunters, and they overcome her. The bard sings praises of hunters who live in the bush away from the safety of towns.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 749 to 770)

This passage exemplifies the context in which a bard frequently finds himself. He describes the origin of the Jebaatè family of bards, which seems out of place in the plot, until he explains in the last line that a Jebaatè bard, who has caught his attention, is present at this performance.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 771 to 946)

Back to the plot, the hunters return to court with evidence of their kill, the horns, hooves and tail of the buffalo. The tail is considered especially powerful, as it is the seat of nyama in all animals. Informed of the Buffalo-Woman’s death, the mansa summons hunters to come forth. Some hunters try to claim they killed the buffalo, but the Tarawere hunters produce the trophies which prove their success. The Kondè mansa offers them half his kingdom and any fair maiden for a wife. But Du Kamisa has instructed them to reject all offers but one, who will be identified by a cat who walking between their legs when the right maiden is presented. To the crowd’s horror, they choose the king’s ugly daughter Sugulun, who is covered with warts but who has inherited nyama from her aunt. Laughter is quickly silenced as one of the hunters cures all her warts with his knife blade. All three then depart for the Manden.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 947 to 1043)

Along the way, the hunters attempt consummation with Sugulun, the elder first, then the younger, but she resists with her occult power. Meanwhile a djinn [6] appears to Mansa Fata Magan Kònatè, the king in his capital Nyani and tells him hunters will come to the Manden with Sugulun, whom he must secure for a wife, because she will bear a powerful son to rule the Manden. Fata Magan trades his daughter and a sacred token inherited from Bilal for Sugulun. The hunters agree, for they fear the nyama of the ugly maiden. Thus the handsomest man in the Manden takes the ugliest woman for his second wife, and both his wives become pregnant.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1044 to 1159)

Both wives of Fata Magan give birth on the same day, Saman Berete’s son first, Sugulun’s son second. But Sugulun’s son is announced to the king first, thus beginning co-wife rivalry between the two women. The result is that Saman Berete summons her holy man (mori) to place a hoax on Sun-Jata, causing him to be crippled. She then summons her omen master (kinyè-mansa) to read divination.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1160 to 1177)

Sugulun has a personal djinn in her service. Tanimunari transports the cripple Sun-Jata to Mecca for the ḥajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca required of every Moslem. Sun-Jata is thus further strengthened with baraqah he will need to overcome his lameness.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1178 to 1254)

These lines describe the omens Saman Berete’s omen master conjures concerning the future of her son Dankaran Tuman and Sun-Jata, each time in Sun-Jata’s favor, so the results are kept secret.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1255 to 1535)

This passage describes the humiliation Sugulun endures because Sun-Jata is crippled. She begs village women for baobab leaves (7) to cook for sauce, but they refuse and mock her, saying her crippled son should fetch them for her. Sun-Jata asks her to cook a different leaf full of nyama and to commission blacksmiths to forge an iron staff with which he tries to stand up. Twice he fails, so he asks his mother to cut a branch from the custard-apple tree to support his weight and he rises up. The weak branch, full of nyama, succeeds where the iron staff failed. Sugulun and other women sing songs of praise to Sun-Jata, who revenges his mother’s humiliation by uprooting and transplanting a huge baobab to his mother’s compound. Now women must beg Sugulun for leaves.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1536 to 1646)

Sun-Jata becomes a hunter and enters the bush increasing his nyama. He mocks his weak brother by bringing him the tail of each animal he kills, that part with the greatest amount of nyama. Later, Sun-Jata’s sacrificial dog devours Dankaran Tuman’s dog, exhibiting another omen of his future success.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1647 to 1669)

Saman Berete cannot bear any more, so she demands that her son Mansa Dankaran Tuman, who has ascended to the throne, cast Sun-Jata out, along with his mother, his sister Sugulun Kulunkan, also a powerful sorceress, and his brother Manden Bukari. Sun-Jata weeps, and his mother consoles him.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1670 to 1777)

Sun-Jata now begins his exile (8) by visiting the blacksmith patriarch, Jobi, the Seer (diviner), and Tulumbèn, King of Kòlè. They both fear his nyama and turn him away and for good reason. He comes to Bukari Janè, Patriarch of the Magasubaas, who is away on the ḥajj. Sun-Jata sacrifices Bukari Janè’s unborn child releasing enormous nyama, over which he gains control, adding it to his power. He comes to the nine Queens-of-Darkness but there he meets his match, and they conjure against him.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1778 to 1909)

Meanwhile, back in the Manden, Mansa Dankaran Tuman sends his daughter as enticement together with Sun-Jata’s personal Kuyatè bard, Doka-the-Cat, to the country of Susu to enlist the help of a powerful blacksmith sorcerer Sumamuru Kantè, requesting him to help destroy Sun-Jata. Doka finds Sumamuru absent, but is told that Sumamuru performs his sorcery by playing his balaphone (balan). (9) A hawk delivers the mallets to Doka, and he summons Sumamuru by playing the balaphone. Mansa Dankaran Tuman’s plan fails when Sumamuru forces the Kuyatè bard into his own service by crippling him and shaving his head (10) He renames him Bala Fasake Kuyatè. (11) Sumamuru declares war on the Manden and subdues it, silencing all opposition, and ruling with an iron fist. Mansa Dankaran flees to a far-away land to save his life.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 1910 to2036 )

Sumamuru sends Sanginugu messengers to the nine Queens-of-Darkness with a red bull as a sacrifice to slay Sun-Jata. But Sun-Jata transforms himself into a mighty lion and slays nine water buffaloes for the nine queens. They ally with Sun-Jata and pray to the prophet Muḥammad invoking his aid. Thus Sun-Jata again gains baraqah, transforms himself into a hawk, and continues his exile into the land of the Tunkaras in Mèma

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines to2037 to 2225)

Kabala Simbon the bard reveals to Sun-Jata how to play the deadly sigi-game, because losing the game will forfeit his life. Again, nyama is at stake, but Sun-Jata wins the game and thus adds more nyama to his store.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2226 to 2404)

Sun-Jata’s brother tries to usurp his power, but his sister Sugulun Kulunkan neutralizes him with her nyama. People from the Mande come and ask Sun-Jata to return and take the throne away from Sumamuru. [Fa-Digi brags about being asked to perform on Radio Mali. He begins to address his poem to a new person named Garan.]

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2405 to 2537)

Sun-Jata offers sacrifices to his fetish to strengthen his nyama for his return to the Manden. His mother dies as an omen of his succession. The Mèma king refuses to allow this powerful sorceress to be buried in his land, but his soothsayers warn that he will suffer for his refusal, and Sugulun is buried. Sun-Jata and his sister prepare to return to the Manden.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2538 to 2667)

For fear of Sumamuru, the king of Mèma resists Sun-Jata’s departure, but to no avail, and Sasagalò, the boatman, carries the party over the river after rejecting gifts to the contrary from Sumamuru. Sun-Jata attacks Sumamuru several times, but his nyama is not strong enough to overcome the Dark Wizard.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2668 to 2745)

Sun-Jata’s sister seduces Sumamuru and learns the secret of his nyama: he has conjured powerful objects, placing them on the borders of the Manden. Sugulun Kulunkan returns to Sun-Jata and reveals the secret of Sumamuru’s hidden border fetishes.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2746 to 2827)

Meanwhile, Sumamuru has stolen Fa-Koli’s wife, angering this powerful warrior, who transfers his loyalty to Sun-Jata. Fa-Koli prepares counter sacrifices to neutralize Sumamuru’s border fetishes, leaving him open to attack.

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2828 to 2887)

Sun-Jata and Fa-Koli attack Sumamuru and defeat him, chasing him to the town of Kulu-Kòrò, where he “dries up.” A sorcerer with so much nyama cannot be killed, but he transforms himself into a sacred fetish.(12)

(Follow Fa-Digi’s lines 2888 to 3083)

At long last, Sun-Jata becomes king in the Manden. He rescues his bard Bala Faseke Kuyatè who was enslaved by Sumamuru. He makes Tura Magan Tarawere his general. The expansion of the Manden empire is begun with the conquest of the Gambia. The bard ends his epic with the line: “Let us leave the words right there.”

Boston University College of Arts & Sciences

African Studies Center, Outreach Program, Massachusetts 02215

Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali Reading Guide

Lenna Dower Milton Academy, Milton, MA

Central OregonComminityCollege, Cora Agatucci, HUM 211 Course Pack: Epic of Sundjata

Sundiata, Office of Resources for International and Area Studies, Berkeley, CA 94720-2318

The following questions are geared toward a discussion of the Epic of Son-Jara in the context of the upper-level undergraduate course Nobility and Civility: East and West (Columbia University global core).* A syllabus of the course can be found here.

Sisòkò, Fadigi (text), John William Johnson, et al (analytical study & translation), The Epic of Son-Jara: A West African Tradition. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1992. Pp. 20-101.

This story about the founder of the Empire of Mande, in West Africa (c1230-c1600s), is still widely recited today. Some elements are no doubt specific to the culture, but which features resonated most with you?

The editor and translator of the version we read (John W. Johnson) writes that Son-Jara is “ the paramount culture hero of most of the Mandekan speaking peoples. His life serves as a contemporary role model, not admired but copied, for any person who might choose to pursue an ambitious life’s course” (7). In your view, what characteristics make him an imitable model? What instead makes him exceptional/unique? What ideals and values emerge through his actions?

What characteristics stand out in comparison to other heroic figures we’ve encountered in previous readings (Gilgamesh, Rama, Arjuna, Seyavash, or even Alexander of Macedonia)? Some topics to compare could be: the hero’s value scale; family dynamics, from bonds of love or duty to divisive envy/resentment; strong driving emotions propelling action; exile; injustice; warfare; hospitality or lack thereof; a sense of destiny or fate either helping or hindering the hero; political structures and power).

One aspect that sets Son-Jara apart from other heroes is that he is unable to walk for the first nine years of his life. What does this initial disability (and the way it is overcome) add to our understanding of his trajectory? What does it serve to reveal about those around him through the manner in which they treat him and his mother? What do his initial actions after gaining his mobility reveal about him (especially uprooting and replanting the baobab tree behind his mother’s house)? In general, how does the hero overcome obstacles?

Although some of the female characters have no agency (e.g., Bukari Jane’s pregnant wife killed to offer her unborn child to a fetish to help Son-Jara), others take action at crucial moments in the story. Think about ways to compare the following female characters: 1) Du Kamisa, who transforms herself into the Buffalo-Woman of Du; 2) Sugulun, who is initially covered in “warts and pustules,” refuses the sexual advances of the Tarawere Dan Mansa Wulanba, gives birth to Son-Jara, helps her son to walk, and accompanies him in exile; 3) Son-Jara’s sister, who makes possible his ultimate triumph over his enemy; 4) the nine Queens-of-Darkness who are persuaded to help Son-Jara.

There is some erasure of boundaries between the human and animal realm: what do Du Kamisa’s transformation into a wild buffalo and Son-Jara’s transformation into a lion suggest about human emotion and action?

Why might the story of Son-Jara go back not only to the previous generation but all the way back to the creation of humankind in the “Prologue in Paradise”? What are some meaningful differences between this initial account and the Adam and Eve story in Genesis?

What function(s) might the frequent genealogies serve?

Are the violent conflicts and injustices that occur due more to: 1) the flaws in human nature; 2) tensions inherent to social, political, or family hierarchical structures; 3) personality traits of the various actors; 4) fate; 5) other?

What do you make of the following two recurring statements:

“What sitting will not solve, / Travel will resolve.” (Is it used with the same connotations/implications throughout?)

“A man of power is hard to find. / All people with their empty words, They all seek to be men of power” (167).

What are the implications about the human condition that might be gleaned from the various stages of Jon-Sara’s trajectory? Is there an underlying philosophy of life expressed in the story?

Our text is a linear translation of a four-hour performance from 1968. Which parts of the work might be rendered most effectively through verbal art?

Fun facts:

Although the plot is not the same as Disney’s The Lion King, Son-Jara is sometimes referred to as the original Lion King.

The bard mentions balaphones (pp. 193-5). Here’s an example of balaphone playing in Mali from youtube.com: Balafon in Mali from DVD

Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University)

*This two-semester course was designed through the Faculty Workshops for a Multi-Cultural Sequence in the Core Curriculum (Heyman Center for the Humanities, 2002-2009), directed by the late Wm. Theodore de Bary, at Columbia University.