Saint Lucia (West Indies)

Published: 1990

Derek Walcott

Omeros

Omeros (1990) upends the conventions of canonical Western epics by turning Caribbean fishermen into twentieth century heroes. In its titular allusion to Homer as well as in its topical and formal engagement with Joyce’s Ulysses, Virgil’s Aeneid and Dante’s Divine Comedy, the poem acknowledges its debt to earlier European epics. Yet it also condemns the societies which produced those works, as their veneration of Homeric themes of war and violence buttressed their defenses of colonialism and the slave trade.

Written in Dantean terza rima, (a meter which presents the passage of time as both repetition and relentless forward momentum) the poem is set in late-twentieth century St. Lucia sometime after independence. Its central characters are marked by their historical inheritances. Hector and Achille are fishermen, descendants of African slaves, as is Helen, the love of both of these men.

Major Plunkett, an Englishman, is a veteran of the North African Campaigns of World War II, and his wife, Maud, an Irish transplant in the Caribbean. The poet makes appearances himself, and alludes regularly to his mixed Dutch, British, and Congolese genealogy. Derek Walcott, first winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature to hail from the Caribbean, was born in 1930 in St. Lucia, the central setting for Omeros.

The poem has a wide enough berth to also include a diverse array of other characters including the blind Seven Seas (a stand-in for Homer) and Philoctete, whose unhealing wound is caused by the Middle Passage. In total, these and others Walcott includes reflect the Caribbean’s modern history as a “contact zone” or crossroads at which indigenous Carib people encountered African slaves and the European colonists who conscripted them into forced labor on sugar plantations. The themes of trauma and contact develop over 500 pages, split into seven books which are further divided into chapters. The poem travels geographically out from St. Lucia, through Europe, the Congo, and into North America. It also moves back through time into the early days of slave raids on the coast of West Africa, to the plains of the nineteenth-century American Midwest during westward expansion, and to the 1782 Battle of the Saintes between France and Great Britain that solidified British rule in the Caribbean.

Walcott’s repurposing of the epic form to produce a historical narrative of our modern era also draws from the confessional poets of the twentieth century to gesture at the ways that individual fates (the author’s as well as his characters’) are bound within historical events. Walcott writes: “Time is the metre, memory the only plot” (129), binding his own personal experiences tightly to the temporal trajectory of historical time.

In his 1961 classic The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon links the epic to colonial historiography, proclaiming that it is “the colonist [who] makes history. His life is an epic, an odyssey” (14). For Fanon, the narrative of imperialism is always written at a hyperbolic scale, relying on exaggeration, hagiography and Homeric epithets. And thus Walcott appropriates the excess of the epic form in order to equate St. Lucia with Ancient Greece, exalting the everyday man and woman to make them the heroes of our contemporary world.

In a famous passage, Walcott describes female mineworkers in St. Lucia who carry coal up a hillside in a rote circular motion of unceasing effort. He compares them to ants, suggesting that the stories of the “ants” deserve to be elevated to the importance of the characters in Homer’s two great epics—that their lives and experiences are as weighty and as deserving of literary remembrance and immortalization as the “great warriors” of Ancient Greece. The themes of love and war so famously linked to the epic genre apply necessarily, for Walcott, to these abandoned figures of history. To depict them with “epical splendor” is the use to which Walcott puts the genre, renovating its emphases on longevity and size for new purposes in our postcolonial present.

Lily Saint

Wesleyan University

Fanton, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Trans. Richard Philcox. c1961. New York: Grove Press. 2004.

Walcott, Derek. Omeros. New York: Farrar Strauss & Giroux, 1990.

Resources

Derek Walcott reads from Book 1, Chapter 1, of Omeros (A Century Of Poets Reading Their Work):

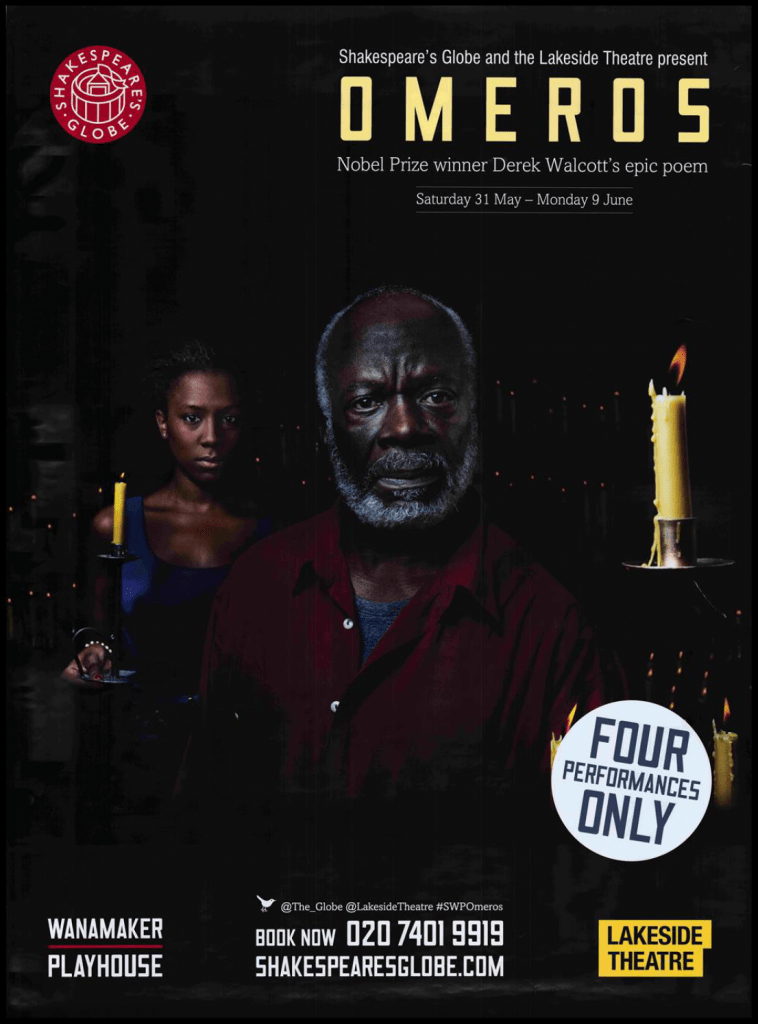

Derek Walcott’s “Omeros” returns to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

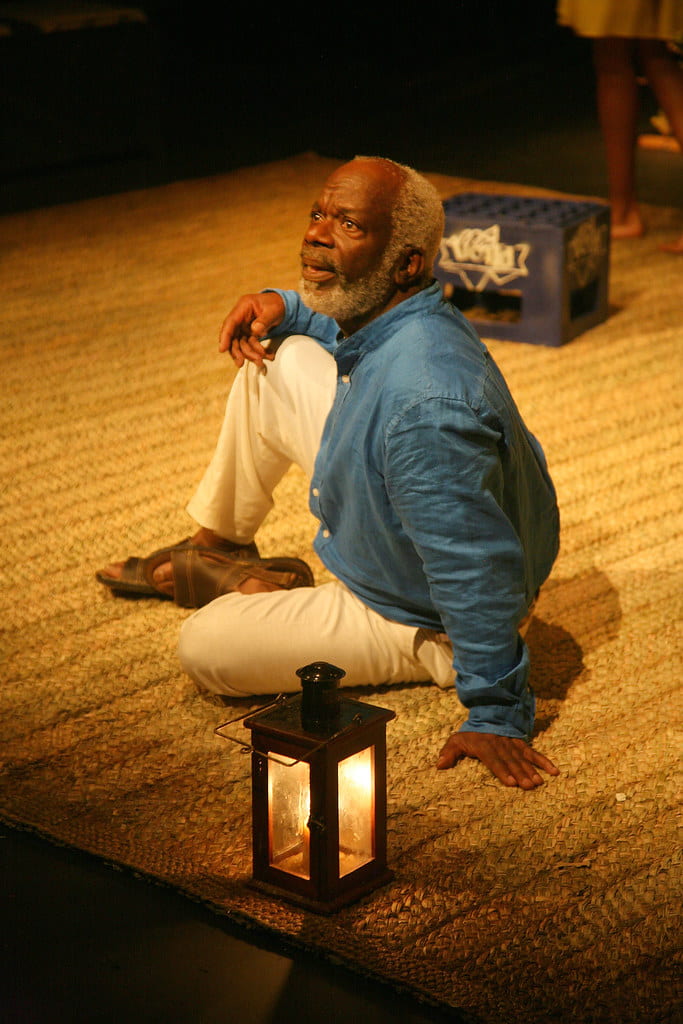

An extract from the production of Omeros, spoken by Joseph Marcell, on the occasion of National Poetry Day (2015):

Posters from the staging of Omeros by Shakespeare’s Globe and the Lakeside Theater: