Russia

The tradition originates in the 10th or 11th century; the first extant transcriptions are from the 17th century.

Anonymous,

bylinas

(traditional Russian epic songs)

Among Eastern European Slavic folk genres, the bylina–an epic song about the heroic deeds of mighty warriors (bogatyrs)–holds a special place. This term, derived from the past tense of the verb “byt’” (“to be”) means “what happened in the past.” Bylinas were performed by a singer (in medieval times, there were professional ones similar to European minstrels), often with the accompaniment of a gusli (a zither-type stringed instrument). Each bylina relates episodes from a hero’s life and exists in numerous versions. Folklore researchers have calculated that there are more than 50 plots of bylinas.

Since the 1800s when bylinas began to be printed, the genre has been the source of probably the most passionate arguments among folklore researchers, who have posited a variety of theories regarding its origin as well as the best interpretive approaches. While the “mythological” school attributed to the characters symbolic features of ancient Slavic deities connected to the natural elements, the “borrowing”/”migration” theory supporters pointed to the similarities to some storylines of European and Asian folklore, and the “historical” school explained these songs’ content as a distorted reflection of real events. Nowadays it is considered proper to see a mixture of different elements in a bylina: “fossils” of Slavic Paganism and matriarchate, fragments of past events (the Tatar-Mongol invasion, Ivan the Terrible’s reign, and Polish intervention during the Time of Troubles), traces of Eastern and Western migrating tales (including fabliaux), as well as Christian hagiography and apocrypha. The content of the bylinas, moreover, was influenced by a variety of features of Slavic folklore genres, such as magic tales, historical and wedding songs, ballads, toponymical legends, and charms.

The geographical origin of bylinas has also been debated at length. Given that several mention Kiev, the capital city of Kievan Rus, the majority of folklore researchers agree that this area was the site of the genre’s inception. Scholars also point to other medieval principalities as possible centers of creation of bylinas: those of Galicia and Volhynia, Rostov and Suzdal. Those songs would have later reached the North-East, North-West, and the North. The majority of those songs were recorded in the 19th century in the North; fewer were recorded in Siberia, by the Volga and the Don Rivers, and other areas. The performer of a bylina, called a “skazitel” (derived from the word “to tell”), was usually of a middle class origin, often a craftsman. Sometimes a skillful teller was invited to join a team of fishermen or lumberjacks, and received an equal or larger share from the seasonal common earnings. The best performers, among whom were sometimes a few generations of singers from the same family, remembered thousands of bylinas lines.

The epic songs of the so-called “Kievan” series are believed to have historical figures as prototypes of the main characters. For example, stories mentioning Prince Vladimir, called the Red Sun, possibly refer to the famous ruler Vladimir Svyatoslavovich. Bylinas describe his court with its feasts as the place where the best warriors gathered, similarly to King Arthur’s Camelot. Another series of songs called “Novgorod’s” tell about the rich city of Novgorod the Great in the North-West. This group does not include the themes of protecting the country and of heroic battles typical of the “Kievan” series, but rather contains stories about a rich merchant and talented gusli-player (Sadko) and a mighty troublemaker (Vasily Buslaev).

The schools of folklore researchers have also interpreted the main characters of bylinas in different ways. For example, the “mythological” school has divided them into the “older” and the “younger.” The former would represent the earliest “layer” of the content connected to Eastern Slavic deities while the latter would reflect the Kievan period or even later when the Principality of Moscow became the new country’s unifying center following the Tatar-Mongol invasion. Some scholars have based their analysis of the bylina on the chronology related to the invasion: prior to the establishment of the Tatar-Mongol yoke, during the occupation, and after it (up to the 15th century). In this respect, “Novgorodian” bylinas are considered a separate group because that area was not seized, and the locally developed plots would thus reflect the inner conflicts of that prosperous medieval city-republic (12th – 15th centuries).

Probably the most popular bylina character is the knight Ilya Muromets, who was the son of a peasant. According to the hagiography of the Orthodox Church, this warrior became a monk in his advanced years, which is probably why these songs emphasize Ilya’s piety. On the other hand, the folklore image of the knight is often mixed with the figures of both Elijah the Prophet and the highest Slavic deity, Perun, showing features of religious syncretism. The stories about Ilya’s adventures usually tell how he protects the country and easily defeats a huge invading army thanks to his physical strength, confidence, wisdom, and patriotism. Dobrynya Nikitich is the second most popular hero of the bylinas. His prototype was possibly Prince Vladimir’s uncle, Dobrynya. Perhaps this is why Dobrynya is described as a well-mannered, educated man often sent by the Prince on some quest, one of which was freeing Vladimir’s niece from a dragon. Another popular warrior is Alyosha Popovich. He is brave, smart, and handsome even though he is not very strong in comparison with other knights, and in some stories he plays an unattractive role as a seducer.

A noteworthy feature of some bylinas is the presence of mighty female warriors called polenitsas, such as the intelligent and courageous sisters Vasilisa Mikulishna and Nastasiya Mikulishna. A polenitsa often marries the knight who manages to defeat her. Historians have seen the roots of these plots in the interaction of the Slavs with the Sarmatians, whose culture had vestiges of matriarchy, or in some neighboring Turkic ethnic groups, whose epics contain stories about female warriors.

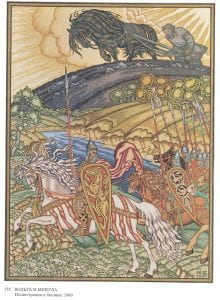

While Ilya, Dobrynya, and Alyosha, as well as the polenitsas, are referred to as the “younger” knights, the bylinas about mighty giants like Svyatogor are studied outside of the “Kievan” and “Novgorodian” series because of their connection to the pre-Christian cult of Mother Earth. Svyatogor is so strong that he boasted that he could flip over the sky and the ground. The symbolic link of this chthonic deity-like giant to the Kievan warriors is his meeting with Ilya, to whom the dying Svyatogor transferred a part of his power. There is an even stronger giant, however, among the “older” characters: the plowman Mikula Selyaninovich, father of the two above-mentioned polenitsas, who is able to lift a bag with an “all-Earth weight.” This mighty peasant is connected to both the pagan cult of Mother Earth and St. Nicholas. Some researchers consider the bylinas about a mysterious Vol’ga to be a part of this series. This Prince-wizard was born from a snake and a princess, and his distinctive features are his superior physical strength, his ability to shape-shift, and his comprehension of the animals’ language.

The content of bylinas–including their main characters’ exciting adventures, heroic deeds in protecting the country from invaders, dangerous quests, encounters with magic creatures, and love stories–have been an inspiration for numerous artists like V. Vasnetsov, M. Vrubel, I. Repin, and N. Roerich, who created their paintings in a variety of styles from Art Nouveau and Symbolism to Realism. The same reasons attracted such prominent 19th-century composers as A. Borodin, M. Mussorgsky, and N. Rimsky-Korsakov to these epic songs. In the 20th and 21st centuries, bylinas’ stories have been often featured in film and cartoon scripts. These traditional epic songs are still a rich source of inspiration for other forms of national art.

Yelena P. Francis

Columbia College (MO)

Resources

Bylina in English translation:

Bailey, James, and Tatyana Ivanova, translators and editors. An Anthology of Russian Folk Epics. Routledge, 1998.

Wratislaw, A. H., editor and translator. Sixty Folk-Tales from Exclusively Slavonic Sources. 1890. Library of Alexandria, 2009.

The above bibliography was supplied by Yelena P. Francis, Columbia College (MO).

The illustrations for bylinas:

- Viktor Vasnetsov. Knight at the Crossroad (from the bylina about Iliya Muromets

- Viktor Vasnetsov. Warrior Knights.

- Viktor Vasnetsov. Knightly Galloping.

- Viktor Vasnetsov. Dobrynya Nikitich is Fighting the Dragon.

- Ivan Bilibin. Dobrynya Nikitich is Saving Zabava Putyatichna.

- Ivan Bilibin. Alyosha Popovich.

- Ivan Bilibin. Iliya Muromets and Svyatogor.

- Ivan Bilibin. Iliya Muromets and Nightingale the Brigand.

- Ivan Bilibin. Volga and Mikula (1902)

- Ivan Bilibin. Volga and Mikula (1903)

- Ivan Bilibin. Volga and Mikula (1904)

- Ivan Bilibin. Volga and Mikula (1913)

- Ivan Bilibin. Volga and Mikula (1940)

- Nicholas Roerich. Iliya Muromets.

- Nicholas Roerich. Mikula Selyaninovich.

- Nicholas Roerich. Victory (Gorynych the Serpent)

- Nicholas Roerich. Svyatogor.

- Mikhail Vrubel. Bogatyr.

- Mikhail Vrubel. Princess Volkhova. (from the bylina “Sadko”)

- Mikhail Vrubel. The Sea King and Princess Volkhova. (from the bylina “Sadko”)

- Mikhail Nesterov. Iliya Muromets.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. The Feast of Warriors at Prince Vladimir’s court.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. Blind Guslyar singing a bylina.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. Alyosha Popovich.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. Mikula Selyaninovich.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. Vol’ga Vseslavievich.

- Andrei Ryabushkin. Svyatogor.

- Iliya Repin. “Sadko in the Underwater Kingdom”

- Viktor Vasnetsov. Guslyary.

- Orthodox Church icon “Iliya Muromets”

- Saint Elias (Ilya) Muromets of the Kiev Near Caves.

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Sadko and Sea Tsar”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Alyosha Popovich and Lovely Maiden”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Vasily Buslaev”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Birth of the Danube”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Svyatogor’s Gift”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Iliya Muromets Releazes the Prisoners”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Nastasiya Mikulishna”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Sadko”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Dobrynya’s Battle with a Dragon”

- Konstantin Vasiliev. “Vol’ga and Mikula”

- Folk print. Rovinskii, D. A. “Alyosha Popovich, a mighty warrior.”

The above images were selected by Yelena P. Francis, Columbia College (MO).

Bylinas in Music.

- Rimsky-Korsakov. Opera “Sadko”. Bolshoi Theater. 1980

- Rimsky-Korsakov. “Sadko” Symphony picture.

- Borodin. Symphony # 2 “Bogatyrskaya”.

- Mussorgsky. “Pictures at an Exhibition”. (# 10) “Great Gate of Kiev”.

- Gliere. Symphony # 3. Op. 42. “Iliya Muromets”. WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln

- Gliere. Symphony # 3. Op. 42. “Iliya Muromets”. The Orchestra Now (TŌN)

- Balakirev. “Bylina”.

- Kalinnikov. Overture “Bylina”.

- Grechaninov. Opera “Dobrynya Nikitich”: Part 1, Part 2.

- Feoktistov. Opera “Iliya Muromets” (fragments)

Films:

- “Sadko” by A. Ptushko (1952), with English subtitles.

- “Iliya Muromeths” by A. Ptushko (1959). In Russian.

- “Vasily Buslaev” by G. Vasiliev. 1982. In Russian.

Performance of Bylinas

- Bylina “Iliya Muromets and the Nightingale Brigand” performance accompanied with gusli (Russian medieval psaltyri).

- Egor Strelnokov. “Iliya Muromets and Evil Spirits”

- Irina Pyzhyanova. Bylina “Iliya Muromets”

- Dmitry Paramonov. “Iliya Muromets on Sokol Boat”.

The above selection of performances was compiled by Yelena P. Francis, Columbia College (MO).

- Statue of Iliya Muromets. By V. Klukov and V. Talkov. Murom City. Russia. 1999.

- Statue of Iliya Muromets. Kiev’s park “Muromets”. Ukraine. 2018.

- Monument to Iliya Muromets as a saint. By K. Zinich. Vladivostok. Russia. 2012.

The above list of monuments was compiled by Yelena P. Francis, Columbia College (MO).