England

12th century CE

Bevis of Hampton

(Boeve de Haumtone)

Bevis of Hampton may be little known today but for centuries he enjoyed immense popularity throughout Europe. Having made his first appearance in an Anglo-Norman (i.e., written in England, but in French) chanson de geste in the late twelfth century, the hero was still popular in Russian nineteenth-century chapbooks, his adventures performed by storytellers and puppeteers in Italy in the twentieth century.

The twelfth-century Anglo-Norman chanson de geste known as Boeve de Haumtone is the work of an anonymous author – or maybe of two authors separated by a couple of decades, in an early example of a later author capitalizing on the success of a story by providing it with a sequel. Circumstantial evidence suggests that at least one of the authors, if not both, could have been close to the family of the d’Aubigny earls of Arundel. What is certain is that in composing the text the author(s) drew on the rich storehouse of both chanson de geste and the more recent genre of romance. It is to this ingenious deployment and transformation of a number of standard literary motifs, many with a lengthy folkloric history, that the story owes its long-lived appeal.

Here is a brief plot outline of the story in this earliest form, in which the hero’s name appears as Boeve. When his wicked mother arranges to have her ageing husband, Earl of Hampton (in English texts increasingly often referred to as Southampton), killed by her lover Doun, the emperor of Germany, the boy hero is sold into slavery and ends up at the court of King Hermin in Egypt. (In the second part of the narrative, Egypt inexplicably becomes Armenia; this is not the only inconsistency between the two parts.) Hermin’s daughter Josiane eventually falls in love with him. It is from her that he receives the horse Arundel, a faithful companion for many years. After Boeve’s successful campaign against a hostile foreign king, Brademond, Josiane declares her love. Boeve does not reciprocate until assured that she will convert to Christianity, which she readily promises. Soon afterwards the hero is falsely accused of having slept with her. Too fond of the young man to order his execution, Hermin sends him to Brademond, now Hermin’s vassal, with a letter ordering that the bearer be imprisoned for life; accordingly, as soon as he arrives Boeve is thrown into a deep dungeon. Meanwhile Josiane endures a forced marriage to Yvori, king of Monbrant. She uses a magic girdle to preserve her virginity for seven years, which is how long it takes Beuve to manage to escape from captivity. Once he is free, Boeve comes to Yvori’s castle disguised as a pilgrim, rescues Josiane and Arundel, and flees with them to the forest. There he kills two lions and subdues the giant Escopart, whom Yvori has sent to retrieve his wife. Escopart becomes Boeve’s page and the fugitives eventually reach Cologne, where the bishop, Boeve’s uncle, baptizes both Josiane and Escopart.

Boeve returns to England to reclaim his heritage but is recalled to Cologne by bad news: Josiane was forced into marriage with Earl Miles, whom she strangled on the wedding night; she is now condemned to burning at the stake. Boeve and Escopart arrive in time to save her, then travel together to England, where Boeve finally wrests his earldom from his stepfather. Doun is killed, Boeve’s mother kills herself, and Boeve and Josiane are married. (This, in all likelihood, is where the original version of the story ended.)

Boeve, now earl of Hampton, is warmly received by King Edgar, who showers him with honours. Their relationship soon sours, though. Boeve wins a horse race organized by the king, then uses the prize money to build a splendid castle, named Arundel in honour of his horse. But the horse is coveted by the king’s son, who tries to steal it and is kicked to death by the faithful animal. Leaving his earldom to his tutor and protector Sabaoth, Boeve goes into exile again, accompanied by a heavily pregnant Josiane. In a forest, Josian gives birth to twin boys, whom Boeve does not get to see because Josiane and the babies are immediately carried off by Escopart, who has transferred his loyalty back to Yvori. Sabaoth learns of the kidnapping in a dream and hurries to rescue Josiane, killing Escopart. For seven years, Sabaoth and Josiane seek the hero, not knowing that he has married the duchess of Civile. (The marriage remains unconsummated.) In the end the family is reunited, one of Boeve’s sons succeeds Hermin as king of Egypt, while Boeve himself wins the throne of Monbrant by killing Yvori in single combat.

Meanwhile Sabaoth’s son Robant, in charge of the earldom of Hampton, is harassed by King Edgar. When Boeve returns to England to help him, the terrified king sues for peace, offering his daughter’s hand in marriage to Boeve’s other son. (In a famous episode found only in the Middle English versions of the story, the king’s steward stirs up the citizens of London against the hero, giving rise to a street battle in which thousands are killed.) With both sons provided with realms, Boeve and Josiane return to Monbrant, where they and Arundel all die on the same day.

The fast-paced Anglo-Norman narrative packs a multitude of incidents and characters into its scant 4000 lines: the above plot summary omits all but the most essential. As noted earlier, it is also very rich in popular themes and motifs, a number of them resonating with the original poem’s socio-political context. Thus the age-old pattern of a dispossessed prince’s exile and triumphant return often acquires political overtones in twelfth-century England, reflecting tensions between king and magnates. Josiane is an enterprising wooing woman, a character type derived from chansons de geste, but she is also contrasted with Boeve’s mother, a young woman murderously embittered by her marriage to a much older man. Echoes of contemporary debates about the importance of consent in marriage are obvious. The mother’s Scottish origins may reflect contemporary tensions between England and Scotland, just as the identity of her lover may draw on Insular ambivalence regarding several twelfth-century German emperors. The Middle Eastern setting of large parts of the plot satisfies the perennial taste for exoticism while also capitalizing on the growing interest in the area at the time of the First Crusade. The prominence of the East in the story introduces interesting tensions in the portrayal of the protagonist. He strongly identifies with the West and insists on his place in the top echelons of the English aristocracy. Christianity looms large in his sense of who he is. Yet he grew up in the East, where his identity as a Christian Westerner was no major obstacle to social advancement. As an adult he also spends much of his time in the East; he gives up his earldom in England to rule an Eastern kingdom, and that is where he and his wife, a converted Eastern princess, end their lives. In fact, Boeve’s trajectory is not unlike that of some early Crusaders, who settled in Outremer while maintaining ties with their ancestral lands. Accordingly, the Anglo-Norman hero’s attitude to the Muslim Other is more pragmatically balanced than that of his Middle English avatar, Bevis, whose zeal in killing “Saracens” is paralleled only by his intense and ostentatious Englishness. Boeve converts pagans more often than he kills them, and he offers no parallel for Bevis’s intense and vocal identification with England.

Boeve, in fact, did not acquire the status of national hero until he was translated into English. The Anglo-Norman narrative travelled light, and that is probably why it travelled so far: freedom from nationalist baggage greatly facilitated its protean transformations in Europe. Only the Irish version, produced in the fifteenth century, was translated from a Middle English redaction; it may have been produced for a family with strong ties to England. All the other European versions go back to the Anglo-Norman text and its descendants, in a tradition that places little emphasis on the hero’s national origins. The alacrity with which Boeve was translated and otherwise appropriated in the century after its composition is an excellent indicator of the story’s attractiveness and popularity. It was the source of the Middle Welsh Ystorya Bown o Hamtwn (mid-thirteenth century) and the Icelandic Bevers saga (possibly thirteenth-century). Two Faroese ballads, Bevusar tættir and Bevusar ríma, are based on material from the first few chapters of Bevers saga. Three Continental French verse redactions, all from the thirteenth century, expanded the briskly compact Anglo-Norman narrative to between ten and twenty thousand lines. The story was then recast in French prose in the early fifteenth century, in a redaction which subsequently went through several printings. From north-eastern France, the material eventually made its way to the Netherlands, where a verse redaction, of which little remains, preceded a better-documented prose adaptation, printed texts of which begin to appear in the first decade of the sixteenth century.

It was, however, thanks to its southward move to Italy that the story eventually spread as far as Russia. The various stages in this journey were marked by narrative transformations, sometimes of a very radical nature. In Italy we encounter a multiplicity of versions composed in different dialects, shaped into different prosodic forms, and performing different functions in the broader context of the Italian narrative tradition. Franco-Venetian cantari of the fourteenth century were followed by several Tuscan versions in ottava rima, as well as versions in prose. A 1497 printing of a verse tale of Buovo (or Bovo) d’Antona, as the hero is usually called in Italian, was the source of Elia Levita Bachur’s translation into Yiddish, Bovo-Buch, composed in 1507 and first published in Venice in 1541. One of the most popular narratives in Yiddish secular literature for five hundred years, Bovo-Buch was translated into Romanian as late as 1881. In Italy itself, an important fourteenth-century Franco-Italian redaction, part of a compilation attempting to merge different stories from the Carolingian cycle into a unified whole, served as the basis of Andrea da Barberino’s lengthy prose romance I reali di Francia, first printed in 1491 and endlessly reprinted throughout the sixteenth century. Readers familiar with the Anglo-Norman and Middle English versions might not immediately recognize the much-amplified story or some of the characters, changed in ways that go beyond the simple substitution of one name for another: Escopart, for example, becomes Pulicane, half-man, half-mastiff. But, despite numerous substantial changes, the principal episodes of the original narrative remain in place until the latter part of the text, when Buovo engages in military campaigns in Central and South-Eastern Europe (rather than in the Middle East), before dying at the hands of his half-brother Gailone.

It is in this form that the story attained its greatest popularity and, from the sixteenth century, spread eastwards by way of Venice. In 1549, twenty copies of the Italian Buovo d’Antona were shipped from Venice to Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, Croatia). With its population of educated Slavs fluent in Italian, this city-state on the Adriatic coast was an ideal conduit for Western cultural goods; thus, when the story surfaced in a Byelorussian manuscript (now in Poznań, Poland) some decades later, it was in a form that showed both its derivation from an Italian version current in Venice and traces of its passage through Balkan lands. The quickly multiplying Russian versions are all traceable to this Byelorussian text. In Russia, Bevis, now called Bova, reached the apex of his social ascent. Whereas in the West the story was almost certainly never read at royal courts, in 1693 an illustrated copy of a Russian redaction was among the books enjoyed by Peter the Great’s young son Alexis. The story appealed to all social strata and was transmitted orally, in manuscript form, in chapbooks and in broadsheets, throughout the nineteenth century and, in the form of oral folk narratives, into the twentieth.

In Italy too, we find continuing interest in the story. In 1758, composer Tommaso Traetta teamed up with the librettist Carlo Goldoni to turn a romantic episode from the story into a comic opera in three acts, first performed in Venice. The comedy must have derived part of its appeal from a radical reversal of the audience’s expectations. To the extent that they were familiar with Buovo’s life and adventures, listeners would have expected his courtship of Drusiana (Josiane’s name in the Italian tradition) to result in their marriage, as in the narrative tradition. Instead, Drusiana is tricked into marrying Buovo’s rival, while the hero eventually finds happiness with a miller’s daughter. In some parts of Italy, just as in Russia, Buovo’s exploits attracted and entertained popular audiences as late as the twentieth century, especially in Sicily, where they became part of the repertoire of storytellers (cuntastorie) and puppeteers (pupari).

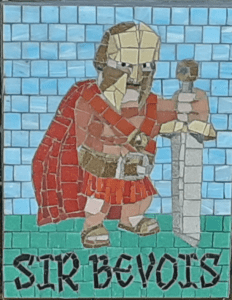

The days of Bevis’s Europe-wide fame are over, but he remains a living presence as a local folk hero in parts of Hampshire and Sussex. Street and place names in and around Southampton preserve the memory of the protagonist and other characters: wooden panels depicting Bevis and Escopart were once displayed on the outside of the city’s Bargate and are now inside the Bargate Museum; characters from the romance are represented by gargoyles on the tower at St Peter’s church, Curdridge (built in 1878); while a small mosaic portraying SIR BEVOIS appeared overnight on a Southampton street in 2020 (see featured image on this page). In Sussex, a tournament sword in the armoury of Arundel Castle (which, according to the Middle English romance, was built by Bevis and named in honour of his horse) bears the name Mongley.

Ivana Djordjević (Concordia University) and Jennifer Fellows (independent scholar)

Resources

EDITIONS & TRANSLATIONS

Considering the richness of the tradition, this list had to be highly selective.

Anglo-Norman

Jean-Pierre Martin, ed. and transl. Beuve de Hamptone: chanson de geste anglo-normande de la fin du XIIe siècle. Champion Classiques. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2014. [With parallel translation into modern French.]

Judith Weiss, transl. “Boeve de Haumtone” and “Gui de Warewic”: Two Anglo-Norman Romances. French of England Translation Series. Tempe, AZ: Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 2008.

Middle English

David Burnley and Alison Wiggins, eds. The Auchinleck Manuscript. Edinburgh: National Library of Scotland, 5 July 2003, version 1.1. [A transcription of the text in National Library of Scotland Advocates’ MS 19.2.1, with links to manuscript images.]

Jennifer Loney Fellows. “Sir Beves of Hampton: Study and Edition,” 5 vols. (unpub. Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Cambridge, 1980). A parallel-text edition of MSS A, S (with variants from N), E, and C, together with separate transcriptions of MSS M and T, and the text of the printed Bevis, as represented by William Copland’s second printing, with variants from other early prints.

Jennifer Fellows, ed. “Sir Bevis of Hampton,” edited from Naples, Biblioteca nazionale, MS XIII.B.29 and Cambridge, University Library, MS Ff.2.38, 2 vols. EETS OS 349–350. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society, 2017. A manuscript containing what is probably an excerpt from Bevis rather than a fragment of a longer text was discovered by Ralph Hanna in the 1990s and described by him in “Unnoticed Middle English romance fragments in the Bodleian Library: MS Eng. poet. d.208”, Library, 21:4 (1999), 305–20. The text is transcribed as Appendix 12 in this edition.

Ronald B. Herzman, Graham Drake, and Eve Salisbury, eds. Four Romances of England: “King Horn,” “Havelok the Dane,” “Bevis of Hampton,” “Athelston.” Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Insttitute Publications, 1997. [Also available online: https://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams/publication/salisbury-four-romances-of-england]

Icelandic (‘Parallel-text edition’)

Christopher Sanders, ed. Bevers saga. Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi 51. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi, 2001. A parallel-text edition, allowing comparison with the Anglo-Norman Boeve.

Irish

F. N. Robinson, ed. and transl. “The Irish lives of Guy of Warwick and Bevis of Hampton,” Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie, 6 (1908), 9-180, 273-338.

Welsh

Erich Poppe and Regine Reck, eds. Selections from “Ystoria Bown o Hamtwn.” The Library of Medieval Welsh Literature. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2009.

Continental French and Franco-Italian

“Beuve de Hantone.” Archives de littérature du Moyen Age. The ARLIMA site is not fully updated, but is still an excellent starting point for research on the French and Franco-Italian versions of the story. The most important editions are listed there.

Italian cantari

Daniela Delcorno Branca, ed. Buovo d’Antona: Cantari in ottava rima (1480). Biblioteca medievale 118. Rome: Carocci, 2008.

Yiddish

Jerry C. Smith, transl. Elia Levita Bachur’s “Bovo-Buch”: A Translation of the Old Yiddish Edition of 1541 with Introduction and Notes. Tucson: Fenestra, 2003.

SCHOLARSHIP

The body of scholarship on the many versions of the story keeps growing.

The ARLIMA site above is a good starting point for research into the French versions, complemented by the bibliography in Jean-Pierre Martin’s edition.

For the English texts, an indispensable collection of essays, with an extensive bibliography of foundational scholarship, is Jennifer Fellows and Ivana Djordjević, eds. Sir Bevis of Hampton in Literary Tradition. Studies in Medieval Romance. Cambridge: Brewer, 2008. To this should be added the bibliography in Jennifer Fellows’s more recent edition for the EETS (see above).

The above bibliography was supplied by Ivana Djordjević (Concordia University) and Jennifer Fellows (independent scholar).

Illuminated page from the Taymouth Hours (London, British Library, MS Yates Thompson 13); Bevis of Hampton spearing a lion, while another lies at his feet impaled on a sword. Several images in this sumptuous manuscript illustrate episodes from the story of Bevis.

Early printed editions of Bevis of Hampton were typically illustrated with woodcuts. In this illustration from a 1630 edition, the boy Bevis tends to his tutor’s sheep early on in the narrative. One of the most popular woodcut representations is of Escopart carrying Bevis, Josiane, and Arundel on board of a ship.

Tokens stamped with Bevis’s profile, coined in England (mostly in Southampton) in the late 18th century. (Click on “related objects” to see the images.)

In the 19th century Bevis was still a popular hero in children’s books. This illustration comes from one of them.

Sicilian puppet theatre posters for performances of the story as transmitted in the Italian tradition.

The above information was supplied by Ivana Djordjević (Concordia University) and Jennifer Fellows (independent scholar).

“Bevis of Hampton.” Database of Middle English Romance, the University of York. Useful for the study of English versions.

Bevis in London. Bevis’s adventures in London, exclusive to the English versions, can be traced on this map.

“Sir Bevis of Hampton.” Historic Southhampton. This site, which contains a very detailed plot summary of the Middle English text, is focused on Bevis’s links with the city of Southampton. It can be read in conjunction with Lynn Forest-Hill’s blog, “Sir Bevis of Hampton – Local Hero,” dedicated to Bevis as a local Southampton hero.

The story now exists as a comic, Blood and Valour: Legends of the Knight Sir Bevis.

Carlo Goldoni’s libretto for Tommaso Traetta’s opera Buovo d’Antona.

IMDB entry for To Unwill a Heart, a short film based on the Bevis story.

The above information was supplied by Ivana Djordjević (Concordia University) and Jennifer Fellows (independent scholar).