Iran

12th century CE

Farid ud din Attar

Manṭiq Al-Ṭayr

(The Conference of the Birds)

This book is an ornament for the ages.

It offers something for both the high and low.

If you came sad and frozen to this book,

its hidden fire will blaze and melt your ice.

Yes, these verses are magic:

they grow more potent with each reading.

They are life beauty under a veil

that reveals its loveliness slowly. (Attar of Nishapur)

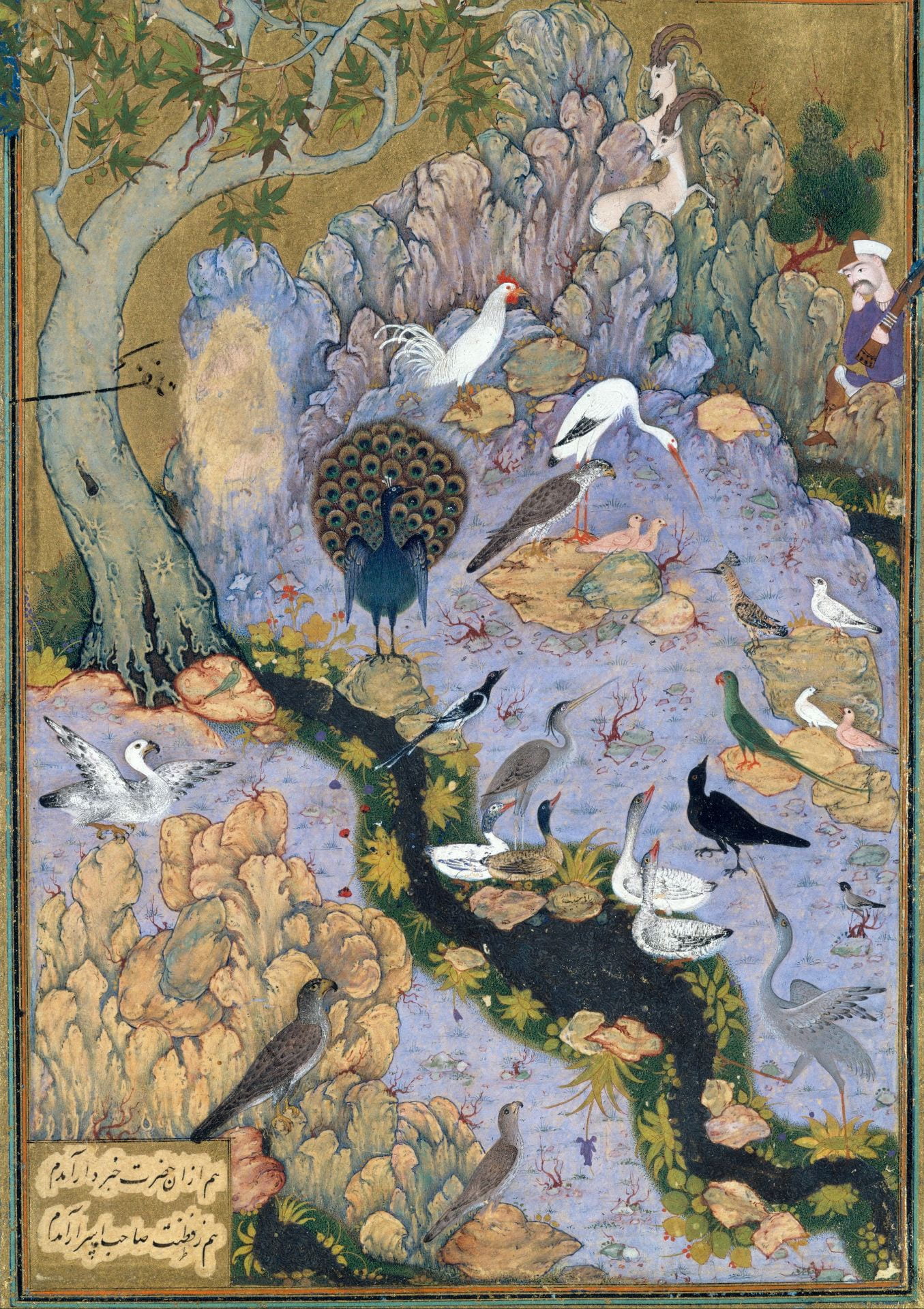

The Concourse of the Birds, Folio 11r from a Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), painting by Habiballah of Sava, detail: center right, birds. MET DT227734

The Conference of the Birds, written by the Persian poet Farid ud Din Attar, is a timeless allegorical masterpiece of Sufi literature. The original Persian title of the book is Manṭiq Al-Ṭayr (منطق الطیر). This title is directly derived from the Quran, 27:16. In this verse, Prophet Solomon, who succeeded Prophet David, informs the people that both of them had been granted the ability to understand the language of the birds (Manṭiq Al-Ṭayr). In this mystical epic, a flock of birds directed by a Hoopoe bird travels to find Simorgh, the lord of the birds symbolizing the Divine. In Persian and Sufi literature, Simorgh generally embodies ultimate truth; here it serves as a mystical destination as well. The birds of the world have to cross seven valleys, each full of treacherous challenges to reach Simorgh, who lives on the mountain Qaf, a mythological mountain range in Persian literature. In this assembly of birds, each bird represents a human flaw and attempts to make excuses to resist this call, yet the Hoopoe admonishes them against missing the chance for glory. He urges them to discard feeble characteristics and embrace the challenges of the seven valleys to attain eternal delight.

Attar’s epic narrative emphasizes Sufi teachings, and consists of 4,724 rhyming couplets in the form of Persian poetry called Masnavi. In the first part of the poem, “The Birds of the World Gather,” the Hoopoe bird, who is also said to symbolize Attar himself, acts as a messenger, summoning the birds of the world (mystics) to undertake a perilous journey to the kingdom of the venerable Simorgh. In this pilgrimage, every valley transforms the birds in myriad ways. While nearly all of them demand that the travelers forsake their weaknesses, a few also reserve epiphanies and divine realizations for them. The following brief passages describing each valley’s essence may help us to understand how they influence voyagers taking this pivotal journey.

1. “Valley of the Quest”: Here voyagers must abandon their prior convictions and beliefs. Purity of heart is a prerequisite for initiating the journey.

“There is no room here for pride, / or self-importance /or things you value and hoard.”

2. “Valley of Love”: Love conquers all, and here reason is vanquished by it.

“In this valley, love is fire, mind is smoke / When love arrives, reason flees.”

3. “Valley of Knowledge”: Here all understanding of the world becomes superfluous; the wisdom of the world takes its leave.

“Here, no path resembles the next. / Here, the traveler of the body is different / from the traveler of the soul.”

4. “Valley of Detachment”: Here the illusion of reality disappears; the desire for mundane things leaves the heart.

“Here, neither new nor ancient has any value / Here it’s all the same if you act or if you’re idle / If you have suffered a world of hardship, / Here, it’s all a dream. / If a thousand lives perish in the sea, / here, a mere dewdrop has slipped into the vastness.”

5. “Valley of Unity”: Here an epiphany reveals to the traveler that everything in the world weaves a veneer and that the Beloved lives behind that veneer.

“Arrive in the Valley of Unity / And give up everything except the absolute.”

6. “Valley of Wonderment”: Here a mere glimpse of the Beloved enchants the observer and just awe remains. Now, the traveler is devoid of reason, devoid of understanding.

“If they ask you: Are you drunk or no? / Do you exist or no? / Are you within or without? / Are you hidden or manifest?”

7. “Valley of Poverty and Annihilation”: Here the boundaries of time and space vanish because the traveler is annihilated and becomes the Beloved (fana).

“How can that be? / It’s beyond mind’s comprehension?”

Only thirty birds survive the trials of such an odyssey and reach the realm of Simorgh. The others succumb to the harshness of the journey. Those who make it into the kingdom of their Beloved realize that they themselves are the Beloved. Simorgh was naught but their own reflection. Si means thirty in Persian and morgh means birds. Here Fana (the annihilation into the Beloved) occurs.[1]

Through this allegorical journey, Manṭiq Al-Ṭayr rummages through the self, compels us to look behind the veneer of consciousness, and confronts the invisible. This epic guides its readers on a trajectory from the mundane to the eternal. This is a voyage to Simorgh’s realm that threads through daunting passages that splinter the spirit, leaving it adrift in desolation. Nevertheless, when the beloved’s glance falls upon the weary travelers, an enlightenment occurs. This enlightenment, or the recognition of one’s self, is the essence of The Conference of the Birds.

The author of this epic, Farid ud din Attar, commonly known as “Attar of Nishapur” in English, was also influenced by great Sufi poets, such as Bayazid Bastami and Mansur al-Hallaj, and that influence permeates his couplets. Both earlier poets were purported to have passed through the limitations of self and discovered the eternal one.[2] While Bastami carried God inside his cloak (Shafak 104) and introduced the concept of the “unity of existence,” Hallaj called himself absolute truth (God) (Wolpé 15). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, within the epic the Hoopoe bird symbolizes Attar. His actions liken him to a Sheikh, a figure in the Sufi tradition who leads people in the direction of greater truth and the Beloved. Yet Attar has proven to be a guide for mystics in actuality as well. Through this work, he influenced many Sufi poets of the subsequent centuries, including Jalal ud din Rumi and Hafez Sherazi. Rumi paid tribute to Attar in the following verses: “Attar traveled through all the seven cities of love / While I am only at the bend of the first alley.”

Sholeh Wolpé’s translation can be a valuable resource to read this phenomenal epic in English. Wolpe won the PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant for keeping the essence of this otherworldly book intact.[3] As Wolpé states in the introduction to her translation, her adherence to the Persian convention of gender neutrality highlights the core belief that “the human soul is without gender” (Wolpé 23). She explains, moreover, that one’s connection with the divine does not have to be confined to a religious God, but extends to the Beloved who is beyond such superficial restraints. This reflects the Sufi emphasis on the unity of human souls rather than their differences.

In sum, The Conference of the Birds creates a microcosm of the spiritual heritage that Attar leaves behind him as a cosmos to meditate upon. Even in the contemporary world, this legacy continues to emit beams of compassion and love. Attar’s statement that “these lofty words are an antidote for anyone sickened by extremism’s poison” holds considerable relevance today. The religious and political turmoil we are witnessing nowadays could be eliminated by understanding his message because Sufism represents a leaning toward mysticism without rigid adherence to traditional religious beliefs. The grandeur of Attar’s vision lies not in conformity but in the celebration of divergence. In essence, Attar’s work serves as a guiding light for us to unite in our diversity and forge a tapestry where every thread contributes to the mosaic of existence.

[1] Fana is the term used in Urdu and Persian to describe the phase in which a person loses their life in love (usually an inner death) and merges with the beloved, in Sufism, God.

[2] “The Saint Is a Mirror,” Mathnawi IV: 2102-2153 (https://www.dar-al-masnavi.org/n-IV-2102.html).

[3] https://pen.org/the-conference-of-the-birds/

Daman Khalid

Washington State University

Works Cited

Attar, Farid ud Din. The Conference of the Birds. Translation from Persian by Sholeh Wolpe. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Shafak, Elif. The Forty Rules of Love. Penguin Classics, 2015.

Wolpé, Sholeh. Introduction. The Conference of the Birds, by Attar, Farid ud Din. Translation from Persian by Sholeh Wolpé. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017. Pp. 11-24.

Resources

English Translations

Attar, Farid ud Din. The Conference of the Birds. Translation from Persian by Sholeh Wolpe. W. W. Norton & Company, 2017.

Attar, Farid ud Din. The Conference of the Birds. Translation from Persian by Sís Peter. Penguin Books, 2013.

Attar, Farid ud Din. The Conference of the Birds. Translation from Persian by Alexis York Lumbard, et al. Wisdom Tales, 2012.

Critical Essays :

Douglas, Claire. “Marie-Louise von Franz and the Conference of the Birds.” Jung Journal 3.4 (2009): 19-27.

Ekhtiar, Maryam, and Leili Anvar. Seeking Unity with the Divine.

Golab, Golshan, et al. “A Comparative Study of Love in Emerson’s Essays and Attar’s The Conference of the Birds.” International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation 3.7 (2020): 154-162.

Golbabaei, et al. “The Effect of Mythological Allusion on the Expression of Mystical Experiences (Based on the Conference of the Birds of Attar).” Journal of Linguistic and Rhetorical Studies 22 (2020): 345-368.

Khairy Abd Elnabi, Shereen. “Indicative Repetition and Its Influence on Textual Cohesion in ‘the Conference of the Birds’ by Farid Al-Din Al-Attar.” Annals of the Faculty of Arts, Ain Shams University 43 (2015): 355–400.

Kościelniak, Krzysztof. “The Neoplatonic Roots of Apophatic Theology in Medieval Islam on the Example of Maqāmāt Aṭ-Ṭuyūr/Manṭiq Aṭ-Ṭayr (the Conference of the Birds) by ʿAṭṭār Nīšāpūrī (Ca. 1145–1221).” Verbum Vitae, 41. 3 (2023) 647–672.

Saebipour, Mohammad Reza, et al. “The Conference of the Birds: An Old Artistic Concept Making Sense in Modern Sciences.” Basic and Clinical Neuroscience Journal (2018): 297–305.

Salehi, Narges, and Mohammad Reza Haji Aqa Babaei. “An Analysis of the Concept of the ‘Other’ in Attar’s The Conference of the Birds.” Persian Language and Literature Quarterly Journal of Islamic Azad University 11.39 (2019): 120-138.

Wolpe, Sholeh. Attar, the Sufi Poet and Master of Rumi.

Influence on Later Authors:

Martínez, José Darío. “Borges and Farid Ud-Din Attar: The Influence of the Conference of the Birds on the Later Prose of Jorge Luis Borges.” UC Berkeley Comparative Literature Undergraduate Journal 3 (2012).

The above bibliography was provided by Daman Khalid (Washington State University).

“The Concourse of the Birds“, Folio 11r from a Mantiq al-Tayr (Language of the Birds). Painting by Habiballah of Sava Iranian

4 Conference of the Birds Images

The Conference of the Birds, A Solo Exhibition by Mohammad Barrangi

The Conference of the Birds, Group Exhibition by Tristan Hoare Gallery

The Bread of Mercy: An Illustration from the Mantiq al-Tair By Murad Mumtaz.

The above information was provided by Daman Khalid (Washington State University).

The Conference of the Birds, A Resonance Collective Production.

The Conference of the Birds by Fahad Siadat

The above information was provided by Daman Khalid (Washington State University).

The Conference of the Birds directed by Julie Portman

The World Stage Premiere of Attar’s Conference of the Birds.

Conference of the Birds directed by Wendy Jehlen

The Conference of The Birds,” at the Folger Theatre in Washington, D.C

The Conference of the Birds in Concert by Fahad Siadat

The above information was provided by Daman Khalid (Washington State University).

The Conference of the Birds by Jamal Rahman

The Long Journey Home | Attar’s “The Conference of the Birds” | Spotlight. A Perspective of Sholeh Wolpe.

Works that Shaped the World: The Conference of the Birds, A Lecture by Dr Milad Milani.

Life-changing power of Attar’s Conference of the Birds. Who are we? Where are we going? A Presentation by Sholeh Wolpe.

The above information was provided by Daman Khalid (Washington State University).