News & Events

Blazing New Epic Trails: In Celebration of Frederick Turner (1943-2025)

By Robert Crossley (University of Massachusetts Boston)

[Three-time epic poet, distinguished scholar and historian of global epic, and indefatigable advocate for epic in all its forms, Frederick Turner died in Dallas on September 4.]

I never met Frederick Turner in person—one of the regrets of my life—but he has been a presence in my life for forty years as a teacher of epic poetry, as a literary scholar, and as a writer. In the 1970s and 1980s I had been teaching an undergraduate course every three years or so on epic poetry. My students at the University of Massachusetts in Boston were an adventuresome crew—typically older, unprivileged, culturally diverse, nonresidential newcomers to literary study, but willing to try anything: the Iliad in translations by Robert Fitzgerald and Alexander Pope, Spenser’s Faerie Queene, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Wordsworth’s Prelude. Over time, the Homeric translations varied and became more colloquial (Robert Fagles, Stanley Lombardo, the fervidly faithless Christopher Logue). But something remained missing until in 1985 the distinguished Princeton Contemporary Poets Series published an epic poem set in the twenty-fourth century in the former “Uess.” When I discovered Frederick Turner’s The New World, I read it with a sense of both wonder and familiarity. Here was evidence that a literary form that I loved was not a museum-piece but a thrillingly living entity. It began appearing on my syllabus as my concluding example of epic poetry in English.

The truth is that I didn’t really know how to teach The New World. I had no difficulty with Turner’s invention of a hybrid form of science fiction and epic poetry. But Turner’s poem was as polymathic and encyclopedic as Paradise Lost and it had already taken me a decade to begin to figure out how to teach Milton. Although I didn’t do justice to The New World, I was convinced that my students needed to read it, needed to know that there was a living poet who had written an epic that was as rich and inventive as anything they were reading by Homer or Spenser or Milton. I continued to include The New World in my course as long as Princeton kept it in print. Surprisingly, a couple of years after introducing Turner into my epic course I was approached by a student whom I had never taught who asked if he could do an independent study on Turner’s second epic poem, Genesis (1988). Although some reviewers were skeptical of the strange futuristic poems Turner was producing in the 1980s, my own small corner of the universe provided evidence that an appetite for epic still existed—and that some readers were not only untroubled by, but were positively enthralled with, verse epics in science-fictional settings.

As those who use this World Epics website undoubtedly know, Frederick Turner has been a towering figure in the effort to restore visibility and stature to the epic form. The greatest living practitioner of the epic in English, he produced three major poems—The New World, Genesis, and the remarkable and strikingly innovative Apocalypse (2016, arriving two decades after the first two). These poems pioneered the future of America, the settlement of another planet, and the global crisis of climate change as fitting themes for epic treatment. They will constitute his legacy in literary history; their vitality and cultural relevance, as well as their startling originality in taking epic narrative into the future, will ensure that Turner’s work, like Virgil’s and Wordsworth’s, will outlive their author. His creative ventures have been complemented by the magisterial monograph Epic: Form, Content, and History (2014), the culmination of decades of his advocacy for the enduring presence of epic across time and geographical boundaries and for the formal beauty, the mythic grandeur, and the art of storytelling that epic exemplifies.

Turner’s three epic poems did not always get the respect of the academic and literary establishments. But Genesis, his epic about the creation of a living Mars, drew the attention of scientists and technology entrepreneurs interested in the planet’s future settlement. NASA appointed him as a consultant in their planning for extraterrestrial exploration. In the face of reviewers who dismissed his poetic techniques as old-fashioned, were confounded by his preference for long narrative poems over confessional lyrics, and considered his affinity for science fiction vulgar, Turner remained defiant. He was capable of using his linguistic facility as an instrument of savage indignation, as in this hilarious moment in Genesis where he enumerates in rhyming couplets the talents and credentials of a book reviewer:

First, a becoming modesty of style;

The aspirations of a crocodile;

A Shiite mullah’s open-mindedness;

A moral backbone of boiled watercress;

All the prophetic vision of a sheep

(But not so witty and not quite so deep);

A diction as unblemished by a thought

As is a baby’s bottom by a wart;

You stand in the traditions of our art

As a blocked artery in a dying heart.

If Turner had one overarching ambition as an epic poet, it was to return poetry to readers, stripping away the encrustations of academic posturing, theoretical navel-gazing, and postmodernist mystification. He wanted to recover what others regarded as the primitive virtues of poetry but which he considered its “classical” properties. He was uninterested, however, in empty nostalgia or the glorification of a narrowly defined European classicism. For him, “classical” art embraced certain poetic and narrative values that transcended cultures and times, and were rooted in the pleasures of formal structure, expected rhythms and delightful sound effects, engaged storytelling, didactic power, and intimations of the sublime. Epic offers fresh and challenging ways of seeing, understanding, appreciating, criticizing, and loving the world we think we know. In an essay on teaching the Bantu epic Mwindo, Turner celebrated epic narratives as “providers of coherent alternatives and scenarios whose exploration clarifies our picture of the world” (“To Drink from the Source: Teaching the Mwindo Epic,” in Teaching World Epics, ed. Jo Ann Cavallo, Modern Language Association, 2024, 249-57: 249).

None of this is to say that Turner’s epics are easy reading. They demand unhurried and careful attention; their allusions to other writers both inside and outside Anglophone epic literature are multiple. No poet writing in English since Milton has been so learned or has drawn on such wide-ranging disciplines in the structuring of epic narratives. Turner was conversant in neuroscience, archeology, evolutionary theory, landscape design, artificial intelligence, the history of philosophy, astrophysics, not to mention the literatures of a great many cultures and time periods. I often felt myself not fully grasping passages in his three epics—but this was no barrier to rapt enjoyment. I experienced the bewildering, beguiling pleasure I knew from reading James Joyce, listening to the later symphonies of Bruckner, watching the films of Fellini. I was in the presence of—and here’s another word appropriate to Turner but out of favor these days—genius.

In the early 2000s while working on a book about the cultural history of Mars, I came upon Turner’s 1979 novel A Double Shadow—a precursor to his great poem about the terraforming of Mars—and finally decided to get in touch with him. Our correspondence continued intermittently until this past summer, six weeks before his death. What I discovered through my email exchanges with Fred—as I learned to call him—was not just the erudite thinker of his scholarly publications and the brilliant master of iambic pentameter in his epics, but also an unfailingly generous and kind confrère, willing to share ideas with and offer encouragement to this unknown stranger a thousand miles away. When Fred sent me a draft of his third epic, Apocalypse, in 2014 and invited me to make suggestions as he worked on final revisions before its publication, I had the temerity to advise him to write footnotes to the poem to assist readers with some of the more abstruse concepts and terminology in the poem. For most contemporary poets and critics of poetry, footnoting is as anathema as rhyme or traditional metrical forms in poems. To my surprise, the published text of Apocalypse included a discreet set of endnotes of the very kind I had suggested.

While he was a fierce defender of his poetic practices and aesthetic principles, Fred was so humble and unassuming that I often felt both charmed and chastened by his graciousness. In the final communication I had from him, in July of this year, he reacted to a draft of my chapter on “Epic and Science Fiction” for Jo Ann Cavallo’s forthcoming Routledge Companion to World Epics: “The Epic/SF essay makes exactly the right bridge–I blush to have my work be one of the girders! Being with [Olaf] Stapledon, [Kim Stanley] Robinson, [Cixin] Liu and [Arthur C.] Clarke in the same text is an honor.” At the time, I had not yet read what he called his “mini-epic,” titled “Return”—an as-yet-unpublished Wordsworthian poem in nine parts and three thousand lines about the various “Freds” who emerged over the course of his life. In the days after learning of his death, I read this testament that traces his development as a writer and thinker and sums up his life’s work. And in one tersely-worded couplet, Fred articulated what I had labored to say in my entire essay about epics and the future: “The genre then was science fiction epic / (All epic truly SF, SF epic).”

Fred did not want his mini-epic to be thought of as an autobiography but as “a voyage / Of discovery, to find the secret source / whereby all language irrigates the world.” He loved language for its endless possibilities: how it could be played with, how it could be made into music, how it could dignify human longing and aspiration, how it could change the way people think, how it could embody and rejoice in beauty, and how it could create something from nothing. Nemo, the poet-narrator of Apocalypse, defined his work in this way: “The task of epic is to blaze new trails, / Mark territories so that others may / Explore and map them.” Or as Fred put it in “Return,” “For words have got a most miraculous gift, / To summon all the world to their command.” Fred Turner’s life and work were multifaceted and not easily summarized, but for those of us who care about epics and the future of epic, The New World, Genesis, and Apocalypse stand as hallmarks of the art of poetry—miraculous gifts that are cause for endless celebration.

***

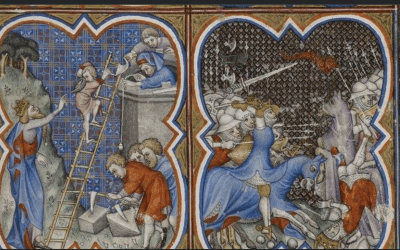

The image featured above is taken from the cover of Frederick Turner’s Latter Days (2022), published by the Catholic University of America Press. “Latter Days tells a story about the meaning of a human life in the strange new world that is emerging today.”

New epic poem wins science fiction award

Dave Jilk’s Epoch wins Colorado Authors League Science Fiction Award for 2025.

On July 13, 2025, the Colorado Authors League (CAL) awarded its prize in Science Fiction to Dave Jilk’s Epoch: A Poetic Psy-Phi Saga. This 2024 epic poem, with its diverse forms and a non-human heroic protagonist, was selected over other works written in the conventional science fiction prose novel format. Founded as an organization of professional writers, CAL has recognized works by Colorado-based authors across multiple categories and genres since 1942.

See Frederick Turner’s reflections on Epoch on the World Epics website: https://edblogs.columbia.edu/worldepics/project/jilk-epoch-a-poetic-psy-phi-saga/

CFP: Epic and Destiny (AOQU)

Call for papers for the upcoming issue of AOQU dedicated to Freedom and Necessity of Heroic Action between Antiquity and Modernity. English version below. Italian and French versions on the AOQU website: https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/aoqu/call-for-paper

«AOQU» VII, 2 (2026)

Epic and Destiny. Freedom and Necessity of Heroic Action between Antiquity and Modernity

Edited by Gabriele Bucchi and Corrado Confalonieri

The 2026/2 issue of AOQU seeks to investigate the multifaceted relationship between freedom and necessity—understood also as individual and collective destiny—in the actions of characters within heroic narratives from antiquity to the present day.

Epic narratives, like all plots, are structured around a transition from one state of equilibrium to another, often through one or more “reversals” (Aristotle, Poetics 6, 1450a). These narratives are typically oriented toward the realization of a final goal—a telos—which the characters’ actions tend to fulfill, though not without ambivalence and conflict. Depending on their role within the plot—whether as central heroes or heroines, or as secondary figures—characters engage with their own destiny and that of others in different ways. Sometimes they consciously cooperate with what has been foretold by a higher power (be it the gods, fate, History, or Providence); at other times, they resist or attempt to delay its fulfillment, and in some cases, they even seek to escape it altogether, through flight or suicide. The tension between freedom and necessity in both ancient and modern epic invites analysis not only of narratological aspects—such as narrator omniscience, character self-awareness, and the relationship between the main plot and episodic structures—but also of the epic’s relationship with other genres, particularly tragedy. According to a well-known formulation by Hegel, the distinction lies in the nature of agency: a dramatic character “creates his fate himself, whereas an epic character has his fate made for him, and this power of circumstances (die Macht der Umstände), which gives his deed the imprint of an individual form […], is the proper dominion of fate” (Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Arts, ed. Knox).

This issue invites contributions that explore how the relationship between epic and tragedy has been interpreted across different historical periods—and in the corresponding literary theories—in relation to the freedom and necessity of action. Of particular interest are the types of characters through which this relationship is articulated, and the narrative forms it assumes, including narrator interventions, character monologues, and dialectical confrontations between characters. The issue therefore welcomes contributions that examine, through significant works from the epic canon or texts more broadly inspired by the epic form, topics including but not limited to:

– The configuration of the relationship between characters and destiny—and, consequently, the interplay between the voices of the characters and the narrators;

– The relationship between epic and tragedy, both in canonical texts and in the philosophical and aesthetic reflections of modernity (18th–20th centuries);

– The use of epic poetry within philosophical-theological debates on conceptual dichotomies, such as free will and divine foreknowledge, Fortune and Providence, individual passions and collective interests (e.g., Nation, State, ideologies);

– The emergence of character resistance to higher forms of determination—whether embodied by God, the gods, or analogous figures;

– The reconfiguration of the idea of destiny in modern literary forms directly inspired by the epic tradition (including rewritings, parodies, adaptations).

Submissions must be entirely unpublished and may be written in Italian, English, or French. Proposals (maximum 350 words) should be sent to gabriele.bucchi@unibas.ch and confalonieri@chapman.edu by September 20, 2025. Notification of acceptance will be communicated by October 20, 2025, and final submissions are due by May 20, 2026.

Letteratura cavalleresca italiana / Italian Chivalric Literature

Call for papers for the 2025 issue (the deadline to send proposals is July 21, 2025): https://www.italianisti.it/news/call-for-papers/cfp-volume-vii-2025-letteratura-cavalleresca-italiana

“Letteratura cavalleresca italiana responds to the desire to establish a cultural and academic arena in which to examine the specific literary subject indicated by the journal’s title, whether in poetry or in prose, and including Franco-Italian literature, composed in the centuries ranging from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. The term ‘Chivalric Literature’ means those works written to exalt the ideals and virtues of knights, be they members of King Arthur’s court or the paladins of Charlemagne, as well as the heroes and anti-heroes of other literary traditions in which knights and chivalry itself become the object of praise and respect or of jokes and ridicule. Therefore the journal will concern itself not only with those Arthurian romances, largely of French origin, and with the great Renaissance epic poems of Boiardo, Ariosto and Tasso deriving, for the most part, from Carolingian material, but also with the cantari on chivalric themes, with the Franco-Italian chansons de geste, with mock-heroic and satirical poems from Pulci to the Nineteenth Century, including Leopardi’s Paralipomeni.”

A Yearly Journal * Fascicoli / Issues*

Founded by: Christopher Kleinhenz, Davide Puccini

Editors-in-Chief:

Maria Cristina Cabani (Università di Pisa, Italia), Maiko Favaro (Università di Roma La Sapienza, Italia), Giorgio Forni (Università di Messina, Italia), Davide Puccini (Piombino, Italia), Renzo Rabboni (Università di Udine, Italia), Christian Rivoletti (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Deutschland)

Advisory Board:

Matthias Bürgel (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Deutschland), Anna Carocci (Università di Roma Tre, Italia), Alberto Casadei (Università di Pisa, Italia), Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University, New York, USA), Corrado Confalonieri (Chapman University, Orange, USA), Francesco Lucioli (Università di Roma La Sapienza, Italia), Eleonora Stoppino (University of Illinois, Urbana, USA), Franca Strologo (Universität Zürich, Schweiz), Matteo Venier (Università di Udine, Italia), Juliann Vitullo (Arizona State University, USA)

Guarantee Board:

Gloria Allaire (University of Kentucky, Lexington, USA), Albert Russell Ascoli (University of California, Berkeley, USA), Cristina Barbolani da Montauto (Università Complutense, Madrid, España), Daniela Delcorno Branca (Università di Bologna, Italia), Christopher Kleinhenz (University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA), Antonio Lanza (Università dell’Aquila, Italia), Leslie Zarker Morgan (Loyola University of Maryland, Baltimore, USA), Maria Bendinelli Predelli (McGill University, Montréal, Canada), F. Regina Psaki (University of Oregon, Eugene, USA), Paola Vecchi Galli (Università di Bologna, Italia)

Double blind peer reviewed articles are published. The reviewers are absolutely independent of the authors and not affiliated with the same institution.

More information available on the Letteratura cavalleresca italiana website.

Multimedia Collection of Philippines Epics and Ballads

After four years of silence, this Epics and Ballads Collection that has been built up in collaboration with several National Cultural Communities of the Philippines and in their home land has been upgraded, emulated in 2023-2024. It has been enriched with many videos and provides complementary documents in PDF contextualizing and analyzing the sonic compositions by the very people involved in this research since 1990.

The website reconstruction is in line with the original information structure and approach, but using today’s technology. The collection of epics and ballads allows the public to listen to 16 indigenous languages and epic poems from various areas of the Philippines in relation to the now established texts in PDF.

This collection consists of 240 Audio-tapes, 53 CDs, 3 Hard Disks; 8,091 pages of Texts phonemically transcribed in 16 vernacular languages then translated to English, or Tagalog or French. The16 National Cultural Groups involved in this safeguarding are: Ifugao, Sama, Tausug, Tagbanwa, Tala-andig Bukidnon, Manobo, Kalinga, Ikalahan, Mamanwa, T’boli, Itneg, Tagalog, Maranao, Sulod Panay or Panay Bukidnon, Palawan, and Tao.

The texts of the narratives are bounded in 34 printed volumes; a gallery of 2028 Photos with captions, 74 articles in English and 54 Videos complement them.

This physical archive is housed and safeguarded at the Pardo de Tavera Special Collections of Ateneo de Manila University, Rizal Library, in Quezon City and accessible for consultation in situ as well.

The files of the Collection are presented as is, to enable researchers to analyze and process the content using their own resources.

You can register at the following website: epics.ateneo.edu

After registration, the website is accessible on most modern web browsers on both Mac and PC operating systems. It is also accessible on a mobile device such as a smartphone or tablet, running iOS or Android. The mobile version of the site may look and function differently, because the design elements adjust for smaller screens.

You can also download the poster in PDF for more information.

The following issue of Ateneo Magazine gives more information about Dr. Nicole Revel’s work in documenting oral epics in the Philippines (pp. 22-25): https://heyzine.com/flip-book/AteneoMagazine2.html#page/1

Camões: No poet is an island

The Legacy of Luís de Camões: Portugal’s Greatest Poet.

The Hispanic Museum & Library

A symposium taking place on October 1st that aims to show that this famous poet — a symbol of a changing world – spoke to all eras and that his words deserve global recognition. Contextualizing Camões offers an opportunity to delve into the cultural dynamics of the sixteenth century and to highlight the significant contributions of European humanists and artists during this fascinating period.

The invited guests are:

- David Kenneth Jackson, Lecturer in Portuguese at Yale University

- Joaquim Oliveira Caetano, Director of the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (Portuguese Museum of Ancient Art)

- Josiah Blackmore, Chair Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Nancy Clark Smith Professor of the Language and Literature of Portugal

- José Miguel Martínez Torrejón, Distinguished Professor at Queens College

- Isabel Almeida, Associate Professor Faculdade de Letras, Lisbon University

- Henrique Leitão, Provost and Senior Researcher, University of Lisbon

- The symposium will be held on October 1st from 10 am to 5 pm, featuring morning and afternoon sessions that conclude with a lively debate and Q&A

For more information, visit https://hispanicsociety.org/exhibitions/future-exhibitions/the-legacy-of-luis-de-camoes-portugals-greatest-poet/

Italian Chivalric Literature and Digital Humanities – Two Guest Lectures

Now hybrid event, Zoom link at bottom

Guerres d’émotion : la chanson de geste et les affects (CFP)

“Hacer dragones y serpientes para este teatro”: los libros de caballerías y la comedia del siglo XVII

This conference (in Spanish) on books of chivalry and comedies of the 17th century is part of the Historias Fingidas International Seminar (2022).

It will take place November 10-11, 2022, at the University of Verona, Italy, and can be followed online.

The program and zoom link can be found here.

Calls for Proposals: RSA San Juan 2023

Renaissance Society of America members can post calls for papers and seek participants for sessions in all disciplines to be held at RSA San Juan (9–11 March 2023). Session proposals are welcome in the following formats: Paper panels; Seminars; Roundtables; Workshops. Papers can be in English or Spanish.

For more information, see the Calls for Proposals: RSA San Juan 2023 and RSA Annual Meeting Submission Guidelines.

Story-telling Fellowships at University of Toronto Scarborough

Three University of Toronto Scarborough students are reimagining an ancient Tamil epic thanks to an inaugural U of T Scarborough Library Sophia Hilton Storytelling Fellowship.

This year’s fellowship from the Sophia Hilton Foundation focuses on the Tamil epic The Legend of Ponnivala Nadu, translated in Brenda Beck’s forthcoming English edition as The Land of the Golden River. The students will be creating a series of podcasts. For more information, go to Rebecca Mangra’s January 27, 2022, University of Toronto announcement.

Symposium: Music and Epics

From 2 to 4 November 2022, a symposium will be held in Geneva on the theme of the Epic, focusing more specifically on the role of music in its interpretation. Based on an idea of the Ateliers d’ethnomusicologie (ADEM), in collaboration with the Haute Ecole de Musique de Genève (HEM) and with the contribution of the Séminaire nomade de la Société Française d’Ethnomusicologie (SFE), it will be held within the framework of the festival Les nuits du monde (ADEM), which is based on the same theme. The primary motivation of this vast project is to connect live performance, educational activities, scientific research and publication. A selection of the contributions to the colloquium will subsequently be published as a dossier in the Cahiers d’ethnomusicologie (Vol. 37/2024). Artists, researchers and students of music or (ethno)musicology interested in participating in the colloquium are invited to submit their proposals before 15 January 2022.

For more information, see: https://adem.ch/en/evenements/music-and-epics

World Epics in Puppet Theater: India, Iran, Japan, Italy

The World Epics in Puppet Theater: India, Iran, Japan, Italy project consists of scholarly encounters and puppet theater performances designed to foster intellectual exchange and public awareness about four epic traditions and their continued elaboration in puppetry arts. It also aims to feature contemporary puppeteers who use the dramatic capabilities of theater to present, question, and reinvent epic narratives across languages, cultures, religions, and territories.

The project is part of the Columbia University Humanities War & Peace Initiative, which “fosters the study of war and peace from the perspective of scholars in the Humanities, in conversation with colleagues from around Columbia and the world […] with an ultimate goal of perpetuating a more peaceful world.”

Academic committee: Jo Ann Cavallo (Columbia University), organizer; Olga M. Davidson (Boston University); Claudia Orenstein (Hunter College, CUNY; UNIMA-USA); Elizabeth Oyler (University of Pittsburgh); Paula Richman (Oberlin College); and Poupak Azimpour Tabrizi (University of Tehran, Iran).

Co-sponsors of the mini-symposium: the Humanities War and Peace Initiative, through the Division of Humanities in the Arts & Sciences at Columbia University; the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture, Columbia University; the Museo Internazionale delle Marionette “Antonio Pasqualino” in Palermo, Italy; the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, University of Connecticut; the Puppet Arts Program, Department of Dramatic Arts, University of Connecticut; the University of Pittsburgh; and UNIMA-USA.

For the latest information about the project (including videos of the mini-symposium, the Q&As with the puppeteers, and select performances) as well as further suggested resources, see the World Epics in Puppet Theater project page.

World Puppetry Day – UNIMA

World Puppetry Day 2021

World Puppetry Day takes place annually on March 21. Click here for this year’s World Puppetry Day events worldwide.