by: Cindy Gaeun Choi

GINGER AND BEESWAX

Date: Mar 10 2018

People Involved: Myself

Location: Elliott Hall Lounge and Kitchen

Environmental Conditions: Dry, nighttime, no sunlight.

Purpose of Ginger: Heated ginger used to treat stomach ache, vomiting, diarrhea, and rheumatic pain

Purpose of Beeswax: As the structural holder, as well as the fundamental function as a skin protection and moisturizer.

Why I chose these three ingredients and what I predict will happen: Ginger is very commonly known as an ingredient that aids digestion, specifically relieving nausea. In the tacit knowledge sense (Grandmother’s recipe), ginger additionally is effective at relieving pain in the throat when someone has a cold. Thus, as a food that tackles both the digestive and immune systems, I thought it appropriate to see how beneficial it would be as a buffer between the moxa plant and the human stomach. Thus, the source of this recipe is both the news article as listed below and my understanding of the ingredient.

Process: Ginger cut horizontally, so that each piece could layer on top of each other. I was not sure where to begin, or even how much ginger to use. I was unsure of how much beeswax I needed as well. There were no measurements nor telling of how big the final contraption should be. I estimated through taking into consideration how big the actual moxa mixture ordered is (18 x 200 mm) and decided that, then, the contraption should be at least able to hold this circular mixture on top.

I then took the cut up portions of the beeswax to the kitchen in order to make the shape of the beeswax circular. I was not sure how to mold the beeswax, and decided to simply use my pan and melt it just as I would chocolate.

I first simply placed the beeswax in the middle of the pan after I heated the pan at the highest possible level.

Almost immediately, the beeswax began to melt. It did not even soften first, which I thought would happen. I imagined the wax to soften, so that I could quickly take it out of the pan and mold each piece together into a circular shape in my hands or with a spoon in the pan. However, I was obviously wrong, and forgot that it was wax and that the middle step of softening would only happen with ingredients such as chocolate, which I was comparing this to.

I decided to let the fire going, except turned the heat down to a level 1 rather than at the highest level in order to let it “simmer,” which also did not happen. The beeswax simply continued to melt into liquid form, quite rapidly too. One good thing about this process was that it gave me the opportunity to truly mix all pieces together, without any bumps, literally. However, because this is not what I had expected to happen, I just let the material melt, rather than trying to fix it and cool it off into half-solid and half-liquid.

After about two minutes, all pieces had turned into liquid, except for the two pieces that I had been touching with my spoon. This is because the spoon was not being heated directly as the pan was, and so every time I tried to stir the “pieces (now liquid, indistinguishable as independent pieces)” some residue would stick onto the spoon. Deeming that there was excess of beeswax for just the one contraption, I took the two mildly soft pieces out of the pan.

As soon as I had finished taking the two pieces out, I needed the liquid beeswax to become solidified again to a certain extent so that I could take it out of the pan and into my hands or another plate. I remembered that since it is a form of wax, if I put cold water on top of this liquid, the two liquids would not mix, but instead simply help the beeswax come back into the solid form. I was right. When I poured cold water around the pan, the liquid beeswax immediately went from completely clear oil to the beige yellow solid colour again. Afraid that it would just stick to the pan as a solid form, I quickly poured out the cold water and began scraping the mixture out into my hands. Thankfully, the mixture was not hot enough to burn my hands, though the pan was still quite hot.

The ginger dried up overnight and this was the final product. The ginger felt dry but not brittle. The smell definitely was still very strong. Because the herbal moxa mixture has not yet arrived I was unable to see how it would fit atop this contraption. However, just by looking at this, I could say that it would not be stable or steady. There is nothing connecting the ginger pieces and the beeswax base. I will retry the ginger and beeswax ingredient contraption later with a sort of connecting factor, such as honey or vaseline, after I experiment with all the other ingredients as well. The experiment itself took about an hour but I had left the ginger to dry overnight because it was very wet and I was not sure how the heat would have reacted to this dampness.

Questions: With the second journey, I was a little more expectant of how to proportion my ingredients; a little smaller than last time. It was harder for me to work with smaller ingredients, but I felt that making the buffer bigger would only interfere with the medicinal benefits. Additionally, making the buffer bigger would also mean more ingredients, which would ultimately be wasted because the medicine would not be utilising the excess in order to burn itself and heal the patient. At the same time, some questions that arose were how did placing these pieces of garlic atop beeswax completely mesh and intermingle for the medicine to receive in equal parts the benefits of both ingredients? Was the beeswax even necessary? Could the moxibustion medicine be placed directly on top of the pieces of ginger? Or would direct contact with the spicy and potent ingredient be too much? I could definitely see ginger being “too much” to deal with, especially for someone with an already weak immune or digestive system. That led me to a bigger question of what kinds of bodies work best with what ingredients? Is it best to simply choose the ingredient with the most benefits, or should we be selecting these ingredients in steps, as a progression? This reminded me of a quite specific part of Pang’s article, where he speaks about the difference between artisanal skill and aesthetic sensitivity. It reminded me of the battle between what is best fit for one versus what is regarded as the best. Who is the ultimate decider? Would the doctor simply prescribe the most average solution? Is that fair to the patient, if he had opted for “aesthetic sensitivity?”

SALT, PEPPER, AND BEESWAX

Date: Mar 11 2018

People Involved: Myself and Emily Woo (took a picture of me, but did not directly get involved with the making process)

Location: Sulz Tower Kitchen

Environmental Conditions: very bright day, pretty dry (heater was on), big windows, no wind.

Purpose of Salt and Pepper: “This method of moxibustion is known to be effective in treating abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea, pain around the umbilicus, pain caused by a hernia, and prolonged dysentery. It is also effective in restoring Yang from a state of collapse, where symptoms of excessive sweating, cold limbs, and undetectable pulse may manifest.”

Purpose of Beeswax: Structural support and moisture retention.

Melting the beeswax in a different way than last time, as melting it in the pan did not seem to work as efficiently or effectively as I would have liked. Scrubbing the wax off the pan was especially painful and solidified my doubt that heat on the stove and cooking utensils was not the right way to melt beeswax. Thus I decided to melt the beeswax through natural sunlight and glass, just like the old school science experiments.

Seeing as how thick and viscous the beeswax is, the chunk did not melt like it had in the last process. This was a good sign towards progress, as I did not expect beeswax to melt into liquid so quickly. Instead, I wanted to mold with my hands a material that resembled hard or soft clay.

A close-up shot of how I was concentrating sunlight onto my beeswax chunk. This method was actually quite effective, but not as efficient as I had hoped for it to be. The flat piece that is not receiving the concentrated sunlight is the piece that I had already taken off from the main chunk. I checked to see if the chunk was ready to be molded into a flatter piece, but found only a portion of the chunk to be available. Thus, I took the piece that easily came off as soft and ready to be molded and just flatted it out into a circular shape. I then kept going with the same process of concentrating light and taking small portions out and molding them.

After about 25 minutes, I had enough portions of the main chunk to have a solid beeswax base. This base definitely seemed more durable than the base from the last procedure. It also was made easier and safer, with less unexpected outcomes. I patched each portion up together to create on big circular base. It was very easy to work with, because all pieces were still warm and moldable. I decided to do this under the sunlight and then take into the shade once I was satisfied with the size of the base, again according to the size of the actual herbal medicine that would be used on top (18 x 200 mm).

In the middle of the base, I placed another slightly thicker, slightly smaller piece of beeswax to separate where the salt and pepper should go. It was also in order to recreate the look of the modern day indirect moxibustion stick that I had designed in my field note number two.

Because the raised platform was too small, it was quite difficult for me to get the salt to stay within the boundaries of the platform only. I tried to scrape off the excess around it with my knife and cleaned it out.

This video shows me tapping the pepper on the salt and contraption very carefully. Because the salt had gotten everywhere, I made sure to take this step even more slowly for the pepper.

This video shows me pouring the honey. This was never intended to be a part of this journey. However, I found that every time I even lifted my hands from the mixture of salt and beeswax, the salt would be displaced and I would not be able to move it to anywhere along the plate, much less onto my stomach. Thus, after the pepper had been sprinkled, I decided to add the runny honey for support and complete mixture of the two ingredients with this third.

This is the final product. As shown, the salt and pepper had been displaced many times throughout the process to the sides. It was definitely one of the harder processes and ingredients to work with. My thumbs were aching from molding the beeswax, and thus it made it harder to concentrate on the smaller areas of the salt and pepper.

Reflection and Questions that follow: If my first and second journey were about questioning the ingredients and their properties and how they would work to benefit our bodies, this third journey was more about the actual contraption themselves. I sincerely wished to improve the contraption and make them look “legitimate.” I also wondered why I was basing my contraptions on beeswax other than the fact that it was the structure-holder. Instead of using the material at hand, perhaps I could work on finding a substitute for ceramic that I could simultaneously mold myself. Another way I could improve my constraption is by looking at how I begin to mold my objects. The last time was through my pan and direct heat, this time was through natural sunlight and concentrated glass.

BEANS, GARLIC, AND BEESWAX

Date: Mar 10 2018

People Involved: Myself

Location: Elliott Hall Lounge and Kitchen

Environmental Conditions: Dry, no sun, nighttime.

Purpose of Garlic: used to treat respiratory disorders

Purpose of Black Beans: Filled with fiber and potassium, these beans are supposed to lower cholesterol and decrease risk of heart disease.

Purpose of Chilli Beans: Nutritious in that it includes a lot of antioxidants and fiber which all promote health.

Purpose of Green Beans: Good source of calcium, iron, and potassium.

Purpose of Beeswax: As the structural holder, as well as the fundamental function as a skin protection and moisturiser.

Why I chose these three ingredients and what I predict will happen: I chose to start this journey with garlic because it seemed like the most widely used, and most widely referenced ingredient. I also chose the three beans because it was the most unheard of food in the context of my experience with herbal medicine and moxibustion. Nobody ever mentioned avoiding (pork and certain types of bean sprouts are told to be avoided) nor actively seeking (warm foods are generally recommended for people with weak bodies) beans. The combination of the one ingredient that made most sense to me and the ingredient that seemed most silly to me intrigued me to see how the two could mingle.

Picture of the ingredients: black beans, green beans, chili beans, three peeled cloves of garlic, and a cut portion of beeswax. As this was the first mixture I was working with, I wasn’t sure how to portion any of the ingredients.

I started mashing the three types of beans together. The black beans and chili beans worked well together and I was able to get the consistency that was instructed. When I tried harder to get the green beans to be mashed into similar consistencies, it did not work. Instead, they broke up into rigid pieces. I could tell it was not going to smoothly be integrated with the other two types.

In order for the consistency to be like the korean rice cakes (떡국떡) I made the ultimate decision to take the green beans out. Then I continued to mash the black beans and chili beans together to create an even surface. I also took out any of the outer layers that were starting to peel off of the chili beans.

After the beans mixture had gotten to the correct consistency in my opinion (which was in comparison to the 떡국떡 I had eaten all these years) I began working on the garlic and mashing one of the cloves first with the spoon I had used for the beans.

The spoon obviously was not the best option to mash the garlic into a consistency close to that of minced garlic. Thus, I decided to experiment with three different types of knives. I wanted to see which one would hold best to achieve the consistency of the beans and which knife would allow the garlics to be integrated within the mixture as moosthly and equally as possible, without becoming as small and diced as the store-bought minced garlic (I felt the need to be particular with the consistency of these ingredients not because I was told to but because it only seemed appropriate for all the ingredients to be naturally and smoothly coexisting as one mixture rather than as separate entities).

I moved on to the plastic knife, which was the only knife with the rugged edges. I decided to try it with a lot of doubt, and sure enough, it failed me. I moved onto the silverware knife, which was a little sharper but still not enough to allow an even cut with every press down into the clove. I finally settled with the ceramic knife, which I knew I was going to resort to, because I had always used this knife in order to get my ingredients cut without much effort but with great smoothness and evenness. I also began to cry at this stage. Peeling and cutting garlics into big pieces was one thing, but working with them for an extended time really pinched my eyes and nose to the point where tears rolled down.

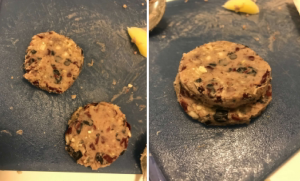

I divided both mixtures into half, because I needed two layers for the contraption to look like the one from Field Note 2.

I then mashed each respective pile with their halves. After mashing them, I shaped them into circular forms to prepare them for the final look. I carefully took the smaller half and placed it atop the bigger circle. It looked pretty convincing to me to be used as a buffer between the medicine and the human skin. However, the look was not yet complete. I took my spoon one last time and dug a slight indent in the middle of the smaller mixture in order to create a space for the medicine to stay atop.

I ended up not even having to use the beeswax as the structural holder. Once the beans had been mashed up together, it was obvious that the contraption was going to be stable on its own. Thus, I saw no need to place it under the beeswax or keep it surrounded. Instead, I decided to let the mixture dry to solidify. However, because these were raw ingredients that had been exposed to air and moisture, I put the mixture in the fridge. I did not want them to get crusty or moldy. The beans all mashed up together did smell a little funky and I was sure I did not want to spend more time with these materials in its wetness. I would wait until they were less “raw” and more “settled,” or dry. The entire process took about an hour and when I try this again when my actual medicine comes, I intend on drying it for about two hours, depending on the density of the beans mixture and how thick it is.

Reflections and Questions that follow: From this first journey, I found myself very confused yet innovative at the same time. I was sure I was not doing everything correctly, starting from the aspect of proportions, size, how much to mash them, how long I should wait to move onto the next step, and many more logistical questions in between. However, when I found myself stuck and clueless, I forced myself to think in the most logical sense I could. To me, that was simply going by the look of the indirect moxibustion stick and bowl contraption I was exposed to. I thus found myself asking what difference would it make for me to be making my contraption this way versus the function of the bowl that Dr. Jung used for me at his hospital? If efficiency was not a factor at Dr. Jung’s hospital, would he have opted for this bowl made completely of raw materials? Is the ceramic bowl just for convenience and commercialisation of this herbal practice? If I were able to find a way to mass produce this kind of contraption on a daily basis, would it prove to make a difference? From the brief interview I had with Dr. Jung, I think he would say that it could make a difference in the long run, when the moxibustion is done every day for at least two weeks (he emphasized that two weeks would be the minimum days needed in order for our bodies to fully adjust to the medicines that were being implemented through these medicinal herbs). However, with patients who are looking for a quick stomach or back relief for the day, it would not pose any greater benefits. This journey relates to the articles by Liu and Frumer about the significance of tactile knowledge and the physicality of an object in of itself. It really forced me to think about what the actual objects would mean in terms of healing and benefits. Each ingredient was obviously chosen for a different purpose, with intentions and consequences that had been thought through in terms of their own “genetic makeup.” Liu also speaks about the concept of objects as “tokens,” especially the translated objects as such. This makes me wonder about the history of each ingredients and how ingredients such as beeswax were imported into East Asia from South Asian countries. Would the intentionality change based on where the ingredients originated and where the ingredients were used, and for whom? This additionally gets into the argument that Mukharji articulates about an identity of an object changing based on origins.