For this project, I sought to answer the question, “What makes my body mine?”

I investigate religious shame, dysphoria, and dysmorphia through self-portraiture to convey how aspects of identity shape how I present and perceive myself (both integral to my conception of embodiment and selfhood), respectively depicting each from left to right. My aim is to demonstrate how the body is shaped by external forces of power: as for religious shame, this translates into institutionalized religion; for gender dysphoria, heteropatriarchy; and for body dysmorphia, fatphobia stemming from late-stage capitalism. Having created these self-portraits with this intent behind them, I am recognizing how I have internalized the effects of these systems and ‘live them out’ in my presentation and self-perception. I want to demonstrate that a greater sense of wholeness and autonomy can be gained by holding space for these difficult relationships between institutionalized power and the body; these each operate on deeply subconscious levels, and by recognizing that they exist, we can better identify what aspects of self-expression are compulsive and which deeply resonate with us. What makes my body mine is a reclamation of the religious shame, dysphoria and dysmorphia that has ruled my relationship to my body, of dredging up the uncomfortable and unpleasant and deciding how it’ll shape my future self.

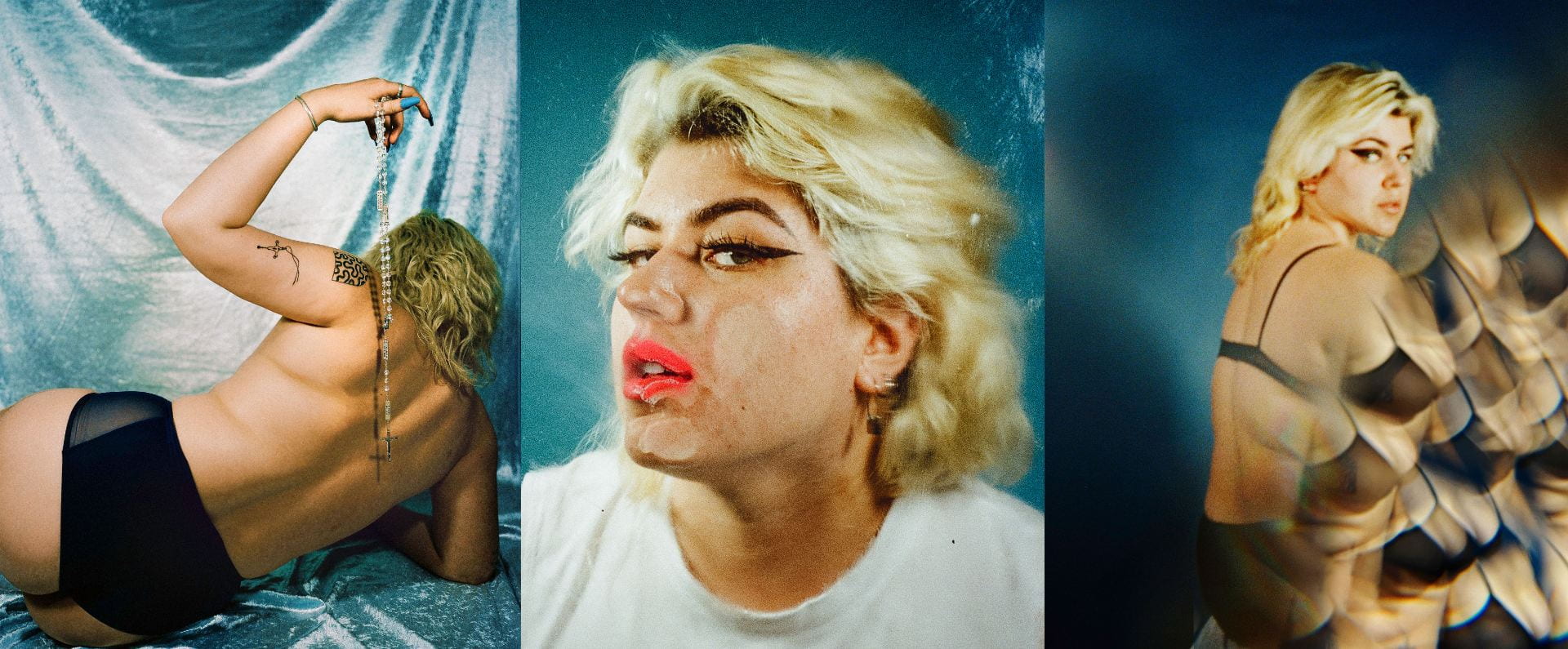

Religious Shame

In my first self-portrait, I draw from Donovan Schaefer’s Religious Affects with the intent to display how religion circulates images and affects that ultimately transform the body. Throughout my fifteen years engaged with the Church, Catholicism had denied me of an autonomous relationship to my body; rather than it being my own, it was the property of God. The shame I felt in experiencing sensations that were not immediately oriented around piety or sacredness laid the groundwork for a dissociated relationship to my body and tinged these experiences with guilt.

In the first self-portrait, I am depicted with my exposed back to the camera, a rosary draped over my shoulder. By juxtaposing nudity with the imagery of the rosary hanging above my body, I am attempting to visually represent a reclamation of the shame I had experienced around my body within the Church; the contrast itself is intentionally unnatural based on ideas of what is religiously ‘acceptable.’ I want to draw attention to my posing in particular. Despite the appearance that this position is natural, it was extremely painful to maintain. This is precisely how religious affect can operate: by invoking affective responses to certain religious images (i.e. the rosary) which are imbued with power, the body then conforms to recirculate that power amongst other bodies. While conformity and belonging—maintaining ‘naturality’— is initially appealing, it can be distressing to uphold. Religious affects shape the body through emotion like guilt, which then prompt the body to move and present itself in specific ways.

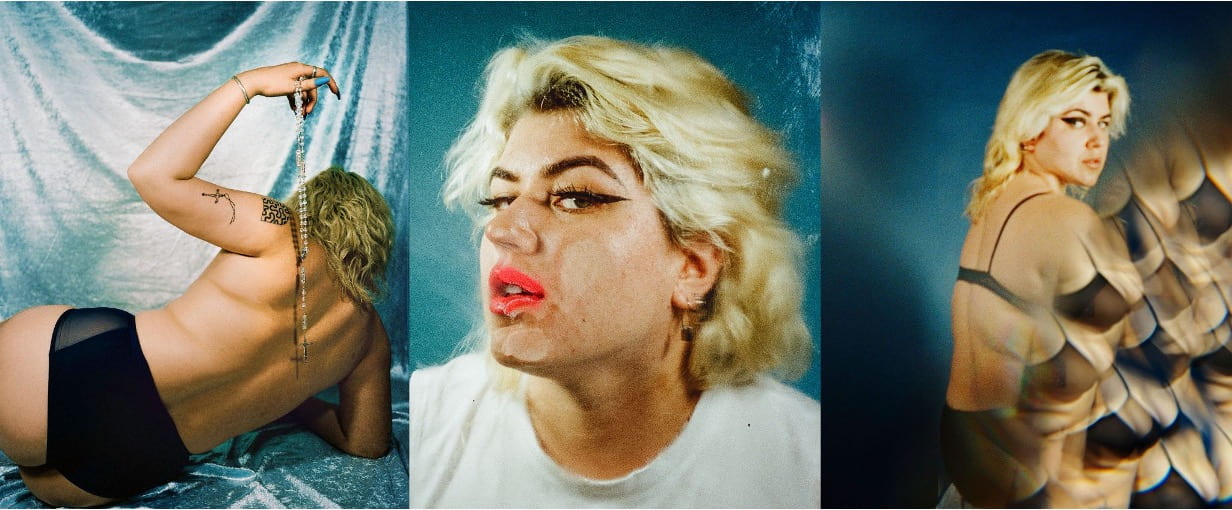

Dysphoria

The second self-portrait is a visual representation of dysphoria drawn from Gogol’s The Nose. The Nose pertains to dysphoria in a broader scope, whereas I focus on my experience with gender dysphoria in particular. In The Nose, Kovalyov’s identity and the pride he carries with it are based so heavily on his appearance that when he loses his nose, he is devastated by this change and his demeanor completely shifts. As for myself and my relationship to gender dysphoria, to be constantly externally perceived as a woman as a result of heteropatriarchy and society’s desire to adhere strictly to the gender binary when I do not claim that identity obscures my self-perception. On one hand, I am self-assured in my queerness—I know I am not a woman—but on the other, I experience intense dysphoria when assumptions are made about my gender based on my appearance because I have inevitably internalized a desire to be understood and, thus, to conform. This incongruence is where my discomfort with my gender lies.

In this self-portrait, I’ve conventionally ‘feminized’ my appearance with false eyelashes and bright lipstick. My face is pressed up against a glass pane to reflect the essence of external perception; I am taking ownership over my appearance as a ‘woman’ by demanding to be seen as such, yet this is explicitly on my own terms. There is a dissonance between my everyday appearance and what is depicted here, but I find solace in being able to play upon the discomfort I feel when misgendered and claiming it, perhaps even playing with it in the process.

Dysmorphia

The last self-portrait in the triptych is demonstrative of body dysmorphia, touched upon in Cortazar’s piece titled Letter to a Young Lady in Paris. In the short story, the unnamed narrator vomits up what seem to be benign bunnies that eventually destroy the apartment in which the narrator resides, formulating an allegory for bulimia. What appears to be appealing is, in reality, a force of destruction that totally distorts reality and induces harm for the sake of ‘beauty.’ Although Cortazar does not make a connection between body dysmorphia and/or disordered eating and the internalization of fatphobia’s effects on bodily self-perception, I tie them together for the sake of my own personal experience. For example, in relying heavily on social media, I—like my peers—are constantly marketed products to make ourselves more ‘beautiful’ (or, really, thinner), however, this comes at a quite literal financial cost and takes an emotional and societal toll, too. Fatphobia is inextricably linked to late-stage capitalism which denotes that only certain thin bodies are desirable and therefore valuable, constructing a system where those who inhabit bodies that fit outside of that category must be changed to fit normative ideas of worth, while simultaneously generating profit or are otherwise deemed disposable. Fatphobia makes non-thinness so threatening that it highlights a perceived ‘flaw’—in this case, weight gain—that is otherwise unnoticeable to others and distorts self-perception, resulting in body dysmorphia.

For me, body dysmorphia manifests itself in my inability to know what my body ‘truly’ looks like, which I’ve reflected in the triptych’s last self-portrait. My face and part of my body are visible, while my stomach is obscured by fractal images which I achieved by shooting through a prism. This distortion is reminiscent of the experience of looking into the mirror and being unable to discern what my appearance really is. In recognizing that what I am experiencing when I look at my body is indeed an augmentation of reality, I can observe my appearance without negative judgment. By taking control over disorienting thoughts that can accompany the experience of body dysmorphia, I feel like my body is truly mine.

Artist Biography: Caitlyn Stachura is a junior at Barnard College studying Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies with a minor in Religious Studies. In art and their academic studies alike, they seek to explore the relationship between sex, the body, and religiosity.