C. Some Inupiat Contexts

Who are the Inupiat?–Cannelle Bruschini with Elizabeth Hutchinson

The Inupiat are a group of Inuit, Alaska Native people organized into autonomous villages with historical, cultural and linguistic ties. Their traditional lifeways include hunting, fishing and gathering, all of which continue to be practiced. (Burch 2006, 24) The word Inupiat is formed of “iñuk,” which means “person” and “-piaq” meaning “real” or “genuine.” The combined meaning is thus “real people.” (Alaska Native Language Center)

The Iñupiat live in “eight regional ‘nations’, each containing one large village.” The villages vary in size. Some of them contain a few families whereas some of them are larger, consisting of many family groupings. The differences between the dialects, the clothing and the rituals enable to define the territory affiliation. (Fogel-Chance 2006, 795). From winter to spring, the Inupiat traditionally lived in houses made of wood and sod, as several families continue to do. When the weather gets warmer, they move into tents, because the houses become uncomfortable and wet as the snow melts. [EH insert a comment and link to local concerns about climate change?]

Inupiaq social organization is based on kin ties, and families lived together or in separate dwelling linked by tunnels to enable easy visiting. As is explored elsewhere on this website, ceremonial life for these communities was closely tied to seasonal cycles of resource gathering and exchange with other communities, with the hunting leader, or Umalik, playing a leading role in ensuring both the material and spiritual well-being of the community.

According to the Alaska Native Language Center, the Inupiaq languages are closely related to the Canadian Inuit dialects and the Greenlandic dialects. It includes two major dialects groups: Seward Peninsula Inupiaq and North Alaskan Iñupiaq. This latter comprises the North Slope dialect found on the Arctic Coast from Barter Island to Kivalina, and the Malimiut dialect spoken around the Kobuk River and Kotzebue Sound. Seward Peninsula Inupiaq includes the Qawiaraq dialect, spoken in Teller and in the southern Seward Peninsula and Norton Sound area, as well as the Bering Strait dialect spoken in the communities surrounding Bering Strait and on the Diomede Islands. According to the Alaska Native Language Center, nowadays, the Inupiaq population is formed of 13,500 persons of whom about 3,000, mostly over 40 years old, speak the Iñupiaq language. Nowadays, most Inupiaq people speak also English.

(left: Photo Wales (Kingigan), Alaska (source: National Park Service); right: O.D. Goetze, hand-drawn map of the northwest coast of Alaska with Cape Prince of Wales at center made between 1896 and 1913 (source Alaska Museum of History and Art, AMRC-b01-41-261)

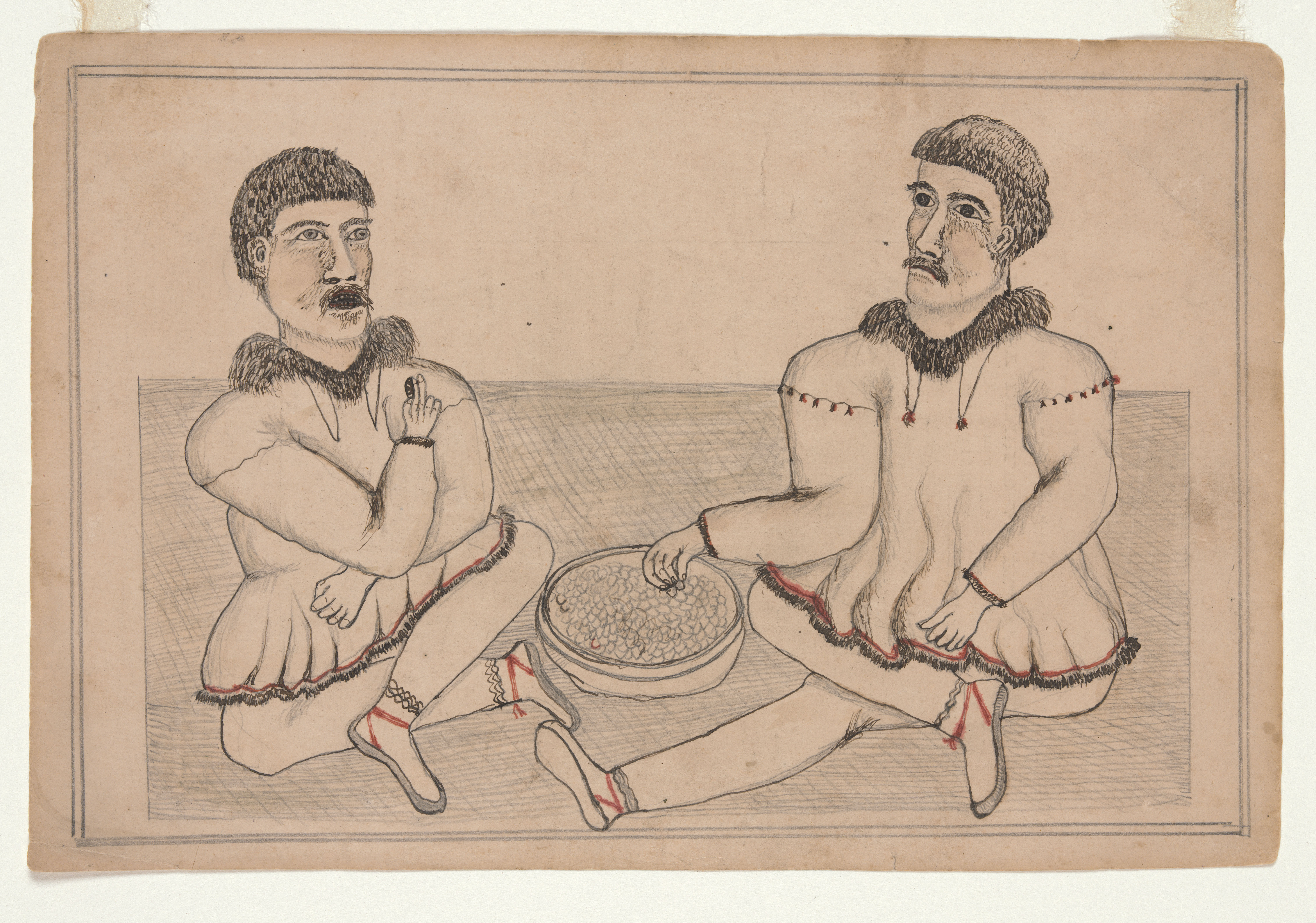

The drawings in this exhibition are believed to come from the village of Wales, or Kingigan, on the Seward Peninsula, which is the westernmost city on the continent of North America. Wales is part of the Bering Straits Native Assocation, established in 1967 in anticipation of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 and the Bering Straits Native Corporation, which was established in 1972 as the regional Alaska Native corporation. Wales was located along whale migration routes and became an important center for the whaling industry in the nineteenth century. At one point the village boasted more than 500 permanent residents; according to the 2010 census, Wales is currently home to 142 people.

The Immediate Historical Context–Cannelle Bruschini and Jaime Luria

During the first half of the 19th century, the Western influence was minimal on Inupiaq peoples of the Seward Peninsula. While Westerners were present in Alaska, they were uninterested in intervening in indigenous communities. According to Burch, “as of 1848, no European diseases are known to have reached the study region, no Westerners had tried to settle there, and no missionaries or other outsiders had attempted to transform Inupiaq beliefs or behavior.” (Burch 2006, 2) In 1848 this situation changed irremediably, because of two major events that occurred that year. In the first place, the first American whaling ship arrived in north Alaska. It initiated the increase of the whalers in this region over the next few years. They killed the walruses and the bowhead whales and by the early 1880s these two species had nearly been exterminated. This weakened the Inupiaq economy and impacted community life, as both animals were essential for physical and spiritual survival. In the second place, the first British Navy ship arrived also in Alaska in 1848, coming to the region as part of the massive search for the lost Franklin Expedition in search of the Northwest Passage. It was the first of many British ships. They visited the region in summer and initiated the contacts between the Westerners and the Iñupiat. In 1851, many Native people were killed by the first documented epidemic, at Point Hope, Icy Cape, Cape Smythe and Point Barrow. (Burch 2006, 2)

If the drawings were in fact produced around the suggested period, the Inupiaq communities to which the artists belonged were experiencing extreme social, economic, and political changes. The dramatic shifts that occurred as a result of accelerating political and economic disparities between Native Alaskan peoples and outside traders, politicians, and educators around the middle of-and certainly by the late-nineteenth century are central to understanding the kinds of materials produced in and dispersed from places like Cape Prince of Wales, Nome, and Saint Michaels. According to Dorothy Jean Ray, author and anthropologist of Native Alaskan cultures, it was the gold rush of 1899-1900 in the Nome area on Seward Peninsula, which, combined with the devastating measles epidemic of 1900, so affected Native peoples in ways that had never before been experienced. “At no other time in the historical period,” Ray writes, “could the ending of one era and the beginning of another be seen so clearly.” (Ray 1983, 9) The drawings in this exhibition are therefore situated within a context of trauma as well as struggles for cultural and political agency.

More on the history of Iñupiat – non-Iñupiat relations

More on Iñupiat Ceremonial Life

Sources for this page:

Alaska Native Language Center: http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/languages/i/

Ernest S. Burch, Social life in northwest Alaska : the structure of Iñupiaq Eskimo nations. Fairbanks :: University of Alaska Press, 2006

Dorothy Dean Ray, Ethnohistory in the Arctic: The Bering Strait Eskimo (Kingston: Limestone Press, 1983)

United States Census: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/cph-2-3.pdf)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.