ii. The ceremonial as an expression of Inupiaq values

–Sarah Diver

The relationship the Inupiat have with animals is predicated on the belief that all things have a spirit or soul, called inua, that returns to a spirit world to be reborn again after the containing body dies.[1] In order to be successful hunting, one must maintain proper social relations with the non-human persons (animals), endowed with the same inua as human life, by ensuring his or her spirit will return to be reborn.[2] Demonstrating respect for the inua of another being is achieved through group or individual reverential expressions in form of proper hunting and making techniques as well as ceremonials.[3]

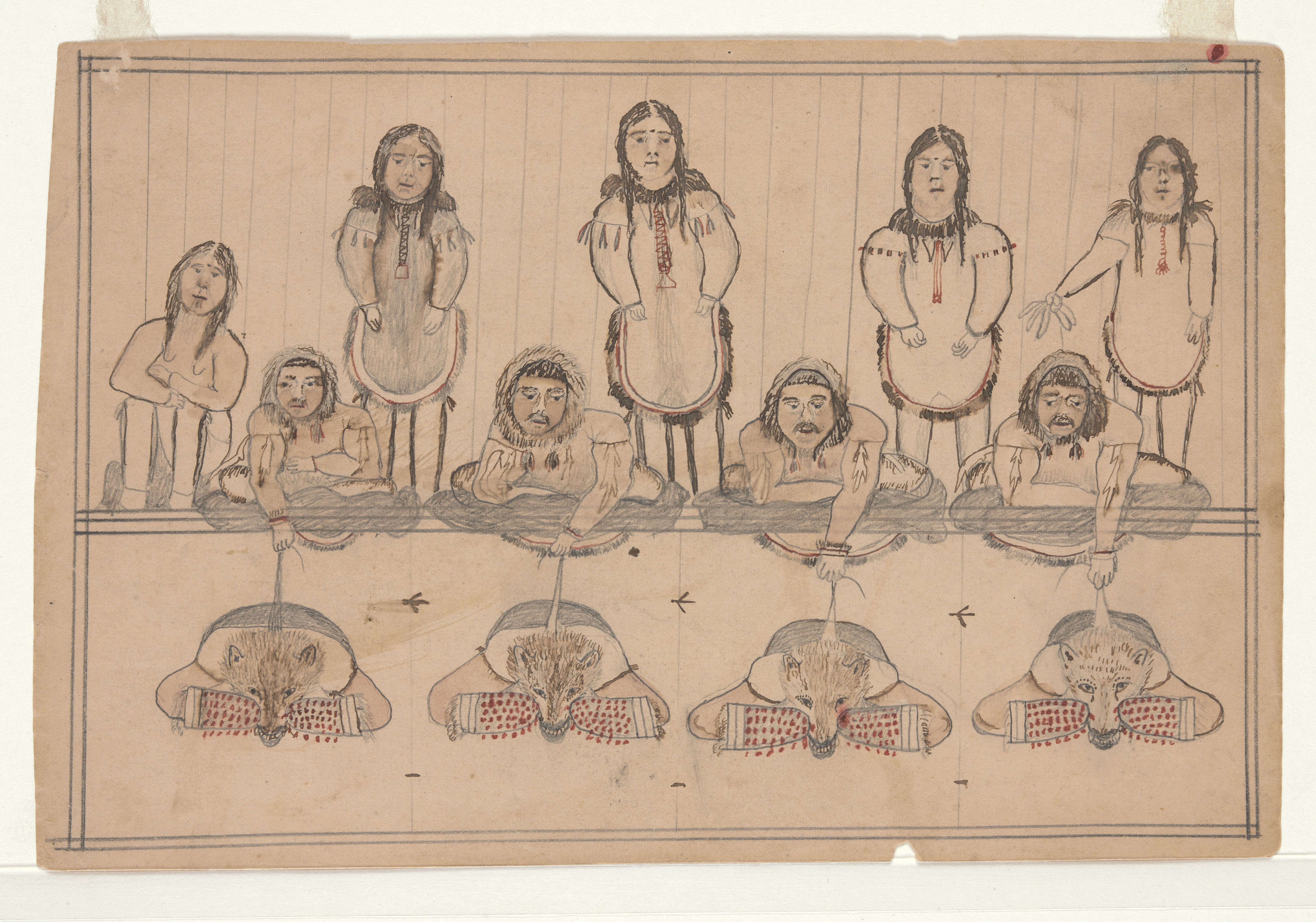

In addition to ensuring a favorable hunting season, ceremonials often served practical as well as social or spiritual function.[4] The drawings in question, for examples, depict scenes from a Messenger Feast, which allowed for the formation of alliances between unfriendly groups in addition to the exchange of goods unique to different geographic areas – especially the exchange of inland meats and furs for their coastal equivalents.[5]

Due to the advent of reindeer herding in the 1870s and 1880s, missionization, and the devastating effects of influenza in the early 20th century, the Messenger Feast was practiced with lesser frequency or transferred to different forms; however, some knowledge of its practice was not recuperated until its contemporary reemergence in 1988.[6] The 1890s, the period of time when the drawings were likely made, was a time of fluctuation and instability before disease and government-imposed changes in economic production completely disrupted the seasonal sustenance hunting patterns of the Inupiaq.[7] Subsequently, the Messenger Feast of the late 19th century was still practiced with great pomp and circumstance because previous ways of life remained only relatively unchanged compared to the turmoil that marked the decades that followed.[8]

The Messenger Feast occurs during the early spring or late winter and is the last of six seasonal ceremonies, which correspond with the seasonal shifts in hunting patterns.[9] Though there are many versions of the mythology behind the Messenger Feast, according to most accounts, the Eagle Mother saw the Inupiat were sad without the knowledge of singing and dancing, so she had her son kidnap a young hunter and teach him the essentials of performance, including how to build the box and round drums.[10] The Eagle Mother showed the hunter how to prepare the qargi to host his guests and execute the Kivgiq (Messenger Feast).[11] The hunter returned to the village where he taught everyone how to perform the Messenger Feast, and this made Eagle Mother happy and young.[12]

The Messenger Feast begins when two or more young men are sent from the village with asking sticks and specific songs or dances to perform when they arrive at a neighboring village.[13] The messengers receive requests for goods from those villages in exchange for their promise to participate in the event.[14] When the feasting time comes, the invited parties come prepared to exchange gifts, trade, feast, dance, sing, and participate in competitive sports.[15] This elaborate festival was part of coming-of-age rituals for young men and boys within the village to become initiated into the qargi, and it helped strengthen existing trading alliances aw well as providing welcomed sustenance and celebration at the end of winter.[16]

[1] King, J.C.H. “Introduction.” In Arctic Clothing of North America – Alaska, Canada, Greenland, edited by J.C.H. King, Birgit Pauksztat, and Robert Storrie, 13. Montreal and Kingston: Mc-Gill-Queen’s University Press, 2005.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Burch, Ernest S. “Role Differentiation.” Chap. 2 In Social Life in Northwest Alaska : The Structure of Iñupiaq Eskimo Nations, 71-72. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2006.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Fair, Susan W. “The Inupiaq Eskimo Messenger Feast: Celebration, Demise, and Possibility.” The Journal of American Folklore 113, no. 450 (2000): 464-94.

[6] Ibid, 482-484.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid, 468.

[10] Ikuta, Hiroko. “Inupiaq Pride: Kivgiq (Messenger Feast) on the Alaskan North Slope.” érudit 31, no. 1-2 (2007): 346.

[11] Ibid, 347.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Fair, Susan W. “The Inupiaq Eskimo Messenger Feast: Celebration, Demise, and Possibility.” The Journal of American Folklore 113, no. 450 (2000): 473.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ikuta, Hiroko. “Inupiaq Pride: Kivgiq (Messenger Feast) on the Alaskan North Slope.” érudit 31, no. 1-2 (2007): 347.

[16] Ibid.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.