b. George Ootenna

– Christopher Green

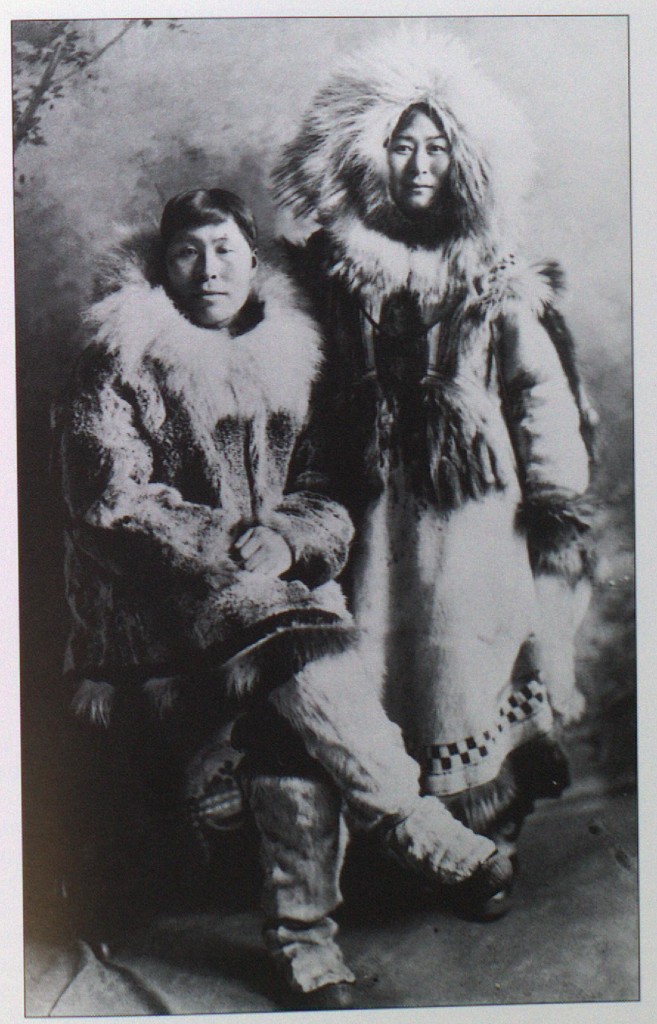

George Ootenna and his new wife, Nora, on their wedding day in 1900. Photograph courtesy of Kathleen Lopp Smith and Verbeck Smith. From Anungazuk 2003, 79.

Though many of the pencil and crayon drawings of Bering Strait Inupiaq life produced by Kingigan artist-students are anonymous, a number of artists are known to us by virtue of their having signed their works or by having their illustrations reproduced in the Eskimo Bulletin. One of those was George Ootenna, an apprentice herder at Kingigan, or Wales, whose negotiations of his Inupiaq way of seeing with Western perspectives exemplify the visual and cultural exchanges occurring on Cape Prince of Wales at the end of the nineteenth century. As histories and stories from community members atest, Ootenna was a man of great importance to the Kingigan community and contributed substantially to its survivance of tradition and culture. His drawings can be considered part of this legacy.

As part of the Sheldon Jackson’s government reindeer scheme, Tom Lopp selected a number of his male students to be his first apprentice reindeer-herders. Many of these apprentices were chosen from prominent Kingigan families and by 1895 there were nine young apprentice herders living with the Lopps at their school (Fair 2003, 51). George Ootenna was one of them, a descendent of Kingigan elders and a regular presence in the Lopps’ classroom.

Ootenna’s father was killed in the 1877 Gilley Affair, an incident which saw thirteen Kingikmiut killed by white men (Anungazuk 2003, 82), yet Ootenna, like the Kingigan community at large, harbored no ill-will towards the Lopps and other missionaries and outsiders. Instead he took part in Ellen’s lessons and became one of Tom’s most trusted apprentices. When Ellen’s brother, Charlie Kittredge, came to teach in Kingigan, Ootenna befriended the young man and taught him how to hunt (Fair 2003, 62).

Ootenna, along with his fellow reindeer herder-artists James Keok, Thomas Sokweena (Sokeinna), Stanley Kivyearzruk, joined Tom Lopp and the United States Revenue Cutter Service on the great Barrow Overland Relief Expedition of 1897, a rescue mission to the port at Barrow where a fleet of eight whaling vessels had become icebound. Along with other reindeer men and dog drivers including Ituk, Charley Artisarluk, Konuk, and Tautuk, Tom Lopp and his students drove a herd of reindeer several hundred miles to feed over two hundred sailors who were believed to be in danger of starvation. When the expedition arrived, however, it found that the sailors were in quite good shape, having been fed and cared for by the locals in the area (Andrews 1935, 90).

In 1900 Ootenna was married to Nowadluk (who went by the nickname Nora), another close friend of the Lopps who began working in their household as a helper in 1894 at the age of nine. A photograph of the two taken on their wedding day by Tom or Ellen Lopp is proof of how close Ootenna and his wife were to the Lopps and shows Ootenna as a young and spirited man. His energy was reflected by his success at the reindeer trade; he served as the primary assistant to Keok, whose herd reached nearly 800 animals by 1910, and Ootenna himself owned a modest herd of thirty-three animals by that time. He continued to travel the area managing and selling herds and deer well into the 1940s (Fair 2003, 54).

The 1918 influenza pandemic ravaged the Kingigan community, decimating its population and economy. Ootenna’s wife Nora perished along with most of Kiŋigin’s adult population. Few people of Ootenna’s generation survived the epidemic and he was one of a few men and women who took the reins of leadership during this troubled time. Ootenna is remembered for preparing the children of the community for responsible adulthood and as a valuable source of knowledge for the young. The role Ootenna played in his community’s cultural survivance cannot be understated. As Herbert Anungazuk noted in a written tribute, “Ootenna and other elders who were born before the influences from afar abruptly entered arctic circles lived in the ancient way of their ancestors…George Ootenna and the elders, past and present, held the banner of our heritage nobly. The surviving descendants must strive to go forward in like manner, and in the ways as taught to us by our fathers and grandfather” (Anungazuk 2003, 83).

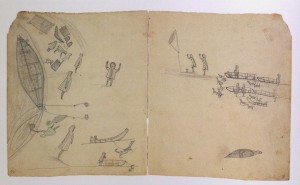

The drawings Ootenna produced at the turn of the century are visual forms of knowledge and heritage which continue his work even after his 1971 death. Drawn primarily in black pencil and ink on notebook paper, most of the works we know today were likely done in school with the Lopps. Many are signed and captioned, a way by which Ellen encouraged writing and the association of familiar subjects with English words. Thus many of Ootenna’s drawings depict scenes from his Inupiaq community of dance, games, hunting, and whaling. As scholar Susan Fair points out, he was the only one of the Wales group known to draw whaling scenes (Fair 2003, 67). As apprentice reindeer-herders, Ootenna probably did not participate in whaling crews, yet one drawing depicts a busy scene of a whale hunt come to shore [Fig. 1]. Ellen Lopp’s diaries reveal that drawing lessons were assigned at the school during whaling season in 1893, which might be the source of the subject matter. The drawing’s detail is a record of the flurry of activity following a successful umiak whale hunt. Multiple perspectives and scenes of action, from the butchering of the meat and excited jumping of sled dogs to the arrival of other men to assist with the distribution of the spoils, are joined together on the paper surface.

Fig. 1: Ootenna, Successful bowhead whale hunt at Wales, c. 1893-1900, pencil and paper, 19 cm x 32.6 cm. Kathleen Lopp Smith Collection, KLS 080a. From Fair 2003, 50.

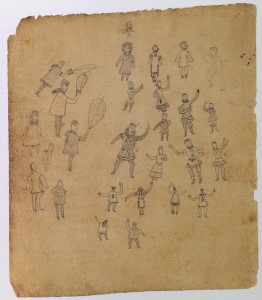

As Fair has claimed, of all the herder-artists Ootenna’s method most closely resembles the narrative style characteristic of earlier drill bow engraving and a broader Inupiaq graphic tradition. The subject matter of the whale hunt and the spatial treatment of the scene recall similar scenes on ivory. On paper, though, Ootenna’s humans are more fleshed out and display more motion than more linear engraved figures. This added visual information is fitting to the scenes of traditional drumming and dance which he drew [Fig. 2]. In one such drawing, drummers play for male and female dancers in what may be a Messenger Feast. Details of clothing like shoulder tassels and tails fastened to the rear of the parka are visible, and the motions of the dancers are easily legible. Like many ivory engravings, Ootenna’s subjects float all over the page, suggesting the view of multiple planes of existence and circular perspective characteristic of some Inupiaq peoples rather than a singular Western perspective (Fair 2003, 59, 65-67).

Fig. 2: Ootenna, Untitled. Inupiaq drummers and dancers, c. 1892, pencil on paper, 18.7 cm x 16.5 cm. Kathleen Lopp Smith Collections, KLS 079b. From Fair 2003, 59.

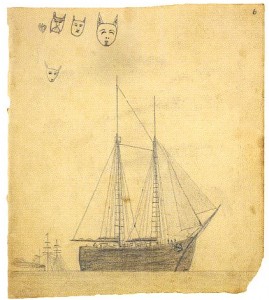

Ootenna’s drawings did not only focus on Bering Strait Inupiaq scenes, nor did they only engage his uniquely Inupiaq interpretations of space. A drawing of a sailing vessel in the deepwater port of Wales, a regular stop for trading, exploring, and whaling ships, depicts the kind of ship Kingikmiut men often hired on to in a singular perspective that is formally similar to the treatment of such ships on scrimshaw [Fig. 3]. The highly angular depiction of the ship by Ootenna reveals an understanding of linear perspective, reinforced by the more distant ship which slips beneath the horizon line. However, Ootenna has inserted a distinctly Inupiaq personal touch to the drawing; a number of disembodied heads, spirits or masklike faces, float in free space above the ship. As Fair notes, these faces may be symbolically associated with the visiting ships or simply Ootenna’s doodles (Fair 2003, 43). Notwithstanding they assert an Inupiaq presence into the scene of outsider arrival. Indeed those floating faces recall the freer multiplicities of spatial treatment in Ootenna’s drawings of the whale hunt and dancers. Next to the schooner’s linearity, it would seem that Ootenna could identify different Inupiaq and non-Inupiaq subjects with either indigenous or Western formal conventions, the latter having been introduced to the area by a variety of media.

Fig. 3: Ootenna, Untitled. Two sailing vessels with masks, c. 1893-1900, pencil on paper, 18.8 cm x 16.6 cm. Kathleen Lop Smith Collection, KLS 082a. From Fair 2003, 43.

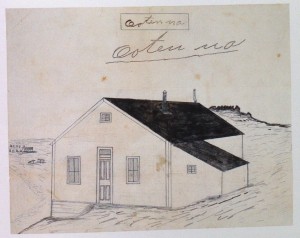

This combination of different formal conventions and perspectives within a single composition is best illustrated by a remarkable drawing of the Wales mission house [Fig. 4]. The drawing was an assignment due in Ellen Lopp’s class on May 18, 1893, during whaling season (Fair 2003, 61). The frame of the house is schematic, but rendered with attention to linear perspective in the diagonal lines of the roof and walls. Fair notes that the rocky hills and graveyard at upper right and umiaks on racks on the shoreline below include his Inupiaq perspective in the drawing. The two different approaches to space, depth, and perspective in this drawing are signs that Ootenna consciously chose which styles to use for this assignment, the depiction of the mission house. The house is a significant architecturally encoded space, its straight white walls and roof a foreign construction in the eyes of the Ootenna. It is appropriate, then, that to depict this very Western space Ootenna chose a Western form of perspective while using a treatment of space more familiar to the Kingigan community to depict the shoreline and ridge behind the house. Drawings like this one, in Fair’s opinion, contain “a tentative use of Western perspective” (Fair 2003, 47), but it seems clear that there is no tentativeness in these drawings; rather there was a pointed choice in which styles to use to depict these culturally encoded spaces. Photographs of the mission house may have provided Ootenna with the means or inspiration to produce a drawing with such contrasting approaches to space, or it may be that capturing the lines of the building was part of Ellen’s assignment. Regardless, Ootenna’s ability to contrast the hard angles and straight lines of the mission house with the non-linear perspective of the shoreline and local landscape identifies Wales and the Lopps’ school as a place of contact and exchange even as Ootenna maintains, formally and in his choice of subject matter, the Kingigan community’s Inupiaq traditions and world views.

Fig. 4: Ootenna, Untitled, Mission house at Wales, c. 1893, pencil and ink on paper, 19.6 x 25 cm. Kathleen Lopp Smith Collection, KLS 073. From Fair 2003, 61.

George Ootenna’s legacy lives on through his artwork and in the lives of those many people to whom he taught Inupiaq ways of life and seeing. A collection of anonymous pencil and crayon drawings by Ootenna can be found in the Peary Macmillan Arctic Museum at Bowdoin College (Ray 1996, 175, note 3). In 1985 the Ootenna Community Center at Cape Prince of Wales was named in his honour.

Sources for this entry:

Andrews, Clarence L. “Driving Reindeer in Alaska.” The Washington Historical Quarterly Vol. 26, No. 2 (April 1935): 90-93.

Anungazuk, Herbert O. “Ootenna.” In Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003: 77-83.

Fair, Susan W. “Early Western Education, Reindeer Herding, and Inupiaq Drawing in Northwest Alaska: Wales, the Saniq Coast, and Shismaref to Cape Espenberg.” In Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003: 35-75.

Ray, Dorothy Jean. A Legacy of Arctic Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

August 17, 2016 at 1:17 pm

You should have received reproductions and permissions directly from UAF (Lopp Smith collection) and other sources rather than crediting publications by Fair and others. There are minor errors, I am afraid that is how wrong information begins and becames standard. (Antisarlook and Kinegan and Kingikmiut are examples–though I understand the Lopps and many others made their own spellings of Inupiaq words).

Thanks for your coverage and review of this subject.