ii. The Expansion of the Inupiaq Graphic Art Tradition in the Late Nineteenth Century

Note: while it is important to acknowledge the the Inupiat are not a homogenous culture and that the tradition of ivory carving was by no means monolithic, it is meaningful to draw comparisons across their communities because of broadly shared cultural traditions and a long history of exchange within their territories. Work remains to be done identifying differences and specificities in the tradition amongst artists and communities, and how these different lineages of style may have intermingled through exchange. This essay will of necessity be limited to the graphic tradition produced by Inupiaq speaking peoples in the Bering Strait region, which I recognize could be misinterpreted as imposing a thoroughly Western and binary perspective on visual representation. Inupiaq visual literacy engaged objects such as models, dolls, and sculpture, and was by no means limited to a graphic tradition. There is no doubt in my mind that the drawings and engravings under discussion have been influenced by such other representational forms from Inupiaq culture(s). However the decision to limit this discussion to two-dimensional graphic form is an intentional framing to focus on a particular set of visual material, namely the drawings which emerged from the Wales mission school, and the potential visual influences which resulted in the innovative approach to representational form.

–Christopher Green

While scholars do not deny the long history of graphic art in the Bering Strait region, there are many questions remaining regarding the explosive expansion of pictorial practices in the 1890s that produced these drawings, in addition to a new class of ivory engravings which began to depict scenes resembling photographic reproductions and bird’s-eye views. When one compares the drawings and new engravings to the Inupiaq graphic art which preceded them, it is clear that there was a significant move from what scholar Dorothy Jean Ray has called the “old engraving style,” one using pictographic forms in composite perspectives, to the “western pictorial style,” which adopted more volumetric figures and conventions of one-point perspective and spatial depth. It is the goal of this paper to examine what at first seems to be a drastic stylistic shift by Inupiaq artists at the end of the nineteenth century and to firmly locate this shift in the history of the Inupiaq graphic tradition. Considered in typical Western conceptions of artistic development, there appears to be a gap between the “old engraving style” and the “western style” of the 1890s with little stylistic transition between the two (Ray 1977: 25, 43). However, rather than considering this shift as a development to a more mature and accomplished illusionistic depiction of the world along a particular teleological trajectory which reads increased artistic ability as resulting in increased naturalistic accuracy, I hope to investigate this shift as an expansion and innovation of Inupiaq graphic art practice. Rather than viewing this shift as part of a linear development from “bad” to “good” drawing which needs its holes filled in I want to frame this newfound mastery of Western forms of representation not as a loss-inducing change but as a choice made for the purposes of the Inupiaq artists. Inupiaq artists expanded their graphic practice to incorporate these Western styles while maintaining the heritage of earlier pictorial traditions, and in doing so complicate the binary that Ray suggests exists between an old, traditional style and a new, Euro-American one.

Framed as such, there remains an important question: where did these artists encounter a so-called Western pictorial style, and from where did they source the styles they adopted as their own? What visual materials were in circulation in the Bering Strait region to influence Inupiaq artists and to provide them with models for this expansion of visual practices? In the case of Inupiaq school drawings, it has come to be accepted that the influence of teachers and drawing lessons were the primary impetus of this artistic expansion. Susan Fair, for example, says that the influences of mission school teachers were the primary stimulant for local Inupiat to draw while the existing graphics tradition “simply made drawing on paper a natural adaptation when materials were provided by teachers.” (Fair 2003: 40) I hope that by considering the Inupiaq graphic tradition of the latter half of the nineteenth century I can link the innovations of the school drawings to similar innovations occurring simultaneously in the engraving tradition. I believe that by comparing the innovations of the school drawings to those of well known ivory engravers we can better understand the impetus and impact of these innovations and their visual sources beyond simply attributing it to the pedagogy of the teachers at Wales. It is of course integral to heed the different contexts in which school drawings and souvenir ivory engravings were produced, but in bringing the two together we might break down another dichotomy which Ray suggests exists between the souvenir trade and schools:

During the 1890s there were two parallel trends in Inupiaq art: one, the well established commercial souvenir world of Happy Jack, Guy Kakarook, and other purveyors of souvenir art, and another, the beginning of art instruction in American schools that were established in Inupiaq territory under church sponsorships. (Ray 2003: 19)

By placing Inupiaq school drawings, and Inupiaq drawings in general, in the same sphere of cultural production as souvenir and commercial goods rather than as parallel and without intersection, one can link the innovations of these art practices as emerging from the same traditions, visual sources, and as similarly expanding the range of pictorial devices at the artists’ disposal. As such, this page links to two discussions. The first outlines the formal history of the Inupiaq graphic tradition in the second-half of the nineteenth century as the forms of graphic art, embodied by ivory engraving and bow drills, changed to meet the demands of the growing commercial trade and shifting audiences and materials. The second section discusses two of the most well-known souvenir engravers and artists, Happy Jack and Guy Kakarook, and their respective styles. Here I will discuss both known and posited visual influences on these artists and how the appropriation of these sources led to their respective graphic innovations. The final section of this entry will then bring these sources of visual influence into the context of the production of Inupiaq drawings at the Wales mission school, considered to be the primary source of Inupiaq drawing in the Bering Strait region. The same sources which informed Happy Jack and Kakarook will be investigated as potential influences on the art of students at the Wales school, in addition to the unique circumstances of art lessons and access to particular materials given by teachers such as Ellen Kittredge Lopp. By determining the sources of the innovations of these Inupiaq draftsmen we can better approach the more pressing questions which arise when studying these drawings: why did these artists choose to expand the graphic style of their work, and to what end?

Bow Drills and the development of Inupiat Engraving

Graphic Art at the missionary school at Wales

We know that graphic art was being produced with an expanded repertoire of styles and techniques by artists who did not attend any of the government or mission schools in the area, but Fair maintains that “Undoubtedly, most early Inupiaq drawings and paintings from the area were produced at the Lopps’ home, made in conjunction with school lessons.” (Fair 2003: 40) Graphic art had existed in Bering Strait region for centuries, but rather than placing agency with the Inupiat to make the choice to draw, Fair overly emphasizes the outside influences which stimulated the local Inupiat to draw. The existing graphics tradition, for Fair, simply made drawing on paper a natural adaptation when materials were provided to the Inupiat by teachers. When Ellen and Tom Lopp arrived in Wales as teachers, they brought drawing paper, pencils, watercolors, and a printing press, “and a love of art” which Fair suggests led to the development of Inupiaq drawing (Fair 2003: 44). In contrast, I would like to put the emphasis on the students by placing them in the same agency-granting space as artists like Happy Jack and Kakarook. Just as those two artists chose to use available visual sources such as photographs, scrimshaw, printed illustrations, and other Western pictorial devices to expand the Inupiaq graphic tradition , the students of the Wales mission school chose to use the alternative artistic styles being presented to them to their advantage. This final section, then, looks to the visual sources available to Happy Jack and Kakarook as also being potential sources for the Inupiaq draftsmen because they were artists working from the same tradition at the same moment. Breaking down the division between commercial engravers and academic drawers allows us to see how those school-attending reindeer-herding artists could find visual source material to expand their artistic practice in the same places Happy Jack and Kakarook were finding it. Finding these sources outside the structure of the school system presents the possibility, following Lisa Wexler’s example, to see these drawings as sites of agency and resistance rather than as assimilation projects through drawing lessons and style (Wexler 2006: 17 – 34).

There is no doubt that the art lessons of the Lopps, and Ellen in particular, were a primary source of influence at Wales. The availability of materials alone allowed for the same kind of innovation in style that we saw in Kakarooks notebook drawings: the larger scale of paper and greater vertical support compared to ivory allowed for an increase in the size and detail of figuration by those who might not be masters with the engraving needle or bow. That is not to say that materials were abundant; the use of the blank reverse of printed illustrations for drawings by the students shows how valuable every sheet of paper was.[1] Ellen Lopp herself was a competent draftswoman who often included her own sketches in letter home to her family. During the Lopps’ extensive travels in the Bering Strait region, Ellen likely sketched and thus demonstrated drawing to a dispersed group of locals. In the classroom she realized that traditional Inupiat learn by observation, not by directive methods, and respected this in her pedagogy. As a result, materials for drawing and painting, stimulating readings and catalogues, and musical instruments were always available, and no doubt many of the students were influenced by Ellen’s demonstrations of her own drawing abilities (Fair 2003: 39). Ellen capitalized on the innate Inupiaq artistic abilities, and while her students were timid about speaking she found success by incorporating crafts and writing into her lessons. “We have counting, drawing, ABCs, and kindergarten work.” (Smith and Smith 2001: 273)

The letters of Ellen describe their enthusiasm for having locals in to their home where one of the primary entertainments was looking at pictures. These pictures were likely the kinds of printed images from children’s weeklies, magazines, and books which teachers like Ellen must have brought north with them, as well as personal illustrated books and Bible pictures.[2] Visitors to the hospitable Lopps who engaged in their own art making were no doubt inspired by the many drawings and illustrated materials they saw in the Lopp home. And such sustained looking at images for entertainment must have encouraged the Wales students in the drawing assignments which became a regular part of the school curriculum, including lessons on copying illustrations and writing.

Printed illustrations would not have been the only visual source material in Wales. Photographs were in abundance. Tom Lopp took photographs of village life and eagerly attended ceremonies in village qargit to document them (Fair 2003: 38). There is substantial evidence of the presence of photographs at Wales in Ellen’s letters. Miner W. Bruce, for example, who came to Alaska on the same ship as Ellen, had a camera and according to Ellen in June 1892 “has taken a number of pictures. He says he will give me one to send you.”[3] In other letters, Ellen suggests the frequency with which photographs were taken of the landscape, teachers, and the Inupiat.[4] Ellen also writes of sending her family pictures and included at least on in a letter to Charlie, her younger brother, in 1892.[5] Photographs, then, were certainly present as a visual source. Given the extensive use of photography by the contemporary figures Happy Jack and Kakarook, it is equally possible that the Inupiaq artists in Wales could have similarly used photographs as visual inspiration and aid. It is even possible that the Lopps used copying from photographs as a teaching tool – in a June 16, 1893 letter to her sister Alice, Ellen writes about the creation of the Eskimo Bulletin, noting that “Mr. Lopp printed it and drew the pictures from photographs.” The Lopps, then, were familiar with the technique of copying from photographs and well may have incorporated it into their lessons.

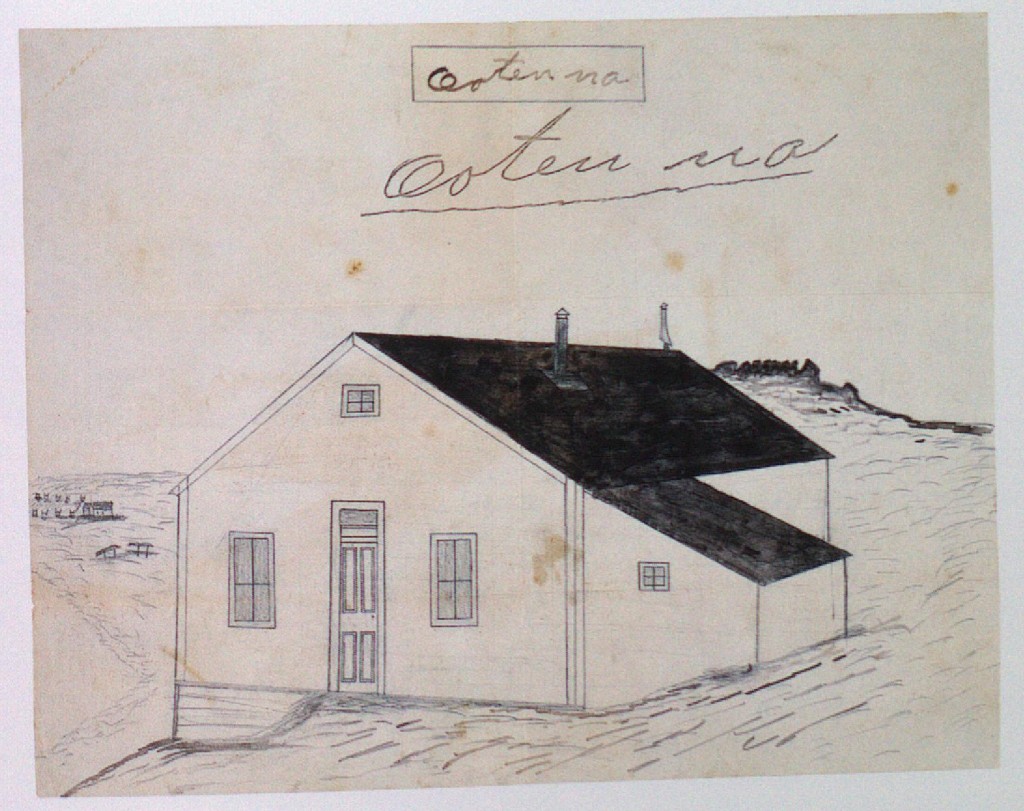

One drawing from 1893 might be evidence of the use of photography as a model for an graphic style that in the school drawings has expanded to include forms of pictorial depth and persepctive which are more common to Western practice [Fig. 1]. It is a drawing of the mission house at Wales by a student who has signed his name, Ootenna. The drawing was an assignment due in Ellen Lopp’s class on May 18, 1893, during whaling season.[6] The frame of the house is schematic, but rendered with attention to linear perspective in the diagonal lines of the roof and walls. Fair notes that the rocky hills and graveyeard at upper right and umiaks on racks on the shoreline below put the drawing back in what she calls “proper Inupiaq perspective,” meaning a non-linear or combined perspective which is both frontal and aerial, much like the treatment of space on drill bows from half a century prior. The two different approaches to space, depth, and perspective in this drawing are signs that Ootenna is consciously choosing which styles to use for this assignment, the depiction of the mission house. The house is a significant architecturally encoded space, its straight white walls and roof being a foreign construction in the eyes of the Inupiaq. It is thus appropriate that to depict this very Western space, Ootenna chose a Western form of perspective while using a more traditionally Inupiaq treatment of space to depict the shoreline and ridge behind the house. Drawings like this one, in Fair’s opinion, contain “a tentative use of Western perspective,” (Fair 2003: 47) but it seems clear that there is no tentativeness in these drawings; rather there was a pointed choice in which styles to use to depict these culturally encoded spaces.[7] And when we compare this drawing to a photograph of the mission house from a similar angle, the similarity is striking [Fig. 2]. The photograph similarly contrasts the hard angles and straight lines of the mission house with the shoreline and landscape seen from a high angle that approaches aerial. Such a photograph may have provided Ootenna with the means or inspiration of producing a drawing with such contrasting approaches to space.

Fig. 1: Ootenna, Untitled, Mission house at Wales, c. 1893, pencil and ink on paper, 19.6 x 25 cm. Kathleen Lopp Smith Collection, KLS 073. From Fair 2003, 61.

Fig. 2:John M. Justice. First Wales Mission House, 1895. Lopp Family Photograph Collection, Alaska and Polar Regions Department, University of Alaska Fairbanks. From Smith and Smith 2001: 44.

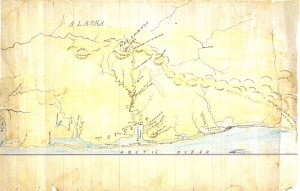

While there are no school drawings akin to Kakarook’s bird’s-eye views, another form of spatial organization was taken up by Wales students in their drawing: the map [Fig. 3]. The map illustrated, for example, was drawn by one of Tom and Ellen Lopp’s herder-students, several of whom were skillful writers. The astute sense of place and attention to detail exhibited by Inupiaq hunters resulted in the ability to readily draw maps of regions they frequented. While Benedict Anderson has shown us that the map is a primary tool of colonialism, this drawing shows signs of the assertion of indigenous conceptions of place. Place-names on this map have been spelled phonetically by the artist. Rather than being uniform, as in a Euro-American map, the place-names on this drawing are inconsistent in size. The larger words seem to denote places of greater importance: Hot Springs, for example, one of the largest names on the map, was a site for shamanistic initiation, healing, and recreation (Fair 2003: 42). And just as Kakarook’s bird’s-eye views were created on both paper and ivory engraving, so too was the form of the map [Fig. 4]. Like the drawing, the map was asubject popular with early-day Nome ivory artists. This particular tusk has been employed to depict the elongated map of the coastline stretching beyond Unalakleet to Cape of Princeton Wales (Ray 1996: 115). This engraved map is similarly labelled with phonetically spelled place-names and is further proof that similar forms and themes were being deployed by both the commercial ivory engravers and the students at Wales.

Fig. 3: Sokeinna or Keok, Untitled, Map of Saniq-Saniniq or “Tapqaq” coast, c. 1893-1900, ink and colored pencil on paper, 20.3 cm x 31.5 cm. Kathleen Lopp Smith Collection. From Fair 2003: 39.

Fig. 4: Anonymous, probably Nome or King Island. Walrus ivory tusk with engraved map. About 1915. 20 1/4”. From Ray 1996: 114.

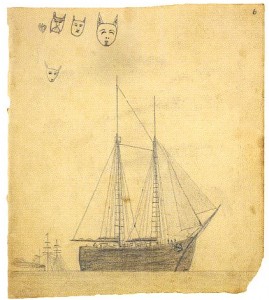

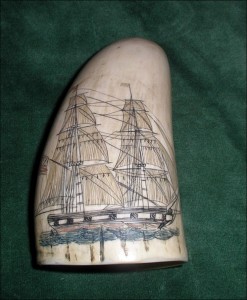

The influence of scrimshaw on Inupiaq drawings is less clear than in the case of engravers like Happy Jack, but as scrimshaw was in circulation in the whaler-heavy area of Wales for decades it remains a possible visual source for the expansion of the graphic tradition in the area. Another drawing by Ootenna reveals possible formal connections to scrimshaw when compared to the forms of scrimshaw ships [Figs. 5, 6]. Wales has a deepwater port and lies at a strategic location for trading, exploring, and whaling. Inupiaq men from this region often hired on aboard such ships, traveling widely and often serving as translators (Fair 2003: 47). The experiences Happy Jack had on several whaling ship trips that provided the exposure to scrimshaw sources and results in some of his artistic innovations, then, would have similarly been available to residents of Wales who could have hired aboard the kind of ship Ootenna depicts here. Fair notes that the spirits or masklike faces which float above the depicted schooners might be symbolically associated with the visiting ships or just Ootenna’s doodles, but they insert the personal touch of Ootenna’s Inupiaq hand into this highly linear depiction of a ship.

Fig. 5: Ootenna, Untitled. Two sailing vessels with masks, c. 1893-1900, pencil on paper, 18.8 cm x 16.6 cm. Kathleen Lop Smith Collection, KLS 082a. From Fair 2003, 43.

Fig. 6: Polychrome scrimshaw tooth with unnamed brig. Sperm whale tooth, 19th century. Peter C. Barnard Collection, Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Bowdoin College.

In her book The Tlingit Encounter with Photography, Sharon Bohn Gmelch tell us that after their earliest encounters with photography, the Tlingit were able to exercise some degree of control over their representation by this foreign visual tool and found their own uses for the photographic medium. Gmelch makes an argument for the Tlingit as being more than colonized or victimized by Euro-American photography.

Chiefs and other persons of high rank…used photography intentionally to assert their status or to demonstrate their connections to American culture. Photography was also used by the Tlingit to validate their ownership of clan crests and valuable regalia, to immortalize important events and people, to remember the dead, to create personal keepsakes, and sometimes to make money. (Gmelch 2008: 186)

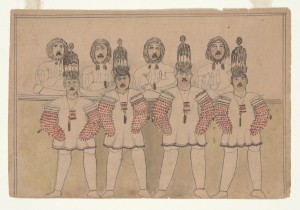

In the Inupiat’s nineteenth century encounter with a variety of foreign visual forms, from photography to printed illustrations to scrimshaw, artists were able to exercise control over these forms by appropriating them and integrating them into the long pre-existing history of graphic art in the Bering Strait region. Inupiaq engravers and drawers did not discover, develop, or grow into a Western pictorial style. Rather they encountered it and took hold of it for their own ends. While they might not have had access to the camera taking the photographs, they could adopt those representational forms and techniques to represent themselves in visual terms understood by their teachers, clientele, and kin. Co-opting the means of representation of the Other was an assertion of status and ability while demonstrating a connection to, understanding of, and making one’s own of white culture. Rather than an assimilation, the depictions of portraiture, hunting, dancing, and ritual which fill the drawings and engravings alike at the end of the nineteenth century can be read as assertions of presence. In a drawing of dancers [Fig. 7], then, we can see an assertion of self that takes a photograph [Fig. 8] and turns that visual format, that representation of a people, into a depiction of self. In the adaptation of foreign representational devices, Inupiaq artists were able to expand and innovate the tradition of their graphic arts to represent themselves in a way that was responsive to the changing circumstances of their world.

Fig. 7: Drawing likely by Inupiat apprentice caribou herder, Wales, early 1890s. Columbia University Art Properties

Fig. 8: Dancers in Qazgi at Wales, 1892. Lopp Family Photograph Collection, Alaska and Polar Regions Department, University of Alaska Fairbanks. From Smith and Smith 2001: 104.

Sources used for this entry:

Bernardi, Suzanne R. “Whaling with Eskimos of Cape Prince of Wales.” The Courier Journal (October 20th, 1912): 1-12.

Bodenhorn, Barbara. “‘People Who Are Like Our Books’: Reading and Teaching on the North Slope of Alaska.” Arctic Anthropology 34, No. 1 (1997): 117 – 134.

Burch, Ernest S. Jr. The Inupiaq Eskimo Nations of Northwest Alaska. Fairbanks, 1998.

Fair, Susan W. “Early Western Education, Reindeer Herding, and Inupiaq Drawing in Northwest Alaska: Wales, the Saniq Coast, and Shismaref to Cape Espenberg.” In Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003: 35-75.

—– Alaska Native Art: Tradition, Innovation, Continuity. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2006.

Fogel-Chance, Nancy. “Fixing History: A Contemporary Examination of an Arctic Journal from the 1850s.” Ethnohistory 49, No. 4 (October 2002): 789‑820.

Gmelch, Sharon Bohn. The Tlingit Encounter with Photography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Graburn, Nelson H. H. and Molly Lee. Commerce and Curios: The Alaska Commercial Company, 1868-1904. Berkeley: Lowie Museum of Anthropology, 1986.

Graburn, Nelson H. H., Molly Lee, and Jean-Loup Rousselot. Catalogue Raisonné of the Alaska Commercial Company Collection. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Himmelheber, Hans. Eskimo Artists. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1993.

Hoffman, Walter James. The Graphic Art of the Eskimos, United States National Museum Annual Report for 1895. Washington, DC: GPO, 1897.

Jones, Suzi. Eskimo Drawings. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003.

Malloy, Mary. Souvenirs of the Fur Trade: Northwest Coast Indian Art and Artifacts Collected by American Mariners 1788-1844. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Mollett, David. “Rendering the Arctic: Artistic Considerations in the Eskimo Graphic Arts.” In Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003.

Phebus, George, Jr. Alaskan Eskimo Life in the 1890s As Sketched by Native Artists. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1995.

Rathburn, R.R. “The Russian Orthodox Church as a Native Institution among the Koniag Eskimo of Kodiak Island.” Arctic Anthropology, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1981): 12-21.

Ray, Dorothy Jean. “Alaskan Eskimo Arts and Crafts.” The Beaver (Autumn 1967): 80-91.

—– Eskimo Art: Tradition and Innovation in North Alaska. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977.

—– Artists of the Tundra & the Sea. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1980.

—–“The History of Alaskan Eskimo Art in Ivory.” In Dinah Larsen and Terry Dickey, eds., Setting it Free: An Exhibition of Modern Alaskan Eskimo Ivory Carving. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Museum, 1982: 9-36.

—– A Legacy of Arctic Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

—–“Happy Jack and Guy Kakarook: Their Art and their Heritage,” in Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings (Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003: 16-33.

Smith, Kathleen Lopp and Verbeck Smith, eds. Ice Window: Letters from a Bering Strait Village 1892-1902. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2001.

Thornton, Harrison R. Among the Eskimos of Wales, Alaska 1890-93. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1931.

VanStone, James W. “The Bruce Collection of Eskimo Material Culture from Port Clarence, Alaska.” Fieldiana Anthropology 67. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1976: 1-117.

Wexler, Lisa M. “Learning Resistance: Inupiat and the US Bureau of Education, 1885 – 1906 – Deconstructing Assimilation Strategies and Implications for Today.” Journal of American Indian Education 45, No. 1 (2006): 17 – 34.

Endnotes

[1] Indeed in a letter dated October 2, 1892, Ellen Lopp described the valuables in a wedding present, primarily pedagogical and art materials: “The package from Dr. Jackson, a wedding present, was quite a collection: some pens and lead pencils, an indelible pencil, rubber bands, an ink eraser, a bottle of cologne, a patent escritoire to carry in the pocket, and some other small things.” Smith and Smith 2001: 42.

[2] Ellen Kittredge Lopp, Letter to Mamma, dated October 10, 1892, “[Kongik, a little girl] is sitting on the floor in front of me now looking at pictures.” Regarding Bible pictures, in a January 8, 1893 letter to her mother, Ellen says “We will take charts of Bible pictures” on the school’s hectograph, a duplicating machine, proof that the Lopps were showing an illustrated Bible to their students and visitors. Smith and Smith 2001: 45, 50.

[3] Ellen Kittredge Lopp, Letter to her mother, dated June 14, 1892. Smith and Smith 2001: 22.

[4] Ellen Kittredge Lopp, Letter to Susie Kittredge, dated June 3, 1892, Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska: “[Mr. Bruce] had come over in an earlier boat to take some views [photographs].” Smith and Smith 2001: 30.

[5] Ellen Kittredge Lopp, Letter to Charlie, August 27, 1892, Port Clarence. Smith and Smith 2001: 39.

[6] A journal entry by Ellen on 18 May 1893 states “61 at school. Drawings of house brought in. Some very good. Knitting class making many of the girls lose interest in school. Erokhana spent the afternoon and sat with Mr. Lopp while he wrote Mr. [Miner] Bruce’s letter…Kongik bad cold.” In Fair, 2003: 61.

[7] In addition to two-dimensional works, other forms of Inupiaq art demonstrate a highly adept conception of spatial arrangements. Models of interiors, for example, are signs of Inupiaq artists conceiving of and representing ceremonial spaces spatially in three-dimensional form. For example see Alaska State Museum’s ivory model depicting the Eagle-Wolf dance in a qavgit interior, reproduced in Ray, 1977: 165, fig. 144.

July 16, 2016 at 5:51 pm

Very important work. Quyana. Images of western items – ships, schools, teacher housing, tools very western drawing. Traditional life shown in a more traditional way but translated in style if given to an outsider. This might be a way to consider some of this.