g. Bow Drills

Man using a bow drill. King Island, circa 1920.

Photo by Edward S. Curtis, courtesy of the Library of Congress, 3a16199

Note: while it is important to acknowledge the the Inupiat are not a homogenous culture and that the tradition of ivory carving was by no means monolithic, it is meaningful to draw comparisons across their communities because of broadly shared cultural traditions and a long history of exchange within their territories. Work remains to be done identifying differences and specificities in the tradition amongst artists and communities, and how these different lineages of style may have intermingled through exchange.

–Christopher Green

The graphic arts of the Bering Strait region have their origins in prehistory. Pictographs and petroglyphs are relatively uncommon in Nothern Alaska, but the few that exist tend to illustrate human figures in simple linear forms (Ray 1967, 84). To the south the Yupik extensively used graphic motifs and pictorial narratives to recount ancestor-stories through painting on drums and wooden bowls (Himmelheber 1993, 16-31), but the Inupiat most widely found two-dimensional aesthetic expression through the engraving of representational subjects in ivory. Likely influenced by Northern Asian cultures, these engravings were done primarily on walrus ivory but also on other types of bone. Many types of objects were produced and decorated, including tools, combs, and bag handles, but the height of engraving art was produced on the drill bow handle, an essential tool of the ivory carver.[1] Dorothy Jean Ray is the foremost scholar on this engraving tradition, first recorded with a drill bow from Captain Cook’s 1778 expedition, and she has meticulously explored its history (Ray 1982, 9-36). As Ray has shown, the drill bow’s graphic form evolved from simple linear and geometric motifs to busy, historically and socially informative pictographic scenes.

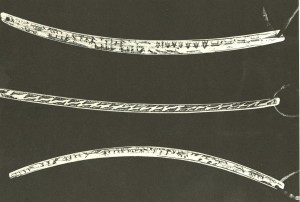

In Ray’s view, early pictographs on ivory drill bows fall into two types. The first depicts construction of boats and the trophies of animals killed or trapped. Tallies of animals shown by multiple animal skins or bodies depicted in a row. Ray calls these “journal” bows, and notes that as many appear to have been left uncompleted they have the quality of a journal or work in progress, marking individual accomplishment [Fig. 1]. The second type portrays a variety of scenes from Inupiaq life, including men hunting, whaling, mythological animals, wrestling, villages, ceremonies, and an abundance of caribou both living and dead (Ray, 1982, 259-261). By the mid-nineteenth century, following decades of sustained European contact, whaling ships and non-Native weapons were often illustrated, even the building of the Western Union Telegraph Expedition at Port Clarence in 1866-67 (Ray 2003, 19). For example, a drill bow from the collection of the British Museum, dated 1848-54, is believed to depict the activities of men searching for the Franklin expedition at Bering Strait [Fig. 2]. While the forms of all the figures are done in the same pictographic style, the European scenes (identifiable by the rifles and blacksmithing) are coloured black while the Inupiaq scenes are red, graphically differentiating Inupiat from foreigner (Ray 1977, 220).

Fig. 1: Three sides of a ivory drill bow, 1880s. 17 1/4” long. Lowie Museum 2-4121. Collected by Rudolph Neumann of the Alaska Commercial Company, probably in the St. Michael area. From Ray 1977, 215.

Fig. 2: Drill bow from Port Clarence depicting activities of men searching for the Franklin expedition at Bering Strait, 1848-54. British Museum #Am1855,1126.227.

The origins of drill bow art are unclear, but several explanations have been proposed. The Inupiat may have borrowed idea from early explorers prior to Cook’s voyage, considering that Europeans had been at the Bering Strait as early as 1650, but it is difficult to substantiate any kind of contact which may have resulted in the exchange of ivory engraving techniques. More likely is that Thule ancestors, who had invented the bone drill, independently came up with the idea. This is supported by the variety of small objects with simple images of people, birds, and animals that have been excavated from Thule archaeological sites, including at Cape Prince of Wales (Ray 2003, 19). Regardless, in the drill bow we can see that in historic times pictographic art was widespread among the Inupiat and throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries they were recording scenes and event from the world around them. These engravings provide us with glimpses of life from the Inupiaq point of view, indigenous activities as well as the changes and interactions produced by European contact.

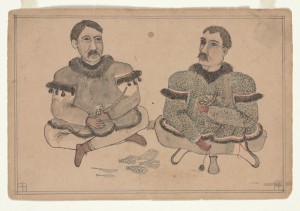

Inupiaq pipe, carved ivory inscribed with ink, 1880-1900. Collection history unknown; purchased by MAI from the Fred Harvey Company (Indian arts dealers in the Southwest) in 1917 using funds donated by MAI trustee James B. Ford (1844-1928). NMAI 6/2445 (http://www.nmai.si.edu/searchcollections/item.aspx?irn=67008&partyid=2576&src=1-2)

However, in the late 1800s the engraved drill bow was replaced by other forms of engraved ivory. By the 1890s, Miner W. Bruce, a reindeer man turned trader and collector who was brought to Port Clarence to establish Alaska’s first reindeer station under the direction of Sheldon Jackson, reported only being able to obtain six engraved works from Port Clarence, five of them souvenir pipes, out of 425 total objects (VanStone 1976, 117). Artists transferred their talents to the making of souvenir objects like ivory pipes, and though these Inupiaq scenes continue to show a record of activities and scenes of daily life they were no longer made for the artist’s own remembrance or for possible communication with his peers but instead products for the souvenir trade (Ray 1996, 105). The demise of drill bow art and the development of new ivory forms such as souvenir pipes coincided with the establishment of American trading companies on the mainland of northwest Alaska following the Alaska Purchase in 1867.The Alaska Commercial Company (ACC), as one primary example, played a prominent role in the Alaskan curio trade and encouraged the creation of souvenir ivories by providing a significant market for the engravings of Alaskan natives. Curios had been traded in the area for centuries, particularly with Russian traders, but the ACC strengthened the already existing market by reselling curios at its Kodiak and Unalaska posts to vessels bound for and from the high Arctic who stopped for supplies. In addition, the company sold curios on consignment to burgeoning tourist centers along the Inside Passage of southeast Alaska, and sent them south for resale in Seattle and San Francisco. The Smithsonian even turned to the ACC for help gathering objects for the museum’s collection, and the ACC requested its agents to obtain documentation for the artifacts they collected, including Native use and terminology, as part of the ethnographic impulse (Graburn 1996, 35).[2]

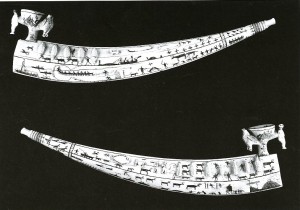

The rise of objects like the engraved pipe, then, coincided with the demise of the pictorial drill bowl and a burgeoning commercial souvenir trade. The beginnings of “market art” represents the response of ivory carvers to the requests of commercial whalers, then prospectors, missionary teachers, and collectors in the late 1800s. The well-established art of graphic engraving was put into the service of commerce and “made for traders” as Walter James Hoffman put in a 1895 report to the United States National Museum on the state of Eskimo art (Ray 2003, 194). Places like St. Michael and Nome, once the gold rush hit, became hubs for ivory carving, and outsiders brought in trade goods and introduced a cash economy (Fair 2006, 35). Inupiaq ivory pipes, copied after wooden models used in northern Alaska, were made to order for traders [Fig. 3]. The engraved images on the pipe were typically larger versions of the pictographic forms found on drill bows, so it is likely that the engravers had also been drill bow artists. Like the drill bows, all sides of the pipes are covered with scenes of Inupiaq daily life. Missing, though, are the non-Native images such as whaling ships or Euro-Americans with guns which were to be found on mid-century drill bows. These pipes, then, were obviously meant to be wholly “Eskimo” products, “genuine souvenirs of genuine Eskimo life” which did away with depictions of Westerners to feature the native themes that traders expected and wanted to see in their curios (Ray 2003, 21).

Fig. 3: Two sides of a fancy ivory pipe with both small sculpture and engraving, Seward Penninsula, 1880s. 39.4 cm long. Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology. From Ray 2003, 21.

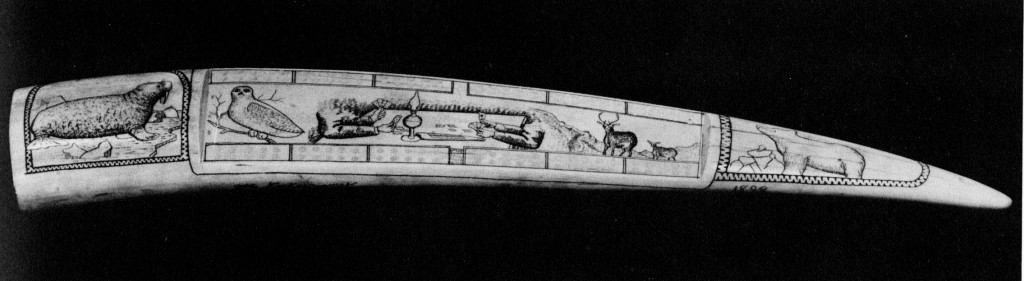

As Ray tells us, production of these pipes seems to have been limited to 1870s and 1880s, because by the 1890s two new souvenir products overtook their popularity: whole polished tusks and cribbage board, both with a variety of engraving styles. Walrus tusk art began sometime in 1870s when the Alaska Commercial Company post at St. Michael began trading for walrus tusks and either gave away or sold the tusks to men for engraving. St. Michael quickly became the center for souvenir pipes and tusks when northern Inupiat immigrated there for trade and work. At first the style of these tusk engravings followed that of the drill bows and pipes. The pictographic figures are maintained, but the scenes are expanded substantially in scale to fill the larger ivory expanse of the whole tusk surface. But soon what scholars have referred to as a “Western style” began to appear on whole tusks and cribbage boards [Figs. 4, 5]. This engraving style depended upon intricate details for what might be considered more “realistic” representation: facial features and details of animal fur, bird feathers, sleds, boats, and buildings were usually carefully depicted. Ray suggests that the development was in part the inevitable result of travellers looking for souvenirs. Traders and gold-rush customers quickly learned that the Alaskan natives had a talent for copying illustrations and objects in either two or three dimensions and were eager to have products that combined the curio pipe’s ivory “Eskimo-ness” and the commemorative picture of the souvenir postcard or engraving.[3]

Fig. 4: Anonymous, Nome. Walrus ivory cribbage board: reverse sides and detail. 28 1/2”. Top side engraved with an Eskimo village and a contingent of soldiers; reverse engraved with a panorama from Nome to Cape Nome. 1909. From Ray 1996, 112.

George Phebus Jr. demonstrates the Western-centric pitfall of approaching this fundamentally different style of Inupiaq engraving that emerged in commercial ivory goods at the end of the nineteenth century as a development to higher degrees of artistry:

“More fundamental change stimulated by Yankee whalers’ scrimshaw and other contemporary illustrations occurred when Eskimo carvers began to decorate cribbage boards and entire walrus tusks with hunting scenes, landscapes, ice floes, and fully rounded figures. Delicate shading indicated land forms, sea ice, and texture of fur and clothing…These later engravings, showing true perspective, were the ivory equivalents of sketches and watercolors.” (Phebus 1995, 7)

Phebus suggests that this shift to fully rounded figures and “true perspective,” meaning here of course a Western style of perspective, is more nuanced, more delicate, and more akin to the sketches and watercolours of true artists. He seems to suggest that through the influence of the shading and fully rounded figures of whalers’ scrimshaw and contemporary illustrations the Inupiat are finally capable of producing hunting scenes and landscapes, subjects which of course had been produced in a pictographic style for the better part of a century. Phebus cannot see past what he considers the “true” perspective of a Western style of graphic art to see that the souvenir ivory engraving trade continued to portray a variety of subjects from a native perspective. Susan Fair falls into a similar trap, noting that the Inupiat “began engraving more realistic scenes on whole ivory tusks or fashioning cribbage boards to suit a Western market, then began carving single ivory figurines and scenes” (Fair 2003, 46), and as we have already seen Ray calls them entries into Western pictorial perspective. It is of utmost importance to recognize that the Inupiaq artists and engravers of this moment are not leaving their own tradition to “enter” into a Western one – the use of pictorial illusionism does not necessitate being more “real”, just as the adoption of a different treatment of space and illusionism does not represent a more “true” perspective. Rather we should allow that the Inupiaq artists enfolded these Western aesthetic approaches into their own graphic tradition, and in doing so adopted a new pictorial style to operate in the commercial context many of these works were created in. By offering a product with a style as recognizable and familiar to the Euro-American collector audience as it was to Phebus, Inupiaq engravers could sell to a market which clearly no longer desired the type of old engraving style which made earlier curios attractively “Eskimo-looking.”

Fig. 5: Joe Austin, ivory cribbage board signed “Joe Kakavgook,” 1898.18 1/2” (47.5 cm). American Museum of Natural History 60.1/5989. From Ray 1977, 233.

Sources for this entry:

Fair, Susan W. Alaska Native Art: Tradition, Innovation, Continuity. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2006.

Graburn, Nelson H. H., Molly Lee, and Jean-Loup Rousselot. Catalogue Raisonné of the Alaska Commercial Company Collection. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996

Himmelheber, Hans. Eskimo Artists. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1993.

Hoffman, Walter James. The Graphic Art of the Eskimos, United States National Museum Annual Report for 1895. Washington, DC: GPO, 1897

Phebus, George, Jr. Alaskan Eskimo Life in the 1890s As Sketched by Native Artists. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1995.

Ray, Dorothy Jean. “Alaskan Eskimo Arts and Crafts.” The Beaver (Autumn 1967): 80-91.

—– Eskimo Art: Tradition and Innovation in North Alaska. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977.

—–“The History of Alaskan Eskimo Art in Ivory.” In Dinah Larsen and Terry Dickey, eds., Setting it Free: An Exhibition of Modern Alaskan Eskimo Ivory Carving. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Museum, 1982: 9-36.

—– A Legacy of Arctic Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1996.

—–“Happy Jack and Guy Kakarook: Their Art and their Heritage,” in Suzi Jones, Eskimo Drawings (Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003: 16-33.

VanStone, James W. “The Bruce Collection of Eskimo Material Culture from Port Clarence, Alaska.” Fieldiana Anthropology 67. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1976: 1-117.

Endnotes:

[1] The drill bow was an essential tool in the ivory engraving process prior to the adoption of metal tools through colonial trade, but Elizabeth Hutchinson has pointed out that the elaborate decoration of these drill bows suggests those most heavily engraved were likely prestige objects rather than functioning tools. Conversation with the author, April 30th, 2015.

[2] See also Nelson H. H. Graburn and Molly Lee, Commerce and Curios: The Alaska Commercial Company, 1868-1904 (Berkeley: Lowie Museum of Anthropology, 1986). It is worth nothing that the Alaska Commercial Company played a pivotal role in establishing government education programs in Alaska. In 1884, when the U.S. Board of Education began contracting with missions of the Presbyterian and others established churches to run schools throughout Alaska, the Company furnished missionaries and teachers with free transportation to and from the north.

[3] Ray suggests it is the gold-rush customers in particular who discover the Inupiaq talent for copying, but as the work of Happy Jack and Guy Kakarook will show, these talents became apparent much earlier than the Nome gold-rush. See Ray 1977, 43.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.