by: Sophie Adelman & Yuxing Zhang

Wooden Fangzhang Map

Recipe: 予奉使按边,始为木图,写其山川道路。其初遍履山川,旋以面糊、木屑写其形势于木案上。未几寒冻,木屑不可为,又熔蜡为之。皆欲其轻,易赍故也。至官所,则以木刻上之。上召辅臣同观。乃诏边州皆为木图,藏于内府。(Source: Brush Talks from Dream Book, Shen Kua)

Section II describes an object (木质地图/木方丈图) mapping a terrestrial space—a map on wooden plates made by Xie Zhuang (谢庄), who was a minister during the southern dynasties (AD 730-805). This mapping reconfiguration developed by Xie demonstrates resemblance to the contemporary three-dimensional mapping devices. The final product has a unique shape and consisted of several wooden plates. I intend to create a “Wooden Fangzhang Map” demonstrating the buildings and terrestrial space of the Columbia Morningside campus, following the procedures illustrated by Shen Kua.

Date: 3/8

People Involved: Myself

Location: 110th – 125th along Broadway

Environmental Conditions: Cold! Enough to make my hands pink and numb for a bit. Damp because of yesterday’s snowstorm and the snow dripping down from the top of buildings and scaffoldings because it was melting. It actually got on my paper a little bit, which you can see if you look at my drawing.

Time and duration of experiments: A little over one hour total.

I had put my phone in my backpack so as not to be distracted by it, which ultimately means I don’t know which side I spend more time measuring. It definitely felt like I spent more time walking from 110th to 125th as opposed to the other way around, because there were more breaks in the avenue for side streets on that side (east).

Equipment and tools used: White printer paper, blue pen, my binder as a clipboard, good walking shoes.

Materials and their source and quantities: Nothing really different than what I mentioned before, I guess the street itself was a material!

Subjective factors, e.g., how things smelled/tasted/looked/felt: As I said, the weather was cold and clammy. I think this might have affected the amount of time I wanted to spend outside. I noticed that the air felt brisk on my face, the sky was dim—I really like days like this (though I wish it would’ve been a little warmer) and so I was pleased. My only problem was that it was so windy, I thought it would’ve affected the paper I was using to draw on, and my fingers were so cold along the way. I will discuss the way things looked later in the reflection on this practice, but for now, I think the look of the physical buildings and elements along the way were heightened as I was paying more attention to those, when I usually pay attention the people around me instead.

Prior knowledge that you have: As I walk this path many times to get to Knox Hall for a class, or to the Columbia Gates on most schooldays, I knew the general trend of inclines and declines along Broadway. I knew where to go and that was pretty easy. I knew what I wanted to do which was measure the topography.

Reflection on your practice

I really enjoyed this activity. I noticed that I got a better feel for the land by walking along it, treading it, experiencing its contours for myself and for my own ends. Having a particular goal in mind was really helpful for pushing myself along.

I learned that I didn’t have to have a previous idea of how exactly to measure the topography because I made it up as I went along, which proved slightly less difficult than I expected. I didn’t know that I was going to walk the full way, along both sides of the street, and as I walked it got easier. I stood at 110th and Broadway right as I started not knowing what I was getting myself into and it was a little daunting—in fact, I had put off doing this for a while simply because I didn’t know how I wanted to do the experiment. But as I walked, it got easier, kind of like starting a book that you don’t really know and giving things time, and giving yourself a chance to ease into something. It was a really relaxing practice. I felt at peace with myself and the world around me, I felt more fulfilled, lots of memories of walking the way the path led were rehashed in this practice. It was an exercise in self-reliance, certainly, as I didn’t know who to ask, and this was my responsibility/duty, so I felt inclined to take risks and experiment new ways of thinking about my map and new ways to observe the world around me.

Having said this, I did think the way that I was measuring was pretty arbitrary—as there was no one telling me how to do my experiment, I could’ve been doing it all wrong. But this does make me think that there’s no wrong way to do an experiment that’s being recreated and resurfaced by a new actor such as Yolanda and I—I wonder what her experiment is going to look like, and how our measurements varied!)

I noticed that it was easy to get distracted by the people on the street/they were looking back at me as well. I don’t think this is uncommon—there are so many people in this part of town and it’s easy to enter into their bubbles just by looking for so long, but it’s important to remember not to preoccupy myself with other people I don’t know (to be honest, this is something I am trying to work on outside of this experiment).

I didn’t have the patience at first to go all the way back up Broadway on the other side of the street, but I’m really glad I did end up going up the other side. I learned so much else about the street’s layout. It was retracing my steps, just a little, and was another trial just to validate my primary measurements.

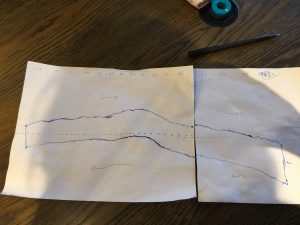

This is strictly an altitude of the two sides of Broadway. My starting point was the east side of 110th and Broadway and I layered the two sheets together to make a complete map.

Questions that arise:

Today, actually, some really pressing historical, mathematical/unit based, and sociological questions arose on my adventure. They are as follows:

What purpose does topography serve if the borders are already prescribed? Can things be mapped out more than once and still have the same exact measurements? I noticed this in walking down Broadway and thought that it was unlikely. It is unlikely that Xie Zhuang and his contemporaries perfectly matched the definitions that an emperor would have claimed as his own land.

Can things really be concisely measured? There seems no perfect boundary for any map or object, this reminds me of when a teacher once told me that a device can never be 100% efficient.

Do people in power allow for borders to shift over time as in line with the Earth’s movements or certain geographical shifts in territory? What about mistakes, how did they react to variances in measurements?

Further, what type of units did the early topographers use to measure their findings? What was the range of accuracy in their findings?

I wondered if my experience would have been different if I looked another way. Would my findings be altered if certain labels were ascribed to me as I walked? I can’t remember which reading this was, but I really considered how much my current appearance is embedded in my research, in the everyday engagements I have with the world around me, and how that effects the way that I perceive the world. How would other people do the experiment differently if they didn’t have the same features, or socialization as I did?